Shrubs

Creosote bush

SPECIES: Larrea tridentataCOMMON NAMES :

creosotebush

greasewood

LIFE FORM :

Shrub

GENERAL DISTRIBUTION :

Creosotebush occurs throughout the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts. Its distribution extends from southern California northeast through southern Nevada to the southwest corner of Utah and southeast through southern Arizona and New Mexico to western Texas and north-central Mexico.

HABITAT TYPES AND PLANT COMMUNITIES : Creosotebush is a dominant or codominant member of most plant communities in the Mojave, Sonoran, and Chihuahuan deserts. Creosotebush occurs on 35 to 46 million acres in the Southwest. Creosotebush usually occurs in open, species-poor communities, sometimes in pure stands. It also occurs as a transitional species in desert grasslands, mesquite woodlands, Joshua tree (Yucca brevifolia) communities, and dry desert wash areas.

The creosotebush-white bursage (Ambrosia dumosa) association covers approximately 70 percent of the Mojave Desert. Species associated with creosotebush-white bursage communities in the Mojave Desert include Shockley's goldenhead (Acamptopappus shockleyi), Anderson's wolfberry (Lycium andersonii), range ratany (Krameria parvifolia), Mojave yucca (Yucca schidigera), California jointfir (Ephedra funerea), spiny hopsage (Grayia spinosa), and winterfat (Krascheninnikovia lanata). Creosotebush also occurs in the Mojave Desert scrub association with desertholly (Atriplex hymenelytra), shadscale (A. confertifolia), white burrobrush (Hymenoclea salsola), blackbrush (Coleogyne ramosissima), Joshua tree, desertsenna (Cassia armata), and Nevada ephedra (Ephedra nevadensis).

IMPORTANCE TO WILDLIFE :

Many desert animals bed in or under creosotebush. Desert reptiles and amphibians use creosotebush as a food source and perch site and hibernate or estivate in burrows under creosotebush, avoiding predators and excessive daytime temperatures. Desert tortoises dig their shelters under creosotebush where its roots stabilize the soil. Banner-tailed kangaroo rats frequently use creosotebush for cover. Merriam's kangaroo rats often make their dens under creosotebush. Some subspecies of kit fox rest and den in creosotebush flats.

Many small mammals browse creosotebush or consume its seeds. Creosotebush comprised 14.6 percent of black-tailed jackrabbit diets on Isla Carmen in the Gulf of California. Terminal twigs of creosotebush were consumed in proportion to their availability in black-tailed jackrabbit habitat. Ninety percent of creosotebush were browsed, and 52.5 percent of twigs on those plants were browsed. Creosotebush dominated the diet of desert woodrats in the Mojave Desert of California; the desert woodrats strongly preferred creosotebush foliage of relatively low resin content. It has been found that 27.5 percent of creosotebush seed mericarps on a Mojave Desert site showed signs of postdispersal rodent predation.

PALATABILITY :

Creosotebush is unpalatable to most browsing wildlife.

COVER VALUE :

Creosotebush in Utah provides good cover for small mammals and nongame birds, fair cover for pronghorn and upland game birds, and poor cover for bighorn sheep, mountain goats, and waterfowl.

OTHER USES AND VALUES :

Creosotebush has been highly valued for its medicinal properties by desert peoples. It has been used to treat at least 14 illnesses. Twigs and leaves may be boiled as tea, steamed, pounded into a powder, pressed into a poultice, or heated into an infusion.

Creosotebush is host to an insect, Tachardiella larreae, which produces lac and deposits it on the stems of creosotebush. Lac is plastic when heated but hardens again on cooling, forming a strong bond like commercial sealing wax. Lac has been used by desert peoples to seal lids on food jars.

BOTANICAL AND ECOLOGICAL CHARACTERISTICS

SPECIES: Larrea tridentata

GENERAL BOTANICAL CHARACTERISTICS :

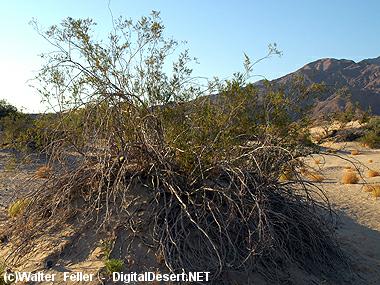

Creosotebush is a native, drought-tolerant, evergreen shrub growing up to 13.2 feet (4 m) tall. Its numerous branches are brittle and densely leafy at the tips. Because of leaf and stem alignment, creosotebush provides little shade during the full desert sunshine.

The root system of creosotebush consists of a shallow taproot and several lateral secondary roots, each about 10 feet (3 m) in length and 8 to 14 inches (20-35 cm) deep. The taproot extends to a depth of about 32 inches (80 cm); further penetration is usually inhibited by caliche. Root growth is inhibited by high concentrations of salt (>10,000 ppm). Creosotebush roots require relatively large amounts of oxygen for growth.

REGENERATION PROCESSES :

Creosotebush reproduces both vegetatively and sexually.

Vegetative reproduction: Creosotebush achieves its status as one of the most stable members of desert communities by cloning. When drought is extreme, old branches and roots of creosotebush die back. When rains return, branches are replaced by sprouts originating near the outside of the root crown. Creosotebush clones gradually expand to form rings many meters in diameter. Creosotebush may occasionally sprout from its root crown after disturbance.

Sexual reproduction: Age distribution in many stands of creosotebush indicates that germination and survival under natural conditions are rare. Sexual reproduction may be especially rare at the upper elevational limits of creosotebush.

Creosotebush requires summer rains for successful sexual reproduction. The flowering success of creosotebush is greatest with moderate rainfall. In years of high rainfall, a high proportion of flowers is diseased.

The trichomes are not stiff enough to penetrate animal skin, and the seeds are too heavy for lofting. However, it has been suggested that the shucking and burial of creosotebush seeds by rodents may facilitate the germination and survival of creosotebush. It has been noted poor creosotebush reproduction on level plains. More seedlings established if the soil surface was broken or scarred. Creosotebush may be more abundant on southern or northern slopes of a pediment than in washes. Rock crevices and irregularities of the pediment may provide protection and footholds for wind-tumbled seeds.

Germination of creosotebush is related to rainfall. A minimum of about 1 inch of rainfall seems necessary to induce germination. A 1971 rain of 1 to 1.96 inches (25-49 mm) in the Mojave Desert was sufficient, but neither an August 1972 rain of 0.68 inch (17 mm) nor a July rain of 0.84 inch (21 mm) promoted germination of creosotebush seeds. If less than 2 to 3 inches (50-80 mm) or more than 6 inches (150 mm) of rain fall during the summer, germinability of seeds is usually less than 20 percent. If 3 to 6 inches (80-150 mm) fall, germination is 20 to 60 percent.

SITE CHARACTERISTICS : Creosotebush commonly grows on bajadas, gentle slopes, valley floors, sand dunes, and in arroyos at elevations up to 5,000 feet (1,515 m) throughout the Sonoran, Mojave, and Chihuahuan deserts. It occurs on calcareous, sandy, and alluvial soils that are often underlain by a caliche hardpan.

Temperatures in the southwestern deserts are variable and extreme. Near the southern boundary of creosotebush distribution, at Puerto Libertad, Sonora, the mean annual temperature is 68.37 degrees Fahrenheit (20.2 degrees C). Daytime temperatures in the summer often reach 117 degrees Fahrenheit (47 deg C). In Rock Valley, Nevada, near the northern boundary of creosotebush distribution, temperatures range from 5 degrees Fahrenheit (-15 deg C) in winter to 117 degrees Fahrenheit (47 deg C) in summer.

Phenological events in the southwestern deserts are triggered by rain. In the Sonoran Desert, annual rainfall averages 4 to 12 inches (100-300 mm) and is distributed bimodally. The Mojave Desert gets more winter than summer rain; in Rock Valley, Nevada, rainfall averages 5.524 inches (138.1 mm), with 60 percent falling between September and February. The Chihuahuan Desert is slightly less dry; in the Rio Grande Valley, New Mexico, rainfall averages from 8.5 inches at San Marcial to slightly more than 10 inches at Socorro. Two-thirds to three-fourths of the precipitation falls between April 1 and September 30.

Low soil oxygen may be a controlling factor in the distribution of desert species. Creosotebush is less tolerant of low soil oxygen than white bursage. Creosotebush does not grow in fine-textured and poorly drained soils due to its high oxygen requirement.

SUCCESSIONAL STATUS :

Creosotebush density and cover are generally decreased by disturbance. In a comparison between vegetation on disturbed and undisturbed Mojave Desert sites, creosotebush was dominant on all control sites and subdominant to white bursage on disturbed sites. Desert succession can be described using life-history strategies: Species with high recruitment and mortality rates, such as white bursage, are dominant in the colonizing stage and species with low recruitment and mortality, such as creosotebush, eventually dominate the landscape, although colonizing species usually remain present.

Recruitment of creosotebush is infrequent. Despite the abundance of potentially suitable areas beneath white bursage, young creosotebush have been found beneath only 1 percent of all white bursage. Total densities of young creosotebush were between 12 and 15 plants per hectare. The density of white bursage plants was ten times that of creosotebush. Although large-scale creosotebush seedling establishment does not occur after disturbance, relict creosotebush usually increases in size by cloning. Creosotebush canopies may grow to exceed the coverage of white bursage by more than six times.

Creosotebush exhibits root-mediated allelopathy. In a laboratory study, creosotebush test roots grew freely through soil occupied by white bursage roots, but white bursage test roots grew at reduced rates into soil occupied by creosotebush. Mature creosotebush may be allelopathic to their own seedlings, encouraging an open community structure.

SEASONAL DEVELOPMENT : Creosotebush leafs out in response to spring, summer, or fall rains. Creosotebush usually flowers in May in the Mojave Desert, but it can flower anytime during the summer if it receives enough rain. In the Sonoran Desert, most creosotebush seeds are shed in the summer, but creosotebush in the Chihuahuan Desert does not shed its seeds until fall. Creosotebush seeds germinate after rains from mid-June to mid-September in the Mojave Desert.

Also see:

King Clone

Creosotebush is known to attain ages of several thousand years; some creosotebush clones may be the earth's oldest living organisms. The age of the largest clone in Johnson Valley, California, is estimated at 9,400 years. The average estimated longevity of creosotebush may be about 900 years.

The leaves of creosotebush are thick, resinous, and strongly scented. Flowers are solitary and axillary. Fruits are globose, consisting of five united, indehiscent, one-seeded carpels which may or may not break apart after maturing. Each carpel is densely covered by long trichomes.

Mature creosotebush may be allelopathic to their own seedlings, encouraging an open community structure.

Creosotebush uses white bursage as a nurse plant. Generally all young creosotebush were rooted beneath the canopies of live white bursage or positioned next to dead ones. The smallest creosotebush plants were all associated with live white bursage. Most creosotebush establishment apparently occurs near live white bursage.

Ball-shaped leafy galls, about the size of walnuts, are common on stems. These galls are caused by a small gnat-like insect known as the creosote gall midge, Asphondylia auripila. The larvae of the midge live in these. The younger galls often appear green and older galls are brown.

Creosotebush seeds are primarily adapted for tumbling rather than for animal dispersal or lofting. The stiff trichomes radiate equally in all directions so that little wind is required to send the seeds tumbling.

Many animals bed in or under creosote bush. Desert reptiles and amphibians use creosotebush as a food source and perch site and hibernate or estivate in burrows under creosotebush, avoiding predators and excessive daytime temperatures. Death Valley National Park

A chuckwalla lizard surveys the creosote landscape from his rock, looking for a mate.

Also see:

Desert Habitats