Rock Trek in the Cadys

An Adventure with Mary Beal - Desert Magazine, December 1948When Mary Beal and Harold Weight went rockhunting into the Cady mountains, east of Barstow, they found agate which will please the collector. And—since Mary is a botanist first and a rockhound second— there were other interesting things along the trail. Here is a report on an area which will prove increasingly popular with the rockhounds and the story of a woman who has labored ceaselessly to perfect her knowledge of the desert flowers.

By HAROLD O. WEIGHT

IF you should come upon a small active woman in some isolated corner of the Mojave, wrapped about with photographic equipment and clinging to the canyon wall with fingers and toes while she decides whether to study a flower or investigate a mineral specimen, it will be quite safe to say: "Hello, Mary Beal."

Of course if it is Mary Beal on one of her botanizing expeditions, the flower probably will get the preference, for she is a recognized authority on the flora of the desert. She knows flowers because she loves them.

She also is interested in rocks and was hunting specimens in the Calico mountains more than 30 years ago when one used a horse and buggy to visit the ghost mining camp. Rocks are piled all over the place at her small cabin on the Dix Van Dyke ranch near Daggett.

Mary had not been forewarned early last June when I drove from the bright Mojave glare into her tree-shadowed oasis to suggest a field trip to the Cady mountains. But she nodded and said, "When do we start?" And we started. Nominally we were after rocks, but Mary feels that any excuse for a trip into the desert outlands is valid, and rockhunting and botanizing fit nicely together.

The Cadys lie about 40 miles east of Daggett—an oddly shaped series of mountains, buttes and valleys which stretch across most of the 25 miles between highways 66 and 91, northwest of Ludlow. They take their name from old Camp Cady, which was established in April, 1860, on the Mojave river at the northwestern tip of the range. Major James H. Carleton probably picked the spot because springs seep from the cliff there. The camp was maintained for protection against Indians who raided the Salt Lake or Old Spanish trail and was abandoned in 1866.

Little geological information has been published about the Cadys. During the two world wars some manganese, barite and celesite were mined along the southern slopes of the range, and there are active claims in that vicinity. It was this southeastern section, composed largely of Tertiary lavas, that we planned to investigate. Many beautiful rock specimens have come from the area, which lies close to Highway 66 and the old road between Ludlow and Crucero. I had hunted in the buttes nearest that dirt road before, and had found excellent material, but not in sufficient quantity to justify a mapped field trip.

It was hot when we reached Ludlow, a railroad town which once was the southern terminus of the Tonopah and Tidewater line. Oleanders bloomed along ther streets, but there was little greenery about the town and signs in the service stations warned: "Do not waste water."

Mary explained: "Water has always been a problem here. Every drop used for any purpose has to be hauled in." There is water under Ludlow—but it is a long way down. When the railroad, then owned by the Southern Pacific, was completed in 1883 a well was drilled to 1600 feet. The drillers struck water at 785 feet and again at 1084 feet. The water was fairly good for boiler or domestic use, according to David G. Thompson in his monumental water supply paper, The Mohave Desert Region, published by the U. S. geological survey. But either the yield was insufficient or it was considered uneconomical to pump from such depth. The well was never used and water was hauled by tank car from Newberry Springs.

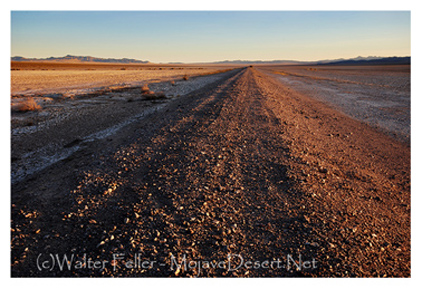

We zeroed the speedometer at Ludlow and left the pavement, taking the bladed road which leads almost due north through Broadwell valley, which separates the Cady and Bristol mountains. At 1.6 miles, we crossed the roadbed of the abandoned Tonopah and Tidewater railroad. Borax Smith built this $3,000,000 narrow-gauge across the blazing Mojave in 1907, to tap his great Lila C. borax mine on the edge of Death Valley. Smith had planned to run a spur from the railroad Senator Clark was constructing from Las Vegas, but when terms could not be arranged, Smith built his own line from the Santa Fe at Ludlow to Beatty. It was a struggle to keep sufficient men on the job through the summer heat, but C. M. Rasor staked the right of way and John Ryan drove the project through.

Today only the roadbed and a few ties, too rotted to salvage, show where borax-loaded trains once puffed their way through now silent desert mountains. This section of the narrow gauge was the first to become superfluous when the Salt Lake railroad— now the Union Pacific—crossed the Tonopah and Tidewater at Crucero and shortened the Death Valley haul by 25 miles.

We reached the edge of Broadwell —sometimes called Ludlow—dry lake at 5.8 miles. Here the road divides, the dry weather route crossing directly through the playa, the wet weather trail angling to the left to keep above the dry lake. We followed the wet weather road to 7.4 miles where an auto trail took off left, into the great sloping bajada which cuts to the heart of the Cadys. These were the sort of tracks which are made only by rockhounds or prospectors and when they headed back southwest toward the red and green volcanic buttes and peaks I hoped to explore, we followed them.

The road was typical of the more primitive type. It twisted and wriggled to avoid rocks and bushes, bounced in and out of drainage ruts and curved up sandy wastes. Near the southeastern end of the Cadys, it entered a broad barranca and headed in the general direction of a large, strikingly banded mountain. The foothills which we were approaching showed strong contrasts of reds, greens and whites. At 10.5 miles, a faint branch headed right, but we followed the main trace up the wash.

We were passing through the typical desert vegetation of the region. There were healthy-looking catsclaws with well-developed seed pots, their green leaves the brightest things in sight. Burroweed, desert holly and creosote bush were plentiful and we came upon increasing numbers of grey and ragged smoke trees. On my way up to Daggett, the great smoke trees in the washes along the Salton and through the Coachella valley were crowded with rich blue blooms. But there seemed neither buds nor flowers on these in the Cadys. The blooming period varies greatly, Mary explained, according to altitude and location.

Then, close beside the sandy auto trail, we saw a large crucifixion thorn bush, its branchlets thick with clusters of nut-like fruits. This called for photographs, and while we set up our equipment, Mary told me that the plant —Holacantha emoryi Gray, a member of the Ailanthus family—has flowers of separate sexes. The stamens grow on one plant, the pistils on another. Holacantha is from the Greek and can be translated as meaning wholly a thorn—which is an excellent description of the plant, as anyone who has been punctured by the hard sharp points of the stiff branches will testify.

According to some authorities the crucifixion is a plant of southern Arizona and northern Sonora which has spread to the hot deserts of eastern California. It is found occasionally on dry plains and in washes on the southern Mojave near Daggett, Ludlow, Amboy and Goffs, and in portions of the Colorado desert. The crucifixion thorn is grey-green. Its leaves have been reduced to scales, and the yellow flowers appear in May. The fruit, reportedly, is popular with burros and goats if they can reach it without having to take the thorny branches.

Mary Beal knew nothing about the desert plants when she first came to the Mojave. In fact, her arrival on the desert was not through choice. Working in the library at Riverside from 1906 to 1910, she met the writer naturalist John Burroughs and a friendship grew between them. She was invited to visit the Burroughs home on the Hudson while on a projected eastern trip during the summer of 1910.

Before the trip was made, Mary was stricken with pneumonia. She wrote to Burroughs, telling him of her struggle to regain health, and he asked her to write to his friend, John Muir. Muir's married daughter lived on a ranch in the desert and Burroughs thought Mary might find refuge there. Muir was sympathetic and in time Helen Muir Funk, who had gone to Daggett under similar circumstances, told Mary to come out. A woman on the ranch could take care of her washing and feed her, but she must bring her own tent to live in.

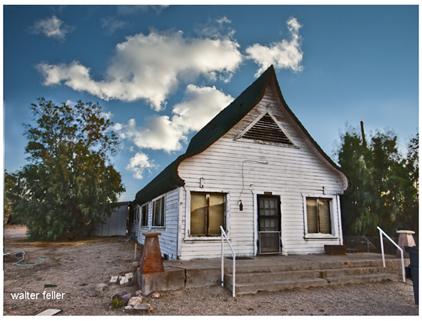

A friend obtained the tent and it was set up, with wooden floor and sidewalls, right where Mary Beal's little home stands today. Mary had been warned that the desert was terrible, but her doctor told her she must stay a year and a half. She came to Daggett determined that she would not be licked by the desolation.

It was a stunning change for one used to cities and softer lands. All trains stopped in Daggett in those days, even the fast train of its day, the California Limited. Mary's friends would let her know when they were traveling. And when she drove in to see them for the short stop, they would have flowers for her and would sympathize with her. But Mary, who had come to the desert only to exist for a year and a half, found that she did not need their sympathy. "They called it a God-forsaken place," she said, "but I came to love it."

And when her period of exile was over and she went back to the doctor he told her: "You can live anywhere in the world you want to now. But I think you will be healthier and live longer if you go back to the desert."

And, strangely enough, Mary found the advice was not hard to take. She went back to the desert—and she went back to stay. The floor of her living room today is the same wooden floor that once was in her tent house. But wooden walls and roof have replaced the canvas. Rooms were added as her belongings and interests increased. Electric lights, refrigeration and piped water have made the mechanics of life easier.

But the greatest change has come through the veritable jungle of trees and shrubs, orchards and vines which have grown up about her home and on the Van Dyke ranch. Mary has pictures of the tent house and its development. When she first came there was one tree near, and she could see the mountains in all directions. "You know the desert mountains," she said. "They have a color and personality all their own—which is hidden by heavy vegetation on other mountains." But today Mary must walk to the edge of the ranch before she can see any of the ranges she knows so well.

Mary kept up her acquaintance with John Burroughs. Once, in 1912, she drove him by buggy to Calico. He was fascinated by the broad geological strokes with which Nature had drawn those colorful mountains. When Mary saw him just before he died he remembered the trip. "I've always wanted to get back to the Calicos," he said. "Now I guess I never will."

John Muir came to the ranch, and of course T. S. Van Dyke was there. John C. Van Dyke, who wrote that classic of the arid lands, The Desert, was a visitor. These men, who loved and expounded the wonders of Nature, whetted Mary's interest in the desert about her. And the wildflowers that bloomed in profusion on all sides reawakened her interest in botany. But there were so many flowers she could not identify—many she could not even find listed.

What she considers her greatest help — Willis Linn Jepson's Flowering Plants of California—was published in the early twenties. Then Mary really went to work. Many a night she spent with botany manual, dictionary, and the flower she was trying to identify. Her only formal botanical training was the high school botany course to which most of us have been exposed. So the dictionary was necessary to translate botanical terms so she would know what the description meant and what to look for.

"But those terms are necessary," she said. "They concentrate the meaning of an entire sentence in a single word."

Mary literally wore out some of her manuals in becoming an authority on desert flowers. As time went on she received the active help of Dr. Jepson in her work. During the flowering seasons, the University of California professor spent days and weeks in the vicinity of Daggett. Mary went on many all day trips, collecting and observing plants with him. And from these sessions she received encouragement to continue her studies alone.

Mary has made hundreds of flower portraits, and today she uses three cameras in her work: a Korona view, an Eastman 3A and a little Zeiss. Most of the closeups are done with the Korona, which once belonged to a Mount Wilson astronomer who used it to photograph Halley's comet. Now it is focused on the flower stars of the wild desert gardens. She makes many pictures in the field, exercising painstaking care to show plants and flowers in their natural setting. But most of her beautiful flower portraits are taken indoors, using the blooms she brings back from desert mountains, valleys and mesas.

She makes the closeups with the natural sunlight which falls into the room. Exposures, with small iris openings and fast film, are around 30 seconds. She has hand colored many of the flower pictures, and lately has been branching into color photography with the Zeiss.

After we had photographed the crucifixion thorn and its fruit, we resumed our trek up the winding desert trail into the Cadys. At 11.5 miles, another wash opened to the left and jeep tracks indicated that someone had been investigating what looked to be excellent rock country. But the main road continued right and at 11.8 miles divided. The left branch went perhaps 100 feet to a much used camp site. The right branch ended at the base of a barren greenish ridge after about .2 of a mile of twists and bumps. There had been a number of camps at the ridge, but the last little stretch is the worst of the entire road and is not advised for any low-slung car.

We halted at the lower camp. Any doubt that we had followed a rockhound road was dissipated when we climbed out of the car. In the wash and on surrounding flats were numerous bits and chunks of agate, chalcedony and moss. The many broken pieces showed the area had been wellhunted, but good rocks still could be found.

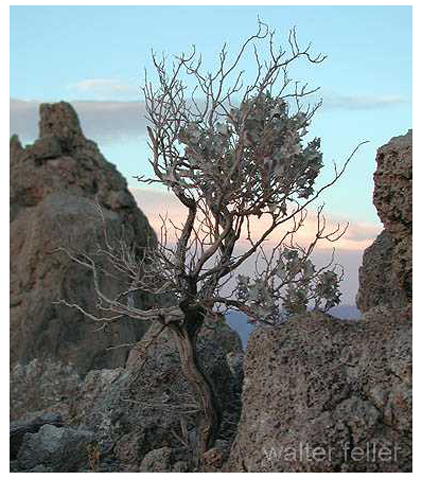

The topography of this section of the Cadys is rugged and treacherous— with steep pitches, crumbly rock and an overlay of insecure volcanic boulders. But it is spectacular and vividly colored and some of the sweeping views into the infinity of the Mojave approach the sublime. Throughout much of the day, while a breeze tempered the summer heat, we climbed over ridges and through canyons. Cutting material was found in many spots —usually in limited amounts. Since the same formations continue for miles, there unquestionably is a great deal of fine agate and chalcedony waiting for the person who is willing to expend time and energy to find it.

The best locality we visited lies about half a mile beyond and to the southwest of the camp site, along the green ridge against which the road ends. The best route lies up a wash which cuts off right just below the road Y mentioned at 11.8 miles. I discovered that while this wash probably can be navigated for some distance by a short wheelbase jeep, it spells trouble for a longer car. After a successful .2 of a mile, clambering over bushes and geeing and hawing at some of the twists, I attempted to ride over an innocent appearing burroweed. I found the bush had a very solid rock center. I was stalled with a boulder too large to be moved thrusting up between my front wheel drive and oil pan.

It was a situation which might have led to a long hike under the summer sun. But I had two old Ford running boards along. So I jacked up first one front wheel and then the other, building a ramp of stone under each. When the ramps were high enough so the front drive would clear the boulder, I placed the running boards as paving on each ramp, under the wheels, and rolled back into the clear without a rasp.

We elected to walk from that point, and a little farther on came to a ledge of red volcanic rock through which the intermittent stream had gouged a narrow channel. The red rock was seamed with calcite, and later investigation of some larger samples taken proved the calcite would fluoresce a strong reddish orange under the ultraviolet lamp.

Beyond the red ledge, the canyon swung sharply left, and a V-shaped drainage channel could be seen cutting down from the ridge on the left. On the slope this channel cuts, and at the head of the channel, is a regular silica "blowout," with agate and chalcedony of almost all grades, from good to bad, plentiful. We found moss of varied colors, small crystal-lined vugs, fortification agate and small amounts of exquisite material which could be classified as plume.

When we had filled our collecting sacks, Mary and I climbed to the top of the little hill and sat on blackened volcanic rocks to rest and absorb the mammoth canvas of the Mojave spread out below. A plump chuckawalla clambered over the edge of the rise. Seeing us, he changed direction and— showing no fear—headed directly toward us. Perhaps a dozen feet away he halted and surveyed us with the intense curiosity which seems a family trait with this lizard. When I moved toward him, he edged into a crevice under a small rock and peered out.

I reached under the rock and took a firm grip on his hide, feeling him puff with air until his loose outer skin was inflated and wedged against the rock. It was impossible to pull him from his refuge until I violated the rules of the game by tipping the rock up, and held him blinking in my hand. He struggled to escape—and his claws were sharp — until a gentle rubbing on the head assured him that my intentions were not unfriendly. Then he relaxed and seemed to enjoy the massage. I transferred him to Mary Beal's hands where, after another period of unrest, he submitted with noticeable lack of enthusiasm to having his picture taken.

I have always considered chuckawallas as slow moving. But when we released this fellow, the speed with which he reached the edge of the hill would have been creditable in a sprinter. At the brink he paused to look back at us, seemed to shake his head doubtfully, then vanished.

We settled back to stare out across the desert—the vast, mountain-strewn Mojave. The Cadys were spread out, and the Bristol mountains, and Broadwell valley and the dry lake. And one could look into the north, along the route of the vanished Tonopah and Tidewater, to Soda Lake mountains and the sandy Devil's Playground. Beyond them even, to the shadowy Kingston range, wavering and dancing in the heat haze.

In all that emptiness we could see nothing that moved. Even the thread of road we had followed into the hills was hidden. With the chuckawalla gone, we seemed utterly alone—and yet there was no loneliness. There is a vast, all-encompassing difference between loneliness and solitude. That is what Mary Beal's friends did not understand. No one who has felt the living peace of the desert can call it "God-forsaken."

Daggett, Ca.

Union Pacific

Tonopah & Tidewater

Cady fault

Cady mountains

Calcite scalenohedron

Fluorite

Desert holly

Mojave aster

Globe mallow

Prickly poppy

Soda Lake/Devil's Playground

Chuckwalla