The Story of Victor Valley

Before the White Man: 50,000 years B.P-1840

The lower half of the

Mojave River Watershed

was once filled with a placid fresh

water lake called

Manix Lake. Fed from glacial springs

and rivers in the

San Bernardino Mountains, the lake covered hundreds of

square miles and the green forests surrounding it meant life to prehistoric game

and birds. And for 50,000 years, until the last great Ice Age glacier dwindled

away to the north, it was a haven for Man.

Before the White Man: 50,000 years B.P-1840

The lower half of the

Mojave River Watershed

was once filled with a placid fresh

water lake called

Manix Lake. Fed from glacial springs

and rivers in the

San Bernardino Mountains, the lake covered hundreds of

square miles and the green forests surrounding it meant life to prehistoric game

and birds. And for 50,000 years, until the last great Ice Age glacier dwindled

away to the north, it was a haven for Man.

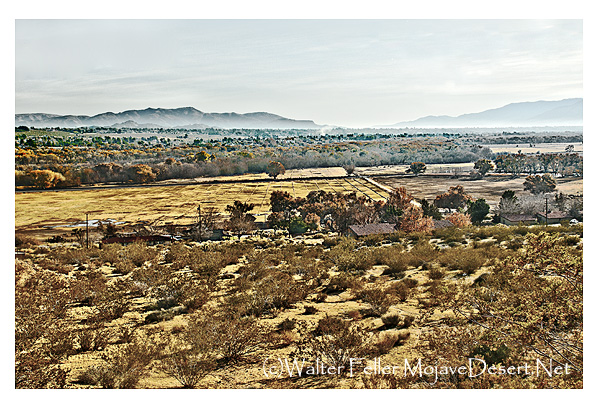

Ancient Lake Manix shoreline

Anthropologists and archeologists theorize that the first wandering Asians, crossing over via the Bering Straits, came this way and in successive migrations moved inland from the sea here, settled along its shores and then spread across North America, becoming the first American Indians. As the Ice Age ended and the climate became harsher, man moved farther away, leaving the shrinking lake to fewer and smaller groups of Indians. Native American legends indicate that a volcanic explosion ruptured a ridge holding the lake and in a single night the waters rushed through a flood widen gorge leaving behind only marshes that fed the Mojave River. The resulting "Grand Canyon of the Mojave", is today called Afton Canyon and is the only "natural" surface drainage leaving Mojave River Watershed.

Afton Canyon

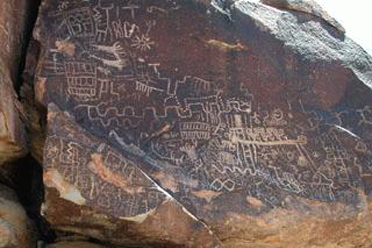

Later, after the strange disappearance of Manix Lake, the fierce Shoshonean Paiutes moved into the area, adapted to it and pushed out the remainder of the earlier inhabitants whose only memorials are a few primitive tools and weapons found near ancient campsites, and mysterious petroglyphs carved into desert boulders and cliffs. The Paiute's themselves later became victims of the desert: limited in numbers and body size because of the dwindling game and food supplies, forced to wander in small groups from water hole to water hole, they had little defense against the marauding parties of Mohave coming west from the Colorado River and slave-hunting Apaches from the southwest.

The Serrano who lived in the forested mountains, the Vanyume along the Mojave River, the Chemehuevi who lived between them and all of their enemies in turn would be displaced by another race of men who first marched into the great Mojave Desert in 1542.

Only fifty years after Columbus landed in the New World, a scouting party of Spaniards attached to the Coronado expedition crossed the Colorado River. After four days in the desert they returned to report the sighting of snow-clad ranges in the West ... the same mountains once crossed by prehistoric man to reach the great lake that disappeared in the night. On September 28, in the same year, Juan Rodriguez Cabrillo stepped ashore on the far side of those mountains to claim all of California for their Catholic Majesties, the rulers of Spain, the West Indies, and most of the Western Hemisphere.

Cajon Pass

Life in the vast Mojave Desert remained little changed for another 230 years. Except for the industrious traders of the Mohave Indian tribes along the Colorado River and nomadic Northern Piaute and Ute, the area was unknown, and unexplored by outsiders. Within three years after the founding of Mission San Diego by Fra Junipero Serra and Gaspar de Portola in 1769, the first Spanish probe across Cajon Pass from the coast arrived, led by Lt. Pedro Fages. Military commander and Governor General of New Spain's remotest province, he proceeded along the northern flank of a mountain range (modern Phelan) across to a valley covered in a thick forest of tall, forked Yucca inhabited by antelope and elk on his way to California's large central valley in search of runaways from Mission San Gabriel, founded the year prior and destined to become richest of the self-sustaining religious communities.

Fages' discovery of a low but steep pass at the end of a box canyon (in Spanish called a "canun cajon" and a marshy tule lined valley on the western headwaters of a northward flowing river, was important to the success of the mission system. During this period of Spanish influence, the missions were still dependent for many of their supplies from beyond the borders of Alta California. The following year Juan Bautista de Anza opened the Santa Fe Trail across the desert from the earlier missions of Arizona and Sonora, and in 1776, Fra Francisco Garces led a party up the Colorado to a tall rocky " needle-like" outcrop and thence across the desert to the headwaters of a northward flowing river.

The Needles

Fra Francisco Garces' westward travels took him to a low "pass" between two mountain ranges near the headwaters of a river that flowed out into the desert. It was here that Garces baptized the watershed's first Christians from the Vanyume and Serrano tribes that lived near the river's eastern and western forks. Later, returning from the "great central valley" to the southwest, Fra Graces retraced his earlier route eastward about 40 miles below the "lower narrows" of the desert river, following a Mojave Indian trading route treading together a handful of desert oases. The existence of water in the river, either running on the surface or lying just underground, had made this a natural route for Indians over the centuries. The happy coincidence of the location of a Cajon pass near its sources contributed to the importance of this trail.

As life became easier at the missions, the handfuls of soldiers quartered there found time to explore further in the new lands surrounding them, locating other Indian bands for conversion by the padres and as always, searching for gold. Evidence of Spanish mining activities dating from this period has been found in the Lucerne Valley to the East, and Arrastre Canyon takes its name from a Spanish ore crusher found there. That they were limited to minor operations may be attributable to the ferocity of the Mojave and other Indians of the desert. Although pack trains with supplies for the missions of Alta California traveled the desert annually, they and any smaller parties were subject to harassment by these tribes. Between the major Spanish settlements of Northern Mexico and Arizona... Caborca, Alamos and Tubac... stood tribal lands of the Apache, Pima, Yuma, and Mojave.

The latter were especially troublesome, being responsible for the deaths in 1819 of seven neophytes sent to establish an asistancia, or branch mission, by the padres of San Gabriel along the headwaters of the Mojave River. After Mexico achieved independence in 1821 restrictions on trade between provinces were eased, and a new track across the desert between Santa Fe, New Mexico and California, the "Spanish Trail" was routed far north into Utah to avoid this menace.

From 1830 on, a pack train of as many as 3,000 mules left Santa Fe with trade goods for the missions, pueblos, presidios and ranchos each year. After wintering in California, the traders returned with prized California horses and mules over the same route. They were not the only herds driven across the Cajon Pass and through the high desert, however. Thousands more were the booty of history's greatest horse thieves: Walkara, "Hawk of the Mountains," of the Ute Indians and his friend Thomas "Pegleg" Smith.

Throughout the Spanish Mission era (1769-1821), the years of Mexican- Californiano rule (1821-1846), and well into the American period, Indians seemed to fall into one of three categories. They were docile, Christianized workers about the great missions; somewhat less docile pagans living away from the white man; and there were the raiders from across the Sierra Madres.

Even before the Europeans arrived, their neighbors the Mojave, and their cousins, the Northern Paiute and Ute, frequently victimized the Vanyume and Chemehueve. Mojave returning from trading trips among the coastal Chumash and Gabrielino stole their women and children. Paiutes coming to winter along the Mojave stole their food stores as well as their women. Then the white man came and brought with him something infinitely better to steal than roots, acorns, rabbits or wives: he brought the horse.

Although they arrived in California with only a few hundred head, mostly mules, the diligent Franciscans possessed herds of cattle, sheep and horses numbering in excess of 300,000 before these were turned over to their ranchero parishioners in 1834. The missions closest to the southern exit of Cajon Pass alone ran over 60,000 cattle and close to 5,000 head of fine horses. Being neither herdsmen nor planters, the Indians could regard that much beef with equanimity. But all those horses represented wealth to hunters and warriors, just as gold did to the white man.

Forays against mission herds began nearly as soon as they were established. But the biggest and best organized were those led by Walkara and "Peg-leg" Smith. Smith, at various times a river-boater, trapper and squawmen, was in the second group of Americans to cross the desert into California. Returning to the Ute living near St. George, Utah, he and Walkara organized and led their first successful raid in 1828, stealing 400 horses and mules from San Gabriel. Hotly pursued across Cajon Pass and high desert by the Californiano, they escaped after ambushing their pursuers at northeast of Lucerne. After 20 years of similarly profitable round-ups, they gathered up over 5,000 prized mounts from all over the area in 1848 in a single coordinated sweep. Witnesses saw the dust cloud rose over Cajon Pass from 30 miles away, but the renegades escaped once again to sell and trade their stolen herds as far away as Texas, Wyoming and Colorado. Smith reportedly retired from the horse-raiding business after this, however Walkara continued to race purloined ponies North across the head of the Mojave until his death in 1855.

Wild mustangs, descendents of strays from these raids, populated the Apple Valley area until the last were gunned down from low-flying airplanes in 1948, exactly 100 years after the greatest horse theft the West had ever seen. In March of 1866, after U.S. Army units had been withdrawn from the desert, Paiute raiders swept up the Mojave River bent on driving off the Mormon ranchers sited at convenient intervals along the trail to Salt Lake City. Captives taken at the Verde Ranch near Victorville were carried along to watch the destruction of the Las Flores Ranch by the savages and were then put to death. The following January the Paiutes returned, driving beyond the Valley into the San Bernardino Mountains near present-day Crestline. Attacking Mormonoperated sawmills, they killed and wounded a number of men working there and retreated with their own casualties in the direction of Rabbit Springs. A posse of 400 from San Bernardino pursued and fought it out with the Paiutes, a band of Chemehueve allies, and the Chemehueve women, children and oldsters, killing nearly all at Chimney Rock.

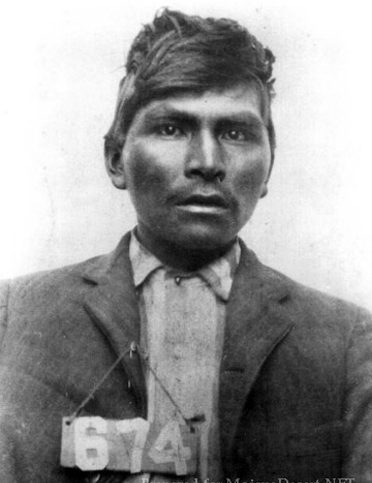

The pioneer SAN BERNARDINO GUARDIAN reported another party of "nearly a hundred" Chemehueve, Cohuilla, Mojave and Paiutes pursued and attacked by a company of 19 "Rangers" in the same area the following month. After three days, the Indians retired, leaving four dead and two Rangers wounded. Thereafter, Indian incursions into the territory dominated by the white man were limited and relatively peaceful. The last, tragic clash between Paiute and the white man's law came in September of 1909 with the widely heralded manhunt for "Willie Boy." A 29-year-old Victorville resident, "Willie Boy" was sought for the murder of another Indian at Banning, and kidnapping of the man's daughter. Tracked into the mountains, the last Paiute woman-stealer died of his wounds, alone, after several days of running.

A new people now owned the desert; the water holes and the trails were heavy with their traffic.

< index - next >

The Story of Victor Valley

Westward Expansion

The Road Builders

Homesteaders & Hucksters

Last Stop at the Bottom

Starting Again

Bright Promise

Grapevine Canyon - Colorado River

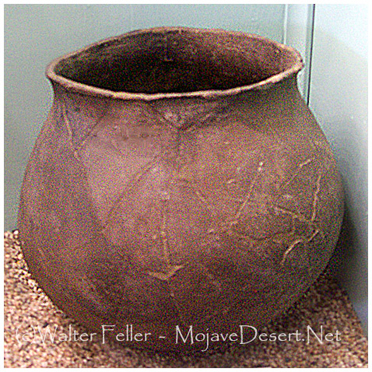

Vanyume cooking pot

Mission San Gabriel

Chimney Rock

Willie Boy