Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad

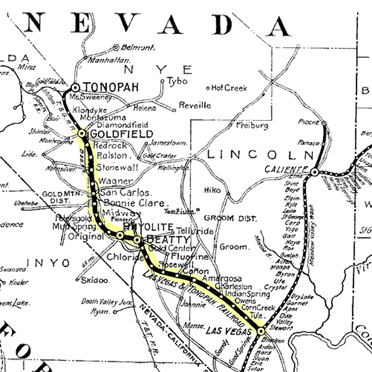

The early twentieth-century mining booms at Tonopah, Goldfield and Rhyolite not only produced major economic and social changes in the life of southern and central Nevada, but also brought about a major restructuring of Nevada's transportation system. As the new camps boomed and prospered, they soon outgrew the capacities of mule teams and freighters to meet their demands, and for the first time railroads were enticed into this region of Nevada. The lure of rich profits from the new camps was the catalyst which brought about the creation of new rail lines, but it was the happy geographic chance that the new camps were situated in a rough north-south line which made a new railroad link through Nevada possible.

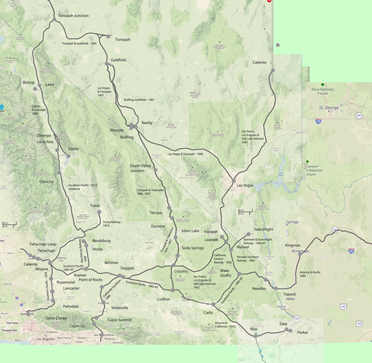

Prior to the boom years, Nevada was served by two east-west lines which passed through the state. In the north, the original Central Pacific Railroad, part of the first continental system, served Reno. Now absorbed by the Southern Pacific, this route had been the main railroad link from Nevada to the rest of the country for several decades. In the south, the recently completed San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad connected the southern part of the state to the west coast and the Rocky Mountain region. Between Reno in the north and Las Vegas, 435 miles to the south, however, there were no rail links. Thus the fortunate chance that the new boom camps of Tonopah, Goldfield and Rhyolite appeared, in succession, in a north-south line between Carson City and Las Vegas made the possibility of the construction of new railroad line connecting those two areas a distinct possibility, the first time.

Such a railroad would cost a great deal of money, though, and the traffic volumes in the early 1900s simply did not warrant the construction of a single line. As a result, the north-south line was connected little by little by a group of independent railroads, built from one camp to another. By the time the Bullfrog boom was well underway, this process had already begun. The Tonopah Railroad Company completed its line from the north into Tonopah in July of 1904, which connected that camp with the Southern Pacific, via the Nevada & California Railway and the Virginia and Truckee Railroad. Within another year, as Tonopah and Goldfield were proven to be solid producers, and Rhyolite appeared to be following their examples, various plans were laid to continue the south-bound connections. The Tonopah Railroad became the Tonopah & Goldfield Railroad in late 1905, and shortly thereafter began construction of a line from Tonopah south to Goldfield. [75]

With the completion of a railroad to Tonopah, which was about half way between Carson City and Las Vegas, the northern half of the connection was completed. In the meantime, several plans for the southern half were beginning to take shape, at least on paper. "Borax" Smith had long contemplated a railroad which would connect his various borax mines in southern Nevada and southeastern California with the outside world, for the days of the famous twenty-mule team borax wagons had long since become economically infeasible. When Senator William Clark completed his San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake Railroad in January of 1905, Smith decided to connect his mines with that railroad at Las Vegas. Verbal agreements between Clark and Smith were reached, and Smith soon announced the formation of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad.

Clark, however, was also looking at the new gold camps to the north of his railroad, and slowly came to the realization that he wanted to build his own line into the interior. The agreements with Smith were thus broken and Clark announced the formation of a rival company, the Las Vegas and Tonopah Railroad. As the names implied, both these southern roads envisioned extending their lines not only to the Bullfrog district, but beyond to Goldfield and Tonopah, thus tapping the potential of all three mining camps.

Clark was the first to set to business. His engineers conducted a preliminary survey from Las Vegas to Tonopah in early 1905 and completed it late in February. The proposed line would run north towards the Bullfrog District, but would bypass the district itself by running through Beatty instead of Rhyolite. The route via Beatty would be comparatively flat and smooth, and would avoid extensive construction costs which would have been necessary to climb the mountains into Rhyolite. After several months of negotiations with Borax Smith, who was forced to shift his operations from Las Vegas on the San Pedro, Los Angeles and Salt Lake line to Ludow, California, where he would connect with the Santa Fe Railroad, construction on both roads began in the fall of 1905.

At about the same time, a third railroad entered the picture when John Brock, of the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad, also spotted the potential of the Bullfrog District, and announced the formation of another railroad company. This one would be a nominal extension of the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad, and would extend those lines south from Goldfield into the Bullfrog District. It soon became obvious to all parties involved, the first railroad to complete its line would have the greatest chance of success, and a race ensued.

In January of 1906, the first rails were laid on the Las Vegas & Tonopah, north of Las Vegas, and a month later the road had been completed for twenty-four miles. Although Rhyolite was ecstatic at the prospect of being connected to three railroads, the town's leaders also realized that the prestige and prosperity of the town would be threatened if rail connections were made at Beatty, four miles to the east, rather than at the metropolis itself. Rhyolite did not want to be on a branch line of any railroad, and began to take steps. After several discussions between the town and the company, an agreement was reached. The Las Vegas & Tonopah agreed to extend its line through Rhyolite, rather than bypassing the city, and the town in turn guaranteed to secure property rights and right of ways through the town. Although this change in plans meant heavy additional construction costs--the Las Vegas & Tonopah estimated that it would cost as much to build a sixteen-mile "high line" through Rhyolite and back out of the Bullfrog Hills to the north as it would to build the entire 115 miles from Las Vegas to Beatty--the town convinced the railroad that the extra expense would pay off. If the railroad ran directly through Rhyolite and the Bullfrog Hills, numerous mines would be able to ship directly on the railroad, rather than having to pay freight expenses to have their ores hauled across the hills to Beatty. Since this meant that more mines would be able to ship their ore, and that more low-grade or could be profitably shipped, the increase in freight profits for the railroad would offset the additional construction costs. Besides that, passenger traffic would be dominated by the railroad which connected directly to Rhyolite, for who wanted to go to Beatty anyway? Despite the fact that the steep grade from Beatty to Rhyolite would mean that the railroad would be forced to stop each train at Beatty and hook on additional engines to negotiate the pass, the railroad was convinced.

The Rhyolite Board of Trade put the matter to a vote of the citizens, who approved the plan. The town announced that it would provide all necessary right of ways and property rights for the railroad if it in turn guaranteed that the route through Rhyolite would be a through route, and not just a branch line. The Las Vegas & Tonopah concurred, and plans were formalized. Doubling the pleasure of Bullfroggers, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad, which had recently incorporated to build south from Goldfield, also announced that its terminus would be in Rhyolite. This road, however, would avoid the hilly route between Beatty and Rhyolite, and would instead build to Beatty, then swing to the south around the hills and hook back to the north, entering Rhyolite from the south.

Construction on the Las Vegas & Tonopah proceeded apace through the early part of 1906. By March, fifty-three miles of track had been laid, and graders were working eighty-four miles north of Las Vegas. To the southeast, "Borax" Smith's Tonopah and Tidewater railroad was inching out of Ludlow, but it appeared that the Las Vegas and Tonopah would win the race to the Bullfrog District. By the middle of June it had finished its grade all the way into Beatty, although the rails were still twenty-nine miles short of that town. The Tonopah and Tidewater had extended its rails seventy-five miles out from Ludlow, but the heat of the summer put a halt to its construction work. In the meantime, the Bullfrog Goldfield had finally started work on its line on May 8th, but initial progress had been slow.

The Las Vegas & Tonopah surveyed and laid out its rail yards at Gold Center, where the trains would be made up, and where northbound trains would pick up extra engines for the climb from Beatty to Rhyolite. Its future grade was surveyed through Rhyolite out to the west around the Bullfrog Hills, then back up to the north towards Mud Summit. This sixteen mile stretch, called the "high line," would constitute the most difficult part of the construction of the entire line between Las Vegas and Goldfield, for after cresting the ridge at Mud Summit, the rest of the sixty-some miles was relatively flat and smooth. The surveying of this line laid to rest recurring rumors that the Las Vegas & Tonopah would stop at Rhyolite and let the Bullfrog Goldfield handle north-bound traffic.

Grading work on the "high line" between Beatty and Rhyolite began during August of 1906, and the rails in the meantime slowly crept up the already completed grade towards. Beatty. On October 7, 1906, the first work train pulled into Gold Center on its completed tracks, and two weeks later the railroad was completed as far as Beatty. Clark had won his race, for he entered the Bullfrog District a full six months ahead of his competitors. Beatty, as usual, held a wild and grand Railroad Day Festival, and all Bullfroggers joined in the celebration, for their town was at last connected with the outside world.

Las Vegas & Tonopah RR

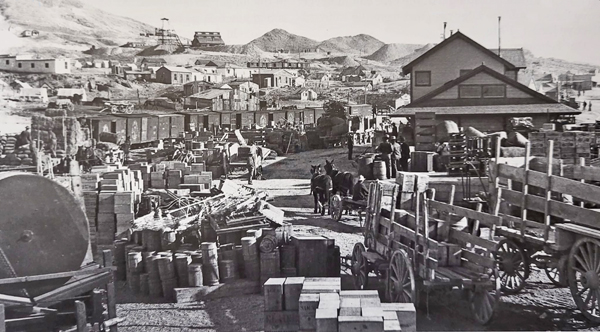

In the middle of November, work on the laying of rails between Beatty and Rhyolite commenced, and on December 14, the first Las Vegas and Tonopah train pulled into the east end of Rhyolite. Freight shipments immediately followed the ceremonial first train, and long awaited carloads of lumber, supplies and mine and mill equipment began to arrive. The completion of the railroad freed the Bullfrog District from the exorbitant freight rates necessitated by long mule-team hauls over the desert, and a veritable building boom got underway, as Rhyolite began to change from a tent city to a more permanent town. Within a week of the arrival of the first train, over one hundred cars stood on the yard tracks in Rhyolite, and more were coming in each day. As soon as the confusion was somewhat cleared, the Las Vegas & Tonopah extended its track through town, before putting a halt to the laying of rails. Further construction, it announced, would await the completion of grading work in the vicinity of Goldfield.

In March of 1907, the first regular Pullman service between Los Angeles and Rhyolite was inaugurated, with daily trains. Grading work around Goldfield progressed, and the town of Rhyolite breathed a sigh of relief as it became evident that it would indeed be on the main line of the railroad, and not be left dangling at the end of a branch line. Then, in April, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad finally finished its line into Beatty. Although the event was not met with nearly the degree of enthusiasm which had heralded the arrival of the Las Vegas & Tonopah, it actually had much more significance, for the north-south rail line through Nevada was now complete. True, it was necessary for passengers to change trains five times between Carson City and Las Vegas, but for the first time it was possible to make the trip in relative comfort and speed.

By the end of May 1907, grading of the Las Vegas & Tonopah line to Goldfield was almost complete, and work began again on the laying of the tracks. During June the railroad slowly extended itself out of Rhyolite, around the Bullfrog Hills, and to the north towards Goldfield. By the middle of August, the rails were completed through the entire Bullfrog District and were extended as far north as Bonnie Claire, a third of the way between Rhyolite and Goldfield. Construction continued despite the financial problems brought about by the Panic of 1907, and on October 26, the ceremonial final spike was driven at Goldfield, marking the completion of the Las Vegas & Tonopah tine. Few citizens, however, were in a mood to celebrate.

Four days later the Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad entered Gold Center from the south, and linked its tracks with those of the Bullfrog Goldfield. Not surprisingly, the two railroads soon announced plans for joint cooperation, and Goldfield and the Bullfrog District were thus served by two complete southern lines. Potential passengers and shippers could travel the Las Vegas. & Tonopah all the way from Goldfield to Las Vegas, where connections to the west coast and the Rocky Mountains were possible, or they could take the Bullfrog Goldfield to Beatty and switch there to the Tonopah & Tidewater for the trip to Ludlow, California, with similar east-west connections at the southern terminus. Although the Las Vegas & Tonopah had been the first railroad to arrive in the district, the Tonopah & Tidewater immediately gained an advantage over its rival, for the latter's connections to, the west coast were quicker and more economical. The Las Vegas & Tonopah countered by advertising that its route went "all the way" and that passengers would be spared the necessity of changing trains in Beatty.

Now, that the race was over, the competing roads settled down to business--hoping that the market for hauling in supplies and equipment and hauling out ore would justify the costs of construction. The Las Vegas & Tonopah concentrated on improvements to its property, including the rail yards at Rhyolite and its passenger station, which was finished in June of 1908. Although events would prove that passenger traffic never warranted the construction of such a large station, the company reaped short-term benefits of publicity for being the owner of what was rightly called one of the showplaces of the southern Nevada desert.

Unfortunately, traffic volumes on all the railroads serving the Bullfrog District proved to be lighter than expected, since the district never became the producer as had been predicted during the early years of the boom. The Las Vegas & Tonopah made a small profit during the first year of operation, but that was the last year that it did. Due to its decision to utilize the "high line" in order to tap the mines of the Bullfrog Hills, the Las Vegas & Tonopah was saddled with heavier operating expenses than were its rivals, since all northbound trains were required to stop at Beatty and add an extra engine in order to negotiate the climb into Rhyolite. The ore from the high line never reached the predicted levels, and thus the railroad was left with the excessive costs of construction, without the ensuing profits from heavy ore shipments.

Miners would use the cars for storage rather than return them to the railroad which would cause traffic backups like this one in Tonopah.

Although both the Bullfrog Goldfield and the Tonopah & Tidewater were experiencing much of the same problems, their shorter and cheaper route to the west coast helped them maintain higher shipping volumes than the Las Vegas & Tonopah was able to manage. In addition, "Borax" Smith had a monopoly upon the shipment of ores from his borax mines along the route of the Tonopah & Tidewater, which helped the revenues of that road considerably. As a final burden, the railroads were burdened with poor public relations. Almost as soon as the railroad days celebrations were over, miners and businessmen began complaining about the high freight rates charged by all the lines. As the mines developed into very low-grade propositions, freight rates announced in previous years began to look like highway robbery. Although the miners had a small point, for the prevalent rates made many mines unprofitable, most of the Bullfrog District mines would have had to be given free shipment of their ores in order to stay in business. Although all the railroads lowered their rates from time to time, no one was ever satisfied. The sentiment that the railroads were making huge profits seemed to predominate from Rhyolite to Tonopah, and as a result, the property of their lines were heavily taxed. The Las Vegas & Tonopah, for example, paid taxes to Nye County amounting to $11,942.70 at the end of 1907. [76]

To make a sad story short, the Bullfrog railroads--and in particular the Las Vegas & Tonopah--declined in direct ratio to the decline of the Bullfrog District. Passenger and freight traffic fell off as mines closed and miners left town. The exodus had a ripple effect, for a smaller population in the district meant that fewer supplies were hauled in to support the remainder. A similar story was affecting the gold camps to the north, for although both Goldfield and Tonopah far out-lived Rhyolite, mines in those northern camps had passed their peak by the 1910s and were beginning what would be a much longer period of decline. In 1911 the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad offered to sell its line to the Las Vegas & Tonopah, thus giving the latter a direct line through most of Nevada. Senator Clark was interested, but following the death of his son on board the Titanic in April of 1912, he turned apathetic towards business affairs, and the matter was dropped.

Matters were now becoming serious, and it became evident that unless the three competing lines were somehow consolidated, that all three would fail. The smallest of the three, the Bullfrog Goldfield, was the first to take action, but its attempt to sell itself to the Tonopah and Goldfield Railroad fell flat. The Las Vegas & Tonopah then stepped in and the two railroads made plans to consolidate their lines. Since both roads had tracks running between Beatty and Goldfield, the decision was made to utilize the best parts of each line, and to abandon the remainder. Accordingly, the Las Vegas & Tonopah tracks would be used from Goldfield to a point just south of Bonnie Claire, where a shift would be made to the Bullfrog Goldfield tracks from there south to Beatty. This move would cut maintenance costs for both lines, and would enable the Las Vegas & Tonopah to avoid running its trains over the costly "high line" from Beatty through the Bullfrog Hills. Through service would run through Beatty, bypassing Rhyolite completely, although that town would still be served by a short branch line. All the track west and north of Rhyolite, however, which includes the section of track which ran through the present boundaries of Death Valley National Monument (Park), was abandoned.

The plans were approved by the Railroad Commission of Nevada, despite the protests of Rhyolite citizens, and the new combined route went into effect in June of 1914. For the first time, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad made a profit--ironically, much of it came from hauling ripped-up tracks and ties from its old roadbed north to Goldfield for salvage. The Las Vegas & Tonopah, however, was not so lucky, and continued to run in the red. Service over the remaining portion of the "high line" from Beatty to Rhyolite was finally discontinued in 1916, and the rails were removed. [77]

As the years slowly passed, revenues and traffic on the Las Vegas & Tonopah continued to decline. Daily service between Las Vegas and Goldfield was maintained until February of 1917, when tri-weekly service was substituted. Then, the problems brought about by World War I spelled the end of the line. Due to war shortages and efforts to economize, the Freight Traffic Committee of the U. S. Railroad Administration ordered that all perishable and merchandise traffic which formerly traveled via the Las Vegas & Tonopah would immediately be shipped only on the shorter Tonopah and Tidewater connections to the west coast. In other words, the Las Vegas & Tonopah was not allowed to haul anything but ore, and there was not much ore to be hauled. For a short while, the railroad was run by the Railroad Administration, but that body soon decided that the Las Vegas & Tonopah was "not considered essential or necessary to the uses of the Government," and was turned loose.

By this time, it was a moot question whether the railroad was essential or necessary to anyone, and the end soon came. The Las Vegas & Tonopah had lost money every year since 1908, but never enough to make it consider abandonment of its lines. Revenues now plunged drastically and the road was faced with bankruptcy. The high prices paid for scrap metal during World War I stimulated Clark to salvage as much of his railroad as he could, and on September 18, 191-8, he applied to the Railroad Commission of Nevada for permission to cease operations. On October 31st, the last train pulled off the line and the tracks were taken up and sold. With the demise of its line, the Las Vegas & Tonopah also abandoned its passenger station in Rhyolite, and one of the last surviving structures in that dying town entered the delinquent tax list. [78]

Following the death of the Las Vegas & Tonopah, the Bullfrog Goldfield Railroad returned to its old partner, the Tonopah & Tidewater, and the two roads combined operations. For all practical purposes, the Tonopah & Tidewater operated the line for the entire distance from Ludlow to Goldfield, for the Bullfrog Goldfield had almost no rolling stock or engines left. Nevertheless, the railroad continued to operate as long as the Goldfield mines operated. As the 1910s gave way to the 1920s, those mines began to close down one after another, and revenues on the Bullfrog Goldfield slowly and surely declined. Finally, in January of 1928, that railroad was also abandoned.

Thus the Tonopah & Tidewater, which had been the last railroad to reach the Bullfrog District, was left as the last and only railroad operating in the vicinity. As the gold mines in the region began to play out, the Tonopah & Tidewater relied more and more upon its borax mines in the vicinity for revenue. Other scattered clay, marble and talc mines contributed enough freight to enable the railroad to operate feebly through the 1910s and the 1920s, and the road became a life line to the scattered population of the southern Nevada desert.

But towards the latter part of the 1920s, the borax mines began to close, and the life of the Tonopah & Tidewater was threatened. The Borax Consolidated Company, the parent of the Tonopah & Tidewater, continued to operate the road at a loss, preserving the rails and stock in case of future need, but heavy losses year after year became too much for it to handle. In 1938, the Tonopah & Tidewater applied for permission to abandon its lines. Local patrons of the road caught the ears of their politicians, and approval of the abandonment was delayed for several years, as means were sought to keep the line operating. But those efforts were ultimately unsuccessful, and on June 14, 1940, the Tonopah & Tidewater ceased operations. The railroad tracks were left in place for two years, in hopes that the railroad could resume, but the need for scrap metal during World War II caused them to be salvaged in 1942 and 1943. The last Bullfrog district railroad had finally died.

The demise of the railroads did not end their influence upon the transportation history of southern Nevada, for during the early days of highway construction in that state, the old roadbed of the Las Vegas & Tonopah was designated as part of the state highway system. When construction of U. S. route 95 between Las Vegas and Carson City began, which was the first major north-south highway through the state, the road was built along the old grade of the Las Vegas & Tonopah from Las Vegas to Beatty. Today, the traveler heading north out of Las Vegas towards Beatty and Carson City will travel along the same line which carried so much hope and optimism during the days of the Bullfrog boom.

The story of the Las Vegas & Tonopah should be interpreted for visitors, in order to introduce to them the role which railroads played in the life and death of early twentieth-century mining camps, and the grade itself should be protected. In itself, the site of an abandoned railroad grade is as startling and as nostalgic a reminder of the dead hopes of bygone eras, when men attempted to wrestle a fortune from the forbidding deserts of southern Nevada, as is the lonely Homestake-King Mill foundations standing guard over a deserted desert.

Death Valley Historic Resource Study

A History of Mining

SECTION IV: INVENTORY OF HISTORIC RESOURCES--THE EAST SIDE

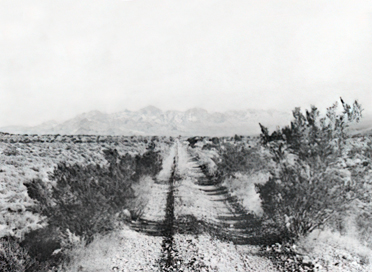

55. Las Vegas & Tonopah railroad grade

56. Las Vegas & Tonopah railroad grade

Illustrations 55-56. Top: Las Vegas & Tonopah Railroad grade, looking west towards the Original Bullfrog Mine from a point approximately one mile east of the Death Valley National Monument boundary line. The dumps of the Original Bullfrog are barely visible in the center background. Bottom: Portions of the railroad grade, looking southeast from the point where the Hometake-Gold Bar wagon road leaves the railroad, about 2 miles northwest of the Original Bullfrog. The grades in these two pictures are clearly marked, as they have been used for many years as auto roads. 1978 photos by John Latschar.

57. Las Vegas & Tonopah railroad grade

58. Las Vegas & Tonopah railroad grade

Illustrations 57-58. Top: A portion of the Las Vegas & Tonopah grade, looking northwest from Currie Well. Notice the fill in the background, and the cut through the small ridge in the background. Bottom: The grade runs straight as an arrow once it leaves the hills and valleys of the Bullfrog district. In this photo, taken two miles north of Currie Well, the road bed may be discerned as it meets the horizon in the background. This portion of the grade is less obvious, since it has not been used as an auto road. 1978 photos by John Latschar.

59. Las Vegas & Tonopah passenger station

Illustrations 59-60. Top and bottom: Front and rear view of the Las Vegas & Tonopah passenger station in Rhyolite. Since the demise of the railroad, the station has been used variously as a private residence, a casino, a gift shop, and a restaurant and bar. Although the structure is now in good condition, the present owner is very old, and local residents have no idea what will happen when she dies. Although the station itself is structurally intact, numerous changes have been made. The trees surrounding it, for example, were no more than seeds during the highlight of Rhyolite. 1978 photos by John Latschar.

Senator Wm. A. Clark

Borax Smith

Bonnie Claire Lake

Rhyolite train station