Human Settlement: Early Peoples of the Mojave Desert

Recently, Mojave Desert

petroglyphs

(rock pictures) have played an important role in debates about the age of the

first human occupation of the New World. New dating results show that Paleoindians may have reached this area as

long as 15,500 years ago. No associated habitation sites have yet been discovered in the Mojave, however, which

suggests that these prehistoric peoples moved from place to place. Over time human settlement patterns became

increasingly organized, with more complex rituals and a subsistence reliant on seeds,

plants,

and farming.

Small-game hunting contributed meat protein to the peoples’ diet.

Several tribal groups have lived in the Mojave Desert within the past 2,000 years. The northern and eastern

portions, for example, were occupied by the

Kawaiisu,

Kitanemuk,

Serrano, and

Koso,

and Southern Paiute bands,

including the

Chemehuevi.

Culturally distinct, these groups nevertheless spoke related languages and had similar

socioeconomic systems. Resource gathering was done in family groups over wide areas, but for at least part of

each year life centered on more permanent villages. The tribes knew much about Mojave Desert resources,

enabling them to gather supplies from all portions of their territories. They generally had friendly relationships

with neighboring groups such as the

Mohave,

though they also experienced episodes of intertribal hostility.

The

Mohave Indians

made pottery from

clay

and crushed

sandstone,

decorating their creations with geometric

designs. The art of tattooing was also important to the Mohave, who frequently adorned their faces 500 km

trips to the Pacific Coast to trade pottery and other goods for seashells and beads. Mohave legend holds

that tribal runners could cover the distance in only a few days, traveling by way of perennial

springs

and the

Mojave River.

The Chemehuevi tribe spoke a different language from that of the Mohave Indians. They occupied a particularly

barren portion of the Mojave Desert and wrested a rough living from the open land. Like their Mojave neighbors,

the Chemehuevi were highly mobile, making use of resources throughout their large territory; however, they also

had settlements to which they returned regularly. To transport goods and for other purposes, they created complex,

beautiful baskets from reeds and grasses. Like other Southern Paiute groups, they sometimes worked small farms.

Fortune hunters were the first outsiders to venture into the Mojave Desert, at a time when the Mohave Indians

were the largest concentration of people in the Southwest. But it wasn’t until 1775 that

Francisco Garcés,

a Spanish Catholic missionary, became the first European to meet the Mohave Indians, who accompanied Garcés on

his journey to the coast. Garcés’s route, which also took him through Chemehuevi lands and was documented in

great detail in his diary, became known to later travelers as the

Mojave Road.

American “mountain men,” led by the legendary

Jedediah Smith,

appeared in Mohave Indian territory in 1826, and

though tribe members first welcomed the trappers, conflict was not long in coming.

In 1827, another trapping party came through Mojave land, ignoring the tribe’s requests for goods in exchange

for trapped animals. The resultant conflict left victims on both sides. When Smith returned later that year, his

party was also attacked, and for the next 20 years violence reigned, reaching a peak when trappers from the Hudson

Bay Company killed 26 Mojaves.

In 1850, southwestern territory was annexed by the U.S. Army, the beginning of military encroachment on the region.

New transportation routes were critical to an expanding nation, and a wagon trail was opened. In 1858, the first

wagon train en route to California was attacked when it lingered at the

Colorado River

crossing near present-day

Needles.

Spurred by public outcry, Indian fighters were sent to the area from San Francisco. Though there was no

combat and the Mohave claimed no responsibility for the wagon attack, prominent tribe members were jailed and the

army established Ft. Mojave at the crossing. When several Mohaves escaped from prison, soldiers hunted them and

others, eventually banishing the tribe from its homelands near the river crossing.

In 1865, the U.S. Government created the Colorado River Indian Reservation near Parker, Arizona, an area of

poor farmland. Favoring peace, the new Mojave chief guided hundreds to the reservation, while the former chief

remained to lead those who refused to leave their homeland; the tribe was effectively split into two. A compulsory

education law for Indians was passed, partly to eradicate native language and culture. The Mojaves were taught

American farming methods, though they had no railroads for work, others labored on riverboats, and some sold

crafts to tourists. During this same period the remaining Chemehuevi were forced onto reservations in California.

Traditional Mohave tribal leadership was changed forever in 1957, with the creation of a seven-member tribal

council. The Mojave Desert’s current resident populations of Mojave and Chemehuevi Indians, collectively

numbering less than 2,000, live on reservations in California, Nevada, and Arizona. Today many local tribes

are united as the Colorado River Indian Tribes and the Colorado River Native Nations Alliance.

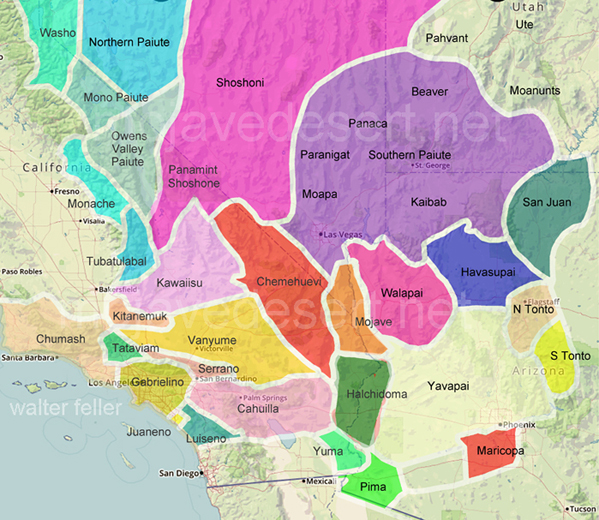

Historic Indian Territories Map

Bighorn sheep are a recurring theme

Mohave Maze

Complex design may indicate older cultures

Obsidian flakes from tool making

Rock used to sharpen awls used in basket making

Pictograph

Communal grinding stone