Railroads around the Mojave National Preserve

The Salt Lake Route

Another railroad destined to operated through the

heart of what now is

Mojave National Preserve,

from

northeast to southwest, would operate under three different

names:

San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad

from its completion in 1905 until 1916; Los Angeles &

Salt Lake Railroad from 1916 to 1988; and overlapping

with that second name, Union Pacific Railroad from the

1920s to the present.

The idea of a railroad connecting

Salt Lake City with southern California probably went

back practically to completion of the first transcontinental

railroad at Promontory Station in May 1869, which was

followed by construction of the Utah Central from Ogden

on the

Union Pacific

to Salt Lake City, making the capitol

of Utah Territory a railroad town, and the Union Pacific

would soon take over the Mormon-built Utah Central.

The first concrete evidence of Union Pacific intentions

consisted of the Union Pacific interests pushing construction

of a subsidiary Utah Southern southwest from Salt

Lake City to Milford, Utah. Union Pacific interests then

played with the idea of an extension southwestward

across Utah and Nevada to a connection with the

Southern Pacific at

Mojave,

but the Union Pacific entered an

era of financial difficulty and reorganization in the 1880s

and 1890s, though during 1888 Union Pacific surveyors

worked on a line from Milford to

Barstow

with the intention

of reaching Los Angeles. In 1890 the Union Pacific

actually built about 145 miles of grade from Milford to

Pioche, but after laying a mere eight miles of track on it,

construction stalled.

Then the faltering Union Pacific went

into bankruptcy in the silver crash of 1893 and was not

reorganized and rejuvenated under the direction of Edward

Henry Harriman until 1898. Meanwhile the railroad

picture became greatly complicated, more a part of Utah’s

history than that of Mojave National Preserve, and while

the Union Pacific was stalled, in 1900 a copper magnate

from Butte, Montana, named William Andrews Clark,

who was also a United States Senator, entered the competition

initiating a two year contest between Clark and

Harriman.

In a brilliant move, Clark bought the Los Angeles

Terminal Railway, which gave him a railroad route

through and base in Los Angeles, and initiated surveys for

a railroad to Salt Lake. Covertly he had also bought the

assets of a corporation that had never built any railroad,

the Utah and California Railroad, which however had

rights to a surveyed route from Salt Lake City across Utah

to the Nevada state border. In one brief coup, Clark had

the two ends of his Salt Lake to Los Angeles Railroad;

now he had to acquire rights across Nevada and the rest

of California, and build a railroad between Salt Lake City

and Los Angeles using those rights.

What followed was an

incredibly complex contest between Clark and Harriman

involving lawyers, courts, legislatures, newspapers, competing

grading crews, and every weapon either magnate

could bring to bear, the result of which was a secret compromise

on July 9, 1902, in which Harriman agreed to sell

portions of Union Pacific-owned (technically Oregon Short

Line Railroad) grade and track to Clark in exchange for

50 per cent of the stock in Clark’s San Pedro, Los Angeles

& Salt Lake Railroad. Thereafter, construction continued

eastward from Los Angeles and westward from Utah, to

a joining of the rails at an empty piece of Nevada desert

roughly 27 miles west of Las Vegas on the afternoon of

January 30, 1905.

As was typical of railroads at the beginning of the 20th

Century, the San Pedro, Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad

established side tracks or passing tracks often accompanied

by a section house and bunk house for the maintenance

crews known as section gangs about every ten or

fifteen miles along the railroad, some of these with water

tanks to provide locomotives with boiler water, occasionally

a wye track, and so forth. The railroad established

a number of these across what now is Mojave National

Preserve, the most important being a “helper station” at

a place called Kelso, which would be a base for “helper”

locomotives which would be coupled on the front of

eastbound trains to “help” them climb the grade to the

summit at Cima, after which the helper locomotives would

be uncoupled, turned on the wye track at Cima, and run

back “light” or without train to Kelso to await their next

helper assignment. As a helper station, Kelso required an

engine house and eventually its replacement with a larger

roundhouse, and crews of mechanics and others to help

keeping the railroad running, as well as a restaurant or

eating house and some accommodations for train crews

staying overnight between runs. Thus Kelso, in the middle

of the Mojave Desert at a location where the railroad had

acquired springs and wells to serve as reliable sources for

boiler water for locomotives, became a railroad company

town, with company housing and other such facilities.

The first through passenger train on the new railroad

started out from Salt Lake City for Los Angeles on February

9, 1905, carrying, among others, Senator Clark. The

Salt Lake Route was equipped with a stable of modern

standard gauge steam locomotives, most equipped with

partly cylindrical Vanderbilt tenders, and the latest of

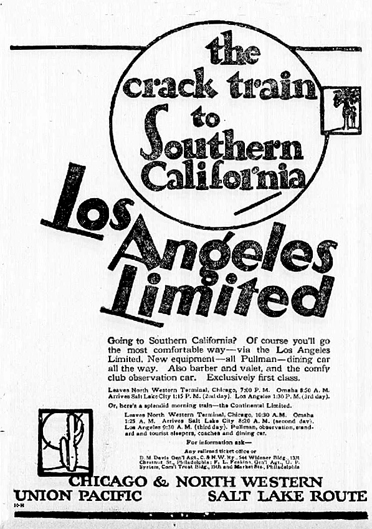

passenger cars. It soon had a premiere train, The Los

Angeles Limited, which would remain the most prestigious,

Pullman-sleeping-car-equipped train on the railroad.

Whereas most of the line’s passenger trains stopped for

the passengers to have meals at stations such as

Kelso,

Las Vegas,

Caliente, and Milford, The Los Angeles Limited

had its own dining car and did not need to make

meal stops. It was not until the mid-1930s brought new

technology of locomotives powered by Winton and later

diesel-electric engines pulling new “lightweight” streamlined

passenger cars that a still newer train, the Armour

yellow City of Los Angeles eclipsed the Limited as

the principal train on the line.

The railroad remained the San Pedro, Los Angeles &

Salt Lake Railroad until 1916 when management of the

line decided to shorten the name, dropping the words

“San Pedro” to make it simply the “Los Angeles & Salt

Lake Railroad.” Five years later, in 1921, the company

persuaded Senator Clark to sell his 50 per cent interest

in the line, and the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad became

a wholly-owned subsidiary of the Union Pacific Railroad.

Unlike most such instances, when the Union Pacific

dissolved and absorbed the property of a subsidiary into

its own corporate structure, in the case of the Los Angeles

& Salt Lake Railroad, the Union Pacific retained it as a

separate company until 1988, when it was finally dissolved

and absorbed into the Union Pacific Railroad. Until that

time it was common for locomotives owned by the L.A.&

S.L. to carry the name “UNION PACIFIC” in large letters

but to have elsewhere on cabs or tenders or both of steam

locomotives the initials “L.A.& S.L.”

Commonly called the Salt Lake Route, the line

featured a number of fairly ordinary depots and eating

houses, many of them wood frame, until the early 1920s

when Union Pacific management caught a contagious

disease that might be termed either “Santa Fe Envy” or

“Fred Harvey Envy.” The

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe

System had worked out with an entrepreneur named

Fred Harvey

in the 1870s an agreement under which Harvey

took over and managed railroad depot eating houses

and depot hotels. Harvey had very definite ideas about

how such establishments should be operated, hired first

rate chefs, obtained the highest quality of fresh meat,

poultry and produce, installed the finest of linen and

china, and employed energetic young women uniformed

in black dresses with white aprons as waitresses, this in

an era where railroad eating houses were notorious for

their awful coffee, their stale sandwiches with desiccated

bread, rancid meat, and rubberized cheese, greasy China

and implements, and dirty employees. After the Santa Fe

bankruptcy in the 1890s and its reorganization, under a

new president named Edward Payson Ripley the company

began hiring first rate architects to build attractive permanent

depot hotels, depots and eating houses in Spanish

mission revival, English Tudor half-timbered, Moorish and

neo-classical Palladian designs. This was the competition

the Union Pacific faced after the end of World War I, and

west of Mojave National Preserve at Barstow the Santa Fe

and Fred Harvey had their Moorish-style depot hotel and

restaurant known as

Casa de Desierto,

or “house of the

desert,” and east of Mojave National Preserve at Needles

the railway had its neo-classical, Palladian Harvey House

and restaurant known as

“El Garces”

after a Spanish

padre of that name, both impressive pieces of architecture.

Worse, west of

Daggett

through

Barstow

and over

Cajon Pass

to

San Bernardino,

the Union Pacific shared

joint trackage with the Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe, so

that westbound travelers on Union Pacific trains who had

been fed at little board and batten eating houses across

Utah, Nevada and at Kelso, now passed by the elegant

depot restaurants and hotels the Santa Fe had to offer its

passengers. Eastbound, after passing such structures, they

were then faced with the Salt Lake Route’s rough facilities

from Daggett to Salt Lake City. So it should not be surprising

that by the early 1920s the Union Pacific, infected

with Fred Harvey envy, should decide to build at Milford,

Utah, Caliente and

Las Vegas, Nevada, and Kelso and

Daggett, California, attractive new depot-eating-house-hotel

combinations all in the California mission revival

style, emulating the style of some of the Harvey Houses

such as the Alvarado in Albuquerque. And thus it was in

1923 and 1924 that Kelso, California acquired a spiffy new

depot, eating house and hostelry which the National Park

Service now owns and has just finished restoring as a visitor

center for Mojave National Preserve.

The Union Pacific continued operating passenger trains

through Kelso until 1971, when the Federally chartered

National Railroad Passenger Corporation, better known as

Amtrak, took over most of the national’s passenger trains.

On the Salt Lake Route, Amtrak operated a through

streamlined passenger train known as the Desert Wind

between Salt Lake City and Los Angeles until May 10,

1997, when it was discontinued, and earlier operated a

“Las Vegas Fun Train” between Los Angeles and Las

Vegas, Nevada. Since the discontinuance of the Desert

Wind. the Salt Lake Route has experienced no passenger

traffic across its line. Only freight trains now pass across

Mojave National Preserve, but freight traffic has grown

to such proportions that the Union Pacific is preparing to

convert the main line across Mojave from single track to

double track. Meanwhile, the Salt Lake Route from its

completion in 1905 to the present, connecting with the

Union Pacific at Salt Lake City and Ogden, has offered

that company another transcontinental railroad connection

as well as access to the markets of southern California, so

with its operation Mojave National Preserve had not only

one transcontinental railroad along part of its southern

boundary, but another right across its heart!

Kelso, California (location and history in Mojave Desert)

Las Vegas, Nevada (overview of the city in a Mojave Desert context)

Casa del Desierto, the historic Harvey House in Barstow

El Garces Harvey House and depot hotel in Needles

Daggett, California (history and local significance)

Barstow, California (regional center with historic rail connections)

Cajon Pass (mountain pass and key railroad route)

San Bernardino, California (major city and rail hub)

Las Vegas, Nevada (listed again later in the text)

Union Pacific Railroad history page

Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad overview

Fred Harvey and Harvey House system background

Page Summary

The Salt Lake Route, completed in 1905, was a major railroad linking Salt Lake City to Los Angeles. Originally built by Senator William A. Clark after a rivalry with Union Pacific, the line crossed what is now Mojave National Preserve. Key stops like Kelso supported train operations, with helper engines assisting trains over steep grades. Kelso became a full company town with a depot, restaurant, and housing. In the 1920s, Union Pacific upgraded depots along the route to compete with Santa Fe’s Harvey Houses. Passenger service ended in 1997 when Amtrak discontinued the Desert Wind, though freight trains still run. The route gave Union Pacific a second transcontinental line and remains vital today, with plans for double-tracking to handle increasing freight across the desert’s core. The Kelso Depot is now a visitor center.

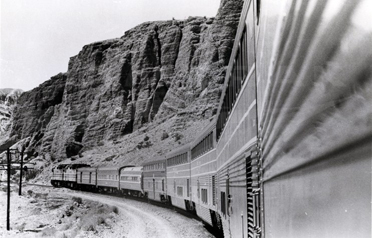

In this photograph, the Desert Wind (Ogden-Las Vegas-Los Angeles) has a varied consist of old and new rail cars. Behind the locomotives are a Heritage Baggage car; Heritage Sleeping car; Amdinette; and bi-level Superliner coaches. The single-level Amfleet equipment, built mainly for use in the East and Midwest, was introduced in 1975, and the Superliners, designed for use on western long-distance routes, went into service in 1979. The Desert Wind was not equipped with Superliners until June 1980. Located about 40 miles northeast of Barstow, California, Afton Canyon was carved by the Mojave River, which for most of the year is not visible above ground.

The Desert Wind was established in 1979 during a major route restructuring mandated by Congress. Years later, the train was combined with the California Zephyr east of Salt Lake City for through service to Chicago. In 1997, the train was discontinued.

Los Angeles Limited

Beginning in 1905 the Los Angeles Limited was the flagship train of the Union Pacific between Chicago and Los Angeles.

In the 1950s ridership on the Los Angeles Limited declined rapidly.