Introduction

“Born of a face perceived, but never fully seen.”

The Mojave Desert: A Unique and Vital Ecosystem The Mojave Desert, spanning parts of California, Nevada, Arizona, and Utah, is a unique and vital ecosystem characterized by its extreme climate, diverse flora and fauna, and rich historical significance. Covering approximately 47,877 square miles, it is known for its iconic Joshua trees, stark landscapes, and vibrant biodiversity.

Geographically, the Mojave Desert is bounded by the Sierra Nevada to the west, the Colorado Plateau to the east, the Great Basin to the north, and the Sonoran Desert to the south. It features a variety of landforms, including rugged mountains, expansive valleys, and dry lake beds. The climate is typically arid, with scorching summers and cold winters. Precipitation is sparse, often less than five inches annually, resulting in a harsh environment where only the most adaptable species thrive.

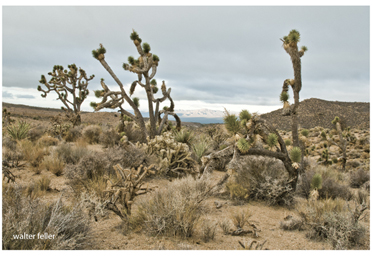

Despite these challenging conditions, the Mojave Desert hosts a remarkable array of life. The Joshua tree, a symbol of the desert, dominates much of the landscape. Other notable plant species include creosote bush, cholla cactus, and various wildflowers that bloom briefly in the spring. The desert is also home to diverse wildlife, such as the desert tortoise, Mojave rattlesnake, and various bird species like the roadrunner and the burrowing owl.

The human history of the Mojave Desert is equally rich. Indigenous peoples, including the Mojave, Chemehuevi, and Paiute tribes, have lived in the region for thousands of years, developing a deep understanding of its resources and seasonal rhythms. European explorers and settlers arrived in the 18th and 19th centuries, attracted by opportunities for mining, railroads, and military installations. These activities left a lasting impact on the landscape and its ecosystems.

Today, the Mojave Desert faces significant conservation challenges. Urban sprawl, resource extraction, and climate change threaten its delicate balance. Efforts to preserve this unique environment include protected areas such as the Mojave National Preserve and Joshua Tree National Park. Conservationists work tirelessly to mitigate the impacts of human activity, ensuring that the Mojave Desert remains a haven for its unique species and a testament to nature's resilience.

In conclusion, the Mojave Desert is a place of stark beauty and profound ecological importance. Its extreme climate and diverse life forms create a unique ecosystem that is both fragile and resilient. Understanding and preserving this remarkable desert is crucial for future generations to appreciate its natural and historical significance.

Overview

Great Basin Desert

Mojave Desert

Sonoran (Colorado) Desert

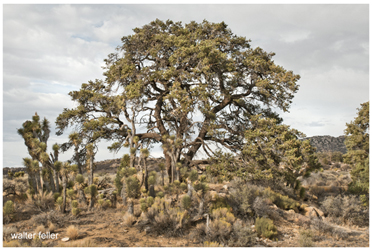

Pinon pine acts as nurse to Joshua trees

El Mirage Dry Lakebed

Desert perennials