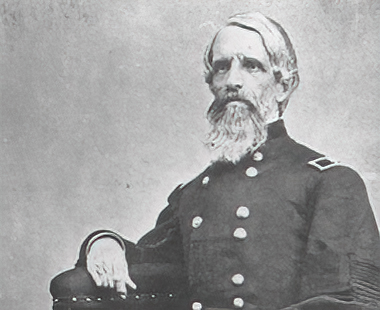

Hoffman Establishes Fort Mojave

Hoffman

reported that the route he had taken across the Mojave Desert was too difficult to send troops through in larger

numbers. General Clarke followed his advice and sent him to Fort Yuma to organize incoming troops and establish a supply

line, preparatory to establishing a post at the place from which Beale had crossed the Mojave in 1857. Hoffman, whose

report of his encounter at Beaver Lake was interpreted by Clarke as the report of an attack by the Mojaves, was given

orders in accord with this view. He was to march against the Mojaves and

Chemehuevis,

and if they declined to engage in

combat, to demand the chiefs who had made the attack on his party and take them hostage. If the hostages were not

forthcoming, Mojave fields were to be laid waste, and further cultivation of the fields denied them (Sherer 1994:93-94).

In the spring of 1859, while Hoffman was still trying to establish a fort at Beale's Crossing,

Beale

was assembling

a road-working party in Albuquerque to build the road he had laid out on his earlier trip. It seemed advisable to send

some of the food and supplies they needed from Los Angeles. After due consideration, Beale's associate, Samuel A. Bishop,

left Los Angeles on March 1 with 38 men,

"ten camels,

six 6-mule wagons, and a number of pack mules." At Cave Canyon in

the Mojave Desert, they were joined by a "mail party" of the Central Overland Mail Company. This enlarged group was met

by an estimated 1,500 Mojave, assembled by the five militant chiefs against the advice of

AratÍve,

which shot at the

whites in such a way as to purposefully miss hitting them. Both sides then retreated, but the five militant chiefs and

some others eventually attacked the intruders, who shot two of them, one of them fatally (Kroeber and Kroeber 1973:17-19). Bishop

sent most of his party back to

Pah-Ute Creek,

cached some supplies there, sent his wagons and teams "back to civilization," and

pushed on with camels, mules, and some supplies to cross the

Colorado

north of the Mojave villages, and thereby get some

supplies to Beale (Casebier 1975).

Hoffman gave notice to the Quechan that he was establishing a military post among the Mojave, but that no peaceful Indian

would be harmed. Soldiers poured into Fort Yuma, and two steamers Colorado and General Jessup stood ready to carry them up

the river; one command of dragoons marched to the river across the Mojave despite Hoffman's opinion that the trip was too

difficult by that route. When these troops arrived together at Beale's Crossing, Hoffman was able to establish a post

there without any opposition from the Mojave, who, on April 23, 1859, accepted the terms he had laid down for surrender,

which included there being no opposition to the establishment of roads and posts through and in their country, and travel

free from harassment; one hostage from each of the six Mojave bands; the chief who commanded the attack on Hoffman as

hostage; and three of those who took part in the attack as hostages (Sherer 1994:94-95).

The chief who had commanded the attack was Cairook, who willingly gave himself up as a hostage. The eight other hostages

comprised two sons of chiefs, four brothers of chiefs, and two nephews of chiefs (1994:95-96).

Neither General Clarke nor Colonel Hoffman felt that the new fort would last very long, being situated in such an unfriendly

climate and so far from a source of supplies. In fact, they doubted that there would be many emigrants who would undertake

the difficult journey across the desert that this route entailed. Brevet Major Lewis A. Armistead, who was left in charge of

the new fort, was more optimistic. He thought the fort was in an excellent location, close to sources of wood, water, and grass,

and having the river as a route over which supplies could be sent. He thought the post was misnamed, however, and changed its

name from Camp Colorado to Fort Mojave (1994:99).

The nine hostages held at Fort Yuma found the confinement oppressive, and eventually plotted an escape. In late June 1859, Cairook

agreed to seize and hold the sentinel during a period when they were allowed out of jail for fresh air, allowing the rest to

escape. Cairook and one other were caught and killed, and the rest escaped, but the army never found out that three made their way

back to their people. A mourning ceremony was held for the two who died. Several weeks later, Mojaves stole stock from a mail

station that had been established two miles south of

Fort Mojave,

and attacked it. Mojaves tore up melons planted by the soldiers,

and the soldiers shot a Mojave, one of three who were working in a garden. Major L. A. Armistead, commandant at Fort Mojave,

frustrated at the escape of the hostages and the difficulty of getting the Mojave to engage in battle, was able to precipitate a

battle between about 50 soldiers and hundreds of Indians-the first pitched battle that had been fought. Armistead reported 23 dead

Mojave bodies found on the battlefield, and there were probably more. No soldiers were killed, but three were

wounded (Casebier 1975:98; Kroeber and Kroeber 1973:27-31).

Peace then descended on the Mojave, but their former isolation was brought to an end by the regular supplies that were brought

to

Fort Mojave

on the

Mojave Road

that Beale and others had forged, following in many places the old Mojave trail that had developed

over hundreds of years. Hoffman had been wrong-freight could be economically carried over the road (Casebier 1975:101-106). It

became U.S. government policy to reinforce the power of the Mojave leader, AratÍve (Irataba, Iretaba), who led a faction of the Mojave

who, recognizing the overwhelming power of the United States, were in favor of peaceful relations. There was an opposing faction, led

by traditionalist "strong men," that favored militant opposition to the invading peoples (C. Kroeber 1965; Sherer 1966).

When the Civil War broke out in 1861, Fort Mojave was closed down because the troops were needed elsewhere. The Mojaves were asked

to guard the buildings (Casebier 1975:131).

Beaver Lake Incident

Riding Out the Civil War

The year 1862 was ushered in by floods, Indian raids and further rumors of secessionist activity on the desert, ...

Military and Pioneer Period

Military in the Mojave