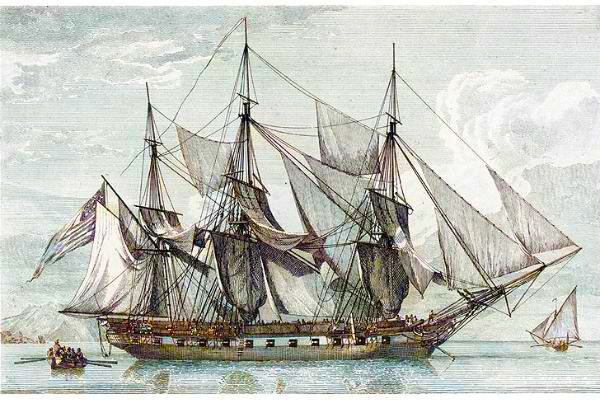

Presideo - San Diego

Presidio - San Diego Historical Society (colorized)

The Presidio* (* Presidio is a name applied to a town which is the residence of the Governor.) of San Diego is about three miles from the harbor in latitude. The buildings are in a square, somewhat like the missions but lower and much decayed. They are on a side hill sloping toward the ocean. The residence of the Governor is on the east, and his entrance commands a fine view of the harbor and the ocean. San Diego contains about 200 inhabitants, exclusive of the mission of the same name, which is about six miles northeast on a small stream that flows into the harbor. The general aspect of the country is hilly and barren, with some scrubby oak and pine on the hills but very little grass.

The harbor of San Diego is formed by two peninsulas, one of which projects into the ocean directly opposite the Presidio. A block house or fort on the peninsula commands the harbor's entrance. The entrance is relatively narrow, but having a great depth of water and being entirely protected from winds, this harbor is considered very safe.

After several days passed, I called again on his Excellency but could get no answer. He told me he did not know what to do. He must see my journal and a copy of my chart and license. He even asked me what business I had to make maps of their country merely to assist me in traveling and, of necessity, be very incorrect as I was destitute of the means for making celestial observations - from this time; I was detained day after day and week after week.

Sometimes he told me I must wait until he could receive orders from Mexico. At other times he thought it desirable that I should go to Mexico and would then conclude that it was necessary to send myself and my party to Mexico. While my fate depended on the caprice of a man who appeared uncertain of anything or the course his duty required him to pursue and only governed by the changing whims of the hour, my feelings can only be duly appreciated by those who have been in the same situation.

I knew the eager expectations with which my party at San Gabriel looked for my return. I felt the ruinous effect of my detention on my business and the gloomy apprehensions that my protracted absence would cause my partners in the distant Mountains. But these considerations never came within the sphere of his Excellency's comprehension.

I was harassed by numerous and contradictory expedient and ruinous delays until about the first of January when his Excellency informed me that if the Americans who were in the harbor of San Diego Masters of Vessels officers and supercargo would sign a paper certifying that what I gave as the reason of my coming to that country they believed to be substantially correct I might then have permission to trade for such things as I wanted and to return the same route which I had come in.

I had applied for permission to travel directly north so that I might arrive as soon as possible on the territory of the United States. He would not grant this, insisting that I should travel the same route by which I had come. The certificate was made out and signed by Capt Wm H. Cunningham. Theodore Cunningham and Mr. Shaw of the Ship Courier Captain Dana and Mr. Robbins of the Waverley Captain Henderson and Mr. Scottie of the brigand belonging to Bags & Company of Lima. The Governor gave me a passport and license to purchase the supplies I wanted.

Although the Governor had obliged me to go to San Diego, he would not furnish me with horses for my return. But I felt this injustice the less than Captain Cunningham offered me a passage on board his ship, which would sail in a few days for point Pedro, the nearest anchorage to San Gabriel. I accepted this offer more readily as it would enable me to prepare my supplies during the passage, for they would be procured from Captain Cunningham. I was allowed the privilege of staying, but four days after I arrived at San Gabriel, I was strictly forbidden to make any more maps for said the Governor; even our citizens can not make maps unless permission is obtained from Mexico. I had found the Governor to more than sustain the character given to him by Se˝oráMartinas. It will be readily supposed that I left him without any other regret than what I felt for the time lost in doing business that might have been done in a few hours or might as well have been left undone. Everything being ready, we sailed and, on the third day, anchored on the east side of the Island of St Catalina.

The Island of Santa Catalina is about 20 miles west-southwest from San Pedro. It is about 18 miles long and eight broad, with high hills covered with grass, wild onions, and some small timber. Captain Cunningham had a house on the island to salt hides. He was about to take some cows, hogs, and fowls for the use of the men there employed. After remaining on the island for two nights, we sailed for San Pedro, a good anchorage or roadstead. Several cannons were fired as a signal to a farmer who lived 8 or 10 miles off, which usually made it his business to come with horses to take people up to the Pueblo or San Gabriel. As the expected horses did not arrive, we started on foot. We continued until we procured horses to take us to the Pueblo Los Angeles or the Angels Village. We remained all night at the village, and in the morning, I called on my friend Se˝or Abella and made arrangements to purchase horses. Then, in company with the Captain Mr. Chapman and Mr. Shaw, I moved on to the Mission of San Gabriel, where I found my party well. I must not omit the cordial welcome with which Father Jose Sanchez received me. He seemed to rejoice in my good fortune and well sustained the favorable opinion I had formed of him. You are now (says he) to pass that miserable country again, and if you do not prepare yourself well, it is your fault. Let me know if there is anything you want that I have, and it shall be at your service. I thanked him for his kindness and made every effort to start as soon as possible. I called on the Commandant to ascertain whether I could stay longer than the four days allowed in my passport. He told me a day or two would not make any difference.

Return to San Gabriel

During my absence, one of my Indian guides, who had been imprisoned, was released by death. The other was kept in the guard house at night and hard labor during the day, having the menial service of the guard house to perform. I took a convenient opportunity to speak to the Father on his behalf. He told me he would do all in his power for his release. From his expression, I thought the government had ordered their imprisonment.

The Fathers had given me some iron, and my smith had made in the shop of the Mission as many horseshoes as I wanted. He had also given me some saddles and the leather for rigging them.

The Fathers had given me some iron.

The Fathers had given me some iron.On the 10th of January 1827, I returned from San Diego. The next day I went down to the Courier, got my supplies, returned to the Pueblo Los Angeles, and put up with my friend F. Abella commenced buying horses and had as many as I wanted in a short time. When I left the Courier, I took leave of my friend Capt Cunningham. If the chance ever throws this in his way, he will perhaps find himself gratified that I have not forgotten his name or friendship. I recollect with the most grateful feelings his kind offices in times that made them doubly valuable and in a country to which he had traveled by the unmarked and challenging ocean paths while my way had been through an unknown land over mountains and parched, inhospitable plains. Meeting in a distant country by routes so different gave an instance of that restless enterprise that has led and is now leading our countrymen to all parts of the world, travelers on every ocean. It can now be said there is no breeze of heaven but spreads an American flag.

.jpg)

Flag of the United States 1822-1836

In this place, I will give some general ideas concerning this country, which may be interesting. As I have observed, California was settled by Missionaries of the order of St. Francis about sixty years since. They established missions in various parts of the country. In civilizing the Indians and imparting them the benefits of religion, they found the opportunity to show absolute power over them. The number of Indians under the control of each Mission varies from 300 to 2000, which are under the care and direction of a priest who has styledáthe Father and who sometimes has a subordinate or two. The Indian has no individual right to the property. However, he said he is interested in his labors and the proceeds of the farms and herds of the Mission. He has not the right or at least the power to marry without the consent of the Father, for the sexes are not allowed to labor together during the day. At night they are shut up in separate apartments. And although since the revolution, they are declared free by express provision, and the fathers ordered them to inform them of the fact, it does not appear that it has made any material change in their situation.

It is not uncharitable, perhaps, to suppose that the fathers, making known their right to freedom, have done it in such a way that it appeared to them from their ignorance a change not to be desired. They said -You live in a good country. You have plenty to eat, drink and wear. Your Father cares for you and will pray for you and show you the way to heaven. On the other hand, if you leave the Missions, where will you find so good a country that will give you clothes, or where will you find a father to feed you, take care of you, and pray for you? Such arguments as these coming from a source long respected and revered and acting on the minds of ignorant and superstitious beings have kept the Indians in their slavery without the desire for freedom. Whatever the causes, very few have inevitably availed themselves of the privilege of the revolution.

The Missions setting aside their religious professions are large farming and grazing establishments conducted at the will of the Father, who is to a certain degree responsible to the President of his order residing in the Province. The immediate supervision of the different kinds of business is confided to overseers who are generally half-breeds raised in a manner somewhat better than the ordinary mass under the eye of the Father from whom they sometimes receive limited education and to whom, in some instances, they might with strict propriety apply the name of the Father. The Indians were employed in the different kinds of work attendant upon farming and herding of stock, the manufacturing of blankets of coarse wool, which form their principal clothing, the making of soap, brick, and distilling. Their labor does not appear to be unreasonably burdensome. They are required to attend church regularly every morning, after which they immediately move off under the direction of their respective overseers to the business of the day.