Indians of the Eastern Mojave

About 11,000 years ago, the region's

ecological

zones were one thousand feet lower in elevation than today due to the

cooler and wetter weather patterns of the waning Ice Age. Streams flowed and lakes existed where

dry lakes

are today. The relative abundance of plant communities supported

wildlife

and indigenous peoples who depended upon the natural resources.

In general, these tribal peoples occupied the lands as small, mobile social units of related families who traveled

in regular patterns and established summer or winter camps in customary places where water and food resources were

available. Archaeologists named a series of five manifestations of Native American occupation, which were believed

to describe changes in

climate,

chipped stone technology, and subsistence practices of these early peoples. These

periods covered time intervals from about 5000 BC to AD 700-900. At that point, the Mojave desert area, unlike

other portions of California's desert region, was influenced by native peoples now called 'Ancestral Pueblo' who

established farming villages along the Muddy, Virgin, and upper Colorado rivers. Their culture reached into today's

Preserve lands at turquoise sources and via trade trails as far as the Pacific coasts. Later, however, Ancestral

Pueblo peoples abandoned their territory and were replaced by Shoshonean and Paiute peoples after about AD 1000.

In addition, native peoples of the lower

Colorado River

basin speaking Yuman languages expanded their river zone territory and utilized some desert lands as well.

Modern Native American "tribes" were products of interactions with the American military and legal system as much

as modern reflections of pre-contact Native American land use patterns, and the land allocated to these groups

frequently did not reflect the actual extent of their pre-Anglo homelands. No tribes directly control any lands

in the Preserve, but historical, archaeological, and ethnographic information indicates that ancestors of the modern

Chemehuevi

and

Mohave

Tribes traveled, camped, hunted, and resided at various places now in the Preserve.

Oral traditions and historical information compiled into maps for the 1950-1960s Federal Indian Lands Claims cases

showed Chemehuevi land knowledge and uses. Some Mohave Tribal members have family histories of being on lands now

within the eastern areas of the Preserve. Certainly, the very detailed and lengthy "song cycles" of the Chemehuevi

identify many places within the Preserve with names and events of supernaturals who performed various activities

there. The "song cycles" were a type of oral map of the territory which had great value to travelers moving through

the area or following seasonal foraging patterns. However, both tribal groups sustained hostilities between themselves,

which was noted by Spanish

Friar Francisco GarcÚs

in 1776. Euro-American contact with peoples now called Chemehuevi or Mohave increased in the nineteenth century.

The Desert Chemehuevi were Native Americans who actually lived most of the year in the area of the Preserve. Limited

food and water resources sustained a low Desert Chemehuevi population density. When food was abundant, it would be

dried and cached for later use. The area of the Preserve probably never supported more than about 150 people at any

one time.

While the Chemehuevi were the primary inhabitants of the area now encompassed by the Preserve, the desert and the

park itself are named for a different group of Native Americans - the Mohave. The Mohave were agriculturalists who

planted in the flooded plain of the Colorado River. This agricultural lifestyle generated food surpluses, which

enabled them to support a sizable population in the river basin area, numbering in the thousands. The Mohave

frequently traded with other Native American groups to the west and east, and had a particular fondness for seashells

traded by Indians on the California coast. The Mohave had a network of trails across the desert from

waterhole

to waterhole. The Mohave bragged to early European visitors that a powerful Mohave runner could make the trip to the

Pacific coast, more than 150 miles long, in three days. The Mohave guided some of the first non-Indian travelers

over this network of trails, including friar GarcÚs in 1776 and American trapper

Jedediah Smith

in 1826. Their network of trails, now known as the Mojave Road, became one of the main routes used by the government

and other travelers to cross the desert before the advent of the railroad.

The Mohave were friendly to GarcÚs and Smith at first, but when Smith returned to recross the river in 1827, the

Mohaves attacked as his party was crossing. Historians later determined that other trappers, arriving between Smith's

two visits, killed several Mohaves and antagonized the rest, prompting the tribe to exact revenge on the next

Euro-Americans they saw. Half of Smith's party was killed, and the explorer led the survivors back across the desert

trails to relative safety in California. This incident created the reputation of the Mohaves as a fierce band that

should be avoided. Further encounters with trappers in the late 1820s and early 1830s led to more bloodshed by Indian

and Anglo alike. Historians hypothesize that the

Old Spanish Trail,

which runs to the north of the Preserve, was created in the 1830s specifically to bypass the Mohave.

In 1848, the United States signed the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo to end the Mexican War and received almost all of

the territory that is now the American Southwest, including all of California and all of the area of the Mojave

National Preserve. Interest in building a transcontinental railroad was high, but the choice of route was difficult

due to sectional controversies. In 1853-54, the United States sent several survey teams into the field to report

on the feasibility of the various routes. One of these was the so-called 35th Parallel Route, which cut through

the eastern Mojave. Two survey parties took the field: one, under Lt. Robert S. Williamson, explored from the western

side and proceeded as far as Soda Lake; the other, under Lt. A.W. Whipple, proceeded from Arkansas to Los Angeles,

crossing the Preserve along the route of the

Mojave Road.

Later attempts proved more successful at opening the cross-desert route now known as the Mojave Road. Between 1855 and

1857, the General Land Office surveyed township lines throughout the area. This effort was largely wasted when the

location monuments could not be rediscovered by others, but the small number of people on the surveying teams became

very familiar with the desert and later served as guides for other expeditions. In 1857,

Edward F. Beale

surveyed a wagon road across the Arizona desert, and crossed the Mojave along the route of the future Mojave Road.

Combined with his eastbound crossing in 1858, Beale's success proved the viability of the wagon road.

Conflict between Native Americans and Euro-Americans was the catalyst for the establishment of a lasting federal

legacy in the Mojave desert. The Mohave attacked emigrant wagon trains in 1858, prompting a substantial military

response. Major William Hoffman led a unit of over 600 men to the

Colorado River,

homeland of the Mohave, and

demanded surrender. Prudently, the Mohave complied, and Hoffman set up a military post on the eastern bank of the

Colorado River that soon became known as Fort Mojave. The effort to supply the fort caused wagon teams from Los Angeles

to cross the eastern Mojave regularly until the start of the Civil War in 1861, and turned Beale's path into a true

wagon road, easily followed. Some improvements were made to the route at this time, such as the construction of a

water stop known as Government Holes.

The U.S. military spent several months in the eastern Mojave in an ill-conceived attempt to punish Native Americans

for a crime they may not have committed. In 1860, two whites were murdered at Bitter Springs, on the Salt Lake Trail,

and the attacks were blamed on the "Pah-Utes," though contemporaries and later historians suggested that the attacks

were quite possibly carried out by Mormons, rather than Native Americans. Newspapers in southern California whipped

the citizenry into a fury, and prompted the army to send a unit led by James H. Carleton, an Army dragoon from

Fort Tejon,

California, into the desert to exact revenge on the Native Americans supposedly responsible for the

attacks. Carleton's troops built a small fort at

Camp Cady,

and roamed all over the western portion of the present-day

Preserve - through Devil's Playground, around the Granite Mountains, and across Soda Lake. The soldiers constructed

a small earthen fortification, called Hancock's Redoubt, at Soda Springs. Carleton chased his quarry all over the

desert, and executed several in an attempt to impress the remainder with the power of the United States military. At

the end of his three-month stay in the desert, the Native American leaders arrived at Camp Cady and asked for peace.

Carleton negotiated a cease-fire, but it was ultimately ineffectual as the army did not return later (due to the

Civil War) to distribute aid as promised and uphold their end of the bargain.

The Civil War prompted the military to abandon Fort Mojave in 1861. In mid-1863, it was re-activated with a garrison

composed of California Volunteers, to provide security for travelers to Arizona. Gold was discovered in Arizona

that year and by 1864, the Mojave Road was a crucial supply line to the territorial capital at Prescott. From 1866

to 1868, the mail was carried over the Mojave Road from California to Arizona. Native Americans in the Mojave and in

Arizona commenced hostilities, and a group attacked the garrison at Camp Cady. This emphasized the importance of

having a military escort for the mail as it crossed the desert. To support this escort effort, the military constructed

small outposts at Soda Springs, Marl Springs,

Rock Spring,

and "Piute" Creek. The army successfully negotiated an

end to the conflict in late 1867. Shortly thereafter, a series of heavy rainstorms left the road impassible. This

factor, combined with the cumulative losses to Native Americans along the Mojave route, caused the transfer of mail

service to a different, more southerly trail. The outposts at

Piute Creek,

Rock Spring, Marl Springs, and Soda Springs were abandoned.

Military use of the Mojave Road diminished, but civilian use increased as more people were attracted to the desert

area. By the 1870s, Fort Mojave was largely supplied by steamboat service up the Colorado River, but miners,

prospectors, and ranchers used the

Mojave Road

to cross the desert until the Southern Pacific / Atlantic & Pacific Railroad was completed in 1883.

Soda Springs - Mojave Preserve

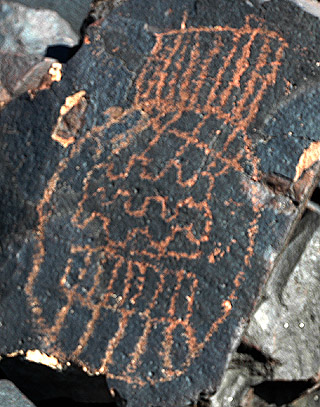

Petroglyph - East Mojave Desert

Spirit Mountain - Colorado River

The Needles - Colorado River

Soda Dry Lake - Mojave Preserve

Site of Camp Cady - Mojave River

Camp Beale's Springs - Kingman, Arizona

Quarters at Fort Tejon