Rose-Baley Wagon Train 1858

Too impatient to wait for the new road to be completed, two wagon trains of emigrants left Santa Fe in 1858 to try it out, one

headed by L. R. Rose, and following it another led by Gillum Baley. One member of the Baley train, John Udell, who had had

previous experience traveling in the west, opposed the choice of route, but was overruled. The trains' leaders unfortunately hired

as guide a man who had guided both

Whipple's and

Beale's expeditions

and had been found incompetent by both (1994:80).

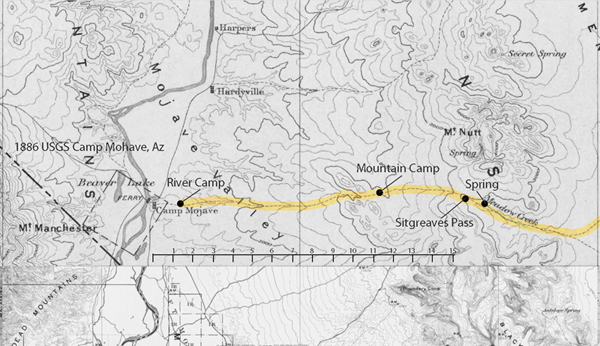

It was late August and the heat was intense. By the time the two wagon trains had reached the summit of

Sitgreaves Pass

in the

Black Mountains, they were exhausted, hungry, and thirsty, and had been harassed for some time by Yavapai and Havasupai in

the Peach Springs area. One small group of them, including L. R. Rose, who wrote the only eyewitness account of the next few

days, pushed onward to the river,

which they could see from the mountain tops. On the way to the river, the party encountered Mojaves,

who seemed friendly, and at first gave the party directions and other help; however, when the wagon train reached the river, set

up camp about a mile from it, and drove the livestock to the river to drink, the Mojaves, who had learned that yet another party

would be coming through, began to kill and drive off cattle, cook and eat them, and "when caught in the act would laugh and treat

the matter as a huge joke" (Rose 1859).

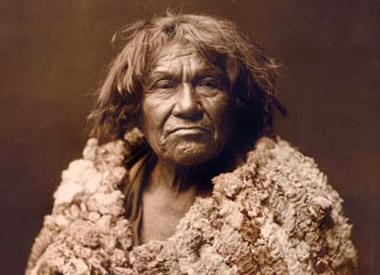

According to Chooksa Homar, the Mojaves had been undecided as to a course of

action. AratÍve,

the high chief of the southern

group of Mojaves, and five "brave men" or sub-chiefs had been involved some years before in a Quechan war with the Cocopa

and the latter's allies. At its end, they promised the commander of Fort Yuma not to fight against other Indians, and were

given written papers confirming their agreement not to. Now that the emigrants had violated their territory, the five sub-chiefs

were tempted to attack them, anticipating that if they allowed the whites to stay in their area, the intruders would take their

wives, enslave their children, and put all the Mojave to work. They had heard that in areas to the east, the whites had taken

over the country, penned up animals rather than letting them run free, and might do the same to the Indians. Tribal elders urged

peace on the grounds that these leaders had the papers showing that they had agreed not to fight, but in the face of the emigrants'

abuse of Mojave hospitality, the militant sub-chiefs decided to defend their territory and their property (Kroeber and Kroeber 1973:11-12).

In 1903, a Mojave known as Jo Nelson, whose Mojave name was Chooksa Homar, narrated to anthropologist A. L. Kroeber through an

interpreter an account of Mojave wars between 1854 and 1880. Kroeber's son, Clifton Kroeber, an ethnohistorian, edited the

manuscript his father had begun, and had it published by the University of California Press in 1973.

In the meantime, on August 27, the Baley party had passed through

Sitgreaves Pass

in its turn and had camped at the edge

of the valley. The young men in the party drove the party's cattle down to the river to drink, intending to return later

for the wagons. When the Rose party moved to the banks of the River on August 29, two Mojave chiefs, probably Cairook

and Sickahot, visited the camps in turn with their retinues. Gifts were exchanged. The chiefs asked if the travelers were

planning to settle on the river, and were told that the emigrants intended to go to California (Rose 1859).

On August 30, the Rose party moved its camp down the river about a mile to the crossing place, noting with pleasure the "grass"

for grazing, and the

cottonwood trees

that would be useful for constructing their camp and building rafts for crossing the river. They

apparently did not realize that the cottonwoods were considered valuable property by the Mojave. The trees provided shade from the

sun, lumber essential for house poles, and material for clothing (the inside of the bark was used for women's clothing). Moreover,

the grass that the emigrants' cattle tramped over and grazed on constituted Mojave fields, which were, of course, not laid out

in rectangles nor surrounded by fences. Many Mojaves began to appear in the vicinity. Because they thus far had been friendly,

the Rose party took no alarm as the afternoon wore on, but in the evening the Mojaves attacked, surrounding the camp, and coming

within 15 feet of the wagons to discharge their arrows. Of the 25 men in the party, one was killed in the battle at the camp,

and 11 were wounded. The Mojaves, subjected to bullets rather than arrows, lost 17 within sight of the emigrant camp, and

possibly more (Sherer 1994:82-85, Rose 1859).

Panic struck the emigrants. Added to their distress over the results of the battle, was the fact that in the midst of their

own battle, Rose got word that Miss Bentner, a member of a family from his party who had stayed in the mountains, had been killed.

The emigrants had lost all but 17 of 400 head of cattle, and all but 10 of 37 horses in the battle by the river. They also retained

two mules, but they had lost their equipment and supplies, and they feared that all their friends left in the mountains had been

killed. Despite the fact that

San Bernardino

was only 200 miles away and Albuquerque, 560 miles, they decided to turn

back (Sherer 1994:85). Fortunately, the Baley party had not been killed and turned back with them, and they met two other westbound

parties following behind who also turned back and shared supplies with them. Before the combined parties reached Albuquerque, they

were in a destitute state, but managed to get word to Major Backus, in command of the

U.S. Army

post there, who sent them sufficient

food and supplies that they were able to reach the city (Sherer 1994:85-86).

All four members of the Bentner family been killed by Walapais, among whom were seven renegade Mojaves. The murder of this family was

interpreted as a massacre, and news of it touched off a round of misunderstanding that resulted in the establishment of

Fort Mojave

and the

U.S. military control of the Mojave

(1994:86).

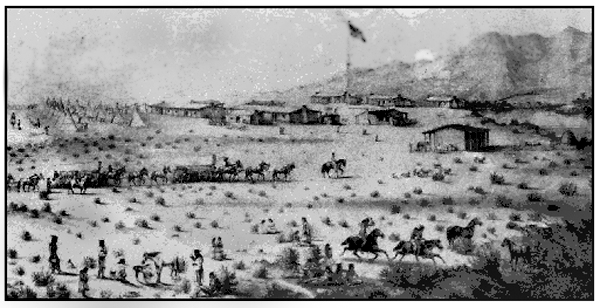

Fort Mojave

News of these events in late August, 1858, spread across the continent, first as exaggerated rumor, later in published versions. The

eyewitness account written by L. J. Rose on October 28, 1858, was published by the Missouri Republican on November 29, 1859, more

than a year later. 7 Colonel Bonneville, the officer in charge of the U.S. Army's Department in New Mexico reported to the General

of the Army in Washington, and probably sent word to General N. S. Clarke, commander of the Military Department in San Francisco. General Clarke

reacted promptly by sending

Lieutenant Colonel William Hoffman

and an escort to the

Colorado River

to arrange for a military post at

"Beale's Crossing" to protect emigrants as they came through. Troops were to follow. The Secretary of War's instructions to do much

the same thing arrived after Hoffman was already well into the desert, and did not reach Hoffman until after he had had a decidedly

unfriendly encounter with the northern group of Mojaves at Beaver Lake. Each side was suspicious of the other, and each expressed

the suspicion in a characteristic manner, but misinterpreted the actions of the other. For example, Hoffman's party, although its

members interacted with the

Paiutes

and

Mojaves

they met in the daytime, declared their camp closed to more than 15 at a time, and

to all Indians at night-an indication of hostility to the Mojaves, to whom open hospitality was only polite. The Mojaves in turn shot

four arrows into Hoffman's camp, mocked the behavior of the strangers, and otherwise tested the intentions of the visitors. In the

end, Hoffman made preparations to return the way he had come, but had not left when his party was surrounded by Mojaves coming closer

and closer. He sent the pack and wagon ahead and then ordered one of his platoons to dismount and fire at the Indians. He reported

that 10 or 12 were seen to fall. Then, as he and the platoon marched to catch up with the rest of their party, some 250 to 300 Mojaves

started to follow, but fell back after "a few well-directed shots on some scattering ones" (Sherer 1994:87-94). Chooksa Homar reported

that three Mojaves were hit, but none killed. A. L. Kroeber noted that to the Indians, Hoffman's visit seemed unmotivated (Kroeber and Kroeber 1973:20).

John Udell, who was a member of the expedition who had not gone down to the

river, wrote an account of it in his journal (1859), but

it was not published until considerably later.