Chapter IV.

The Outfit

DEATH VALLEY was the goal, but after the day at Saratoga Springs one thing was certain: no matter if we could get there in an automobile—and various expedients were suggested to make it possible, even safe —not thus would we enter the White Heart, not with the throbbing of an engine, not dependent on gasoline, not limited in time, not thwarted by roads. When we went it would be slowly, quietly, camping by the springs, making fires of the brush, sleeping under the open sky, listening, watching. We had found the outdoors on the desert a wonderful thing and we wanted to live with it a while. If the White Heart was the climax of Mojave we felt that it must be a climax of the feel of the outdoors, one of its supreme expressions. We were going on a pilgrimage to that. The Outfit

The OutfitSuch a pilgrimage meant an outfit, either a wagon or a pack-train, and a guide. We needed a man accustomed to living on the desert, who knew the valley thoroughly, who could work in its heat and brightness, and who had the courage to take two ignorant enthusiasts there. We had lost the easy assurance with which we had talked at Joburg about going to Death Valley. No wonder the inhabitants of that town had been stunned when we said that we were on the way there! The unspeakable road beyond Saratoga Springs and the little gravel-ridge which we could not climb were sufficient warning of the nature of the undertaking. Mojave is not easily to be known as we would know her. She keeps herself to herself. The season added a further complication. Soon it would be April and the heat in the valley would be too great for us to endure. The pilgrimage must start no later than January. That meant going home and coming back. As usual the way to the valley bristled with difficulties.

We talked to the Sheriff about it. Julius Meyer was nearing fifty, a lean, strong-looking man. He had a fine face, very somber in repose as though he had met with some lasting disappointment, but wonderfully lit by his occasional smile. His eyes had the hard clearness which living on the desert seems to produce. They looked straight at you. He said little, the kind of man who announces his decisions briefly and carries them out. Mrs. Brauer said of him: "Julius is good." Beyond her praise and the impression which he made we knew nothing of him except the incident of the little fishes and that he had lived twenty years on the desert and had once traveled the length of Death Valley with burros; but we had no hesitation in asking him to be our guide. He said it was a mad idea. Nobody ever went to Death Valley unless they expected to get something out of it, and then they took a Ford if they could find one and hurried.

"We are just like the rest of them," we told him. "We expect to get something out of it, but we can't get it in a Ford."

He finally agreed to go if we would take a wagon. He refused to consider a pack-train, saying that we would never be able to pack burros, and walk beside them and ride them in the heat of the valley. He did not take the discussion very seriously, for he evidently did not expect us to return. He thought the glamour of Mojave would wear off. Nevertheless it was a promise, and we were certain that when such a man promised we would see the White Heart. During the following summer and autumn we kept hearing snatches of Mojave's songs. A bit of pure cobalt in the depths of the woods, the flash of the sun on the tops of waves, the clear lovely blue of ruts in a sandy road echoed her. Thinking of her the eastern sun seemed a trifle pale, the gay brightness of summer a little dim. We loved the familiar, dear New England landscape, but we were under the "terrible fascination." Only the sea was like Mojave. Often Charlotte and I would take our blankets to a lonely part of the beach and spend the night there. Never before had we slept outdoors, on the ground under the stars. Knowing Mojave even a little had made us feel that it might be worth while. We found that it was.

"We have to get used to it," we told our astonished friends. "When we go to Death Valley with the wagon we will have to sleep on the ground."

We did get used to it and in December wrote the Sheriff. This telegram came:

"O. K. Julius Meyer."

When we appeared for the second time at Silver Lake in the big automobile we were greeted with even greater amazement than before. We had driven over from Barstow and traveling on the desert for pleasure is so novel an idea that everybody thought us insane. There were a few more people in town than we had found on our former visit, a commercial traveler and three or four miners, among them a brigand known as French Pete, with his head tied up in a red handkerchief. They all took a lively interest in the proposed expedition and gave advice. They were courteous, but amusement contended with wonder behind their friendly eyes. They tried to be kind and searched their minds for something good to say of the frightful valley. Each one separately told us what was its real, true attraction.

"You see the highest and the lowest spots in the United States at the same time. Mount Whitney, you know, and the bottom of the Valley."

Since we had never been able to see Mount Whitney in any of our travels on the Mojave, we wondered how we should be able to see it from the deep pit of the valley with the Panamints between, but receptivity was our role. The highest and lowest became a sort of slogan. Sooner or later everybody we met at Silver Lake or on our way to the valley said it. We waited for them to say it and recorded it in our diaries: "Explained about H. and L."

The Sheriff had procured a wagon drawn by a horse and a mule to start from Beatty, a hundred miles further up the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad, and much credit is due him for the gravity with which he embarked on the folly. After the O. K. telegram he never expressed the slightest doubt of the feasibleness, the sanity, and even the usualness of the proceeding. What we needed more than anything else was a real reason for going, seeing the desert and having an adventure with the outdoors being no reasons at all. He furnished even that. Charlotte had brought her sketching-box; he saw it among the camping-paraphernalia, asked what it was, and instantly spread the report that we were artists in search of scenery. We had the presence of mind never to deny this and by refraining from exhibitions were able to be both notorious and respectable.

We abandoned the automobile and traveled up to Beatty on the railroad, a seven-hours'-journey. On the morning of train-day our bed-rolls and duffle-bags on the station-platform, and ourselves getting into the coach in knickerbockers and tough, high shoes created more excitement than Silver Lake had known for some time. Even Mrs. Brauer came out, and Mr. Brauer stood with his hands in his pockets, beaming on the crazy line of freight cars and the heads stuck out of the windows of the coaches, chuckling and chuckling. There was a Pullman from Los Angeles hitched to the tail of the train, very grand, with all the window-shades still pulled down so early in the morning. Our guide, who felt his responsibilities, was chagrined because he could not get us places in it; but we were more than content, especially when the conductor, who had a black mustache worthy of one of Stevenson's pirates and wore no uniform, assured us that the coach was not supposed to be a smoking-car so our presence would interfere with no one's happiness. It was full of old-timers who were all remarkable for the clearness of their eyes. They were friendly and courteous, men past middle age, dressed in overalls and flannel shirts, who got off at Zabrisky and such places, where it is hard to see that a town exists. The younger men, and the more prosperous looking in business-suits were mostly bound for Tonopah, one of the most active mining-centers left in the country. During the day many of our fellow-passengers talked to us, stopping as they went up and down the aisle to sit on the arm of the opposite seat. The talk was of mining prospects, the booms of Goldfield and Tonopah, speculation in mining-shares, the slump after the war began, the abandoned towns, the river of money that has flowed into the desert and been drunk up by the sand. They all agreed that Death Valley was a desperate place, there had never been any mining there to amount to anything. To encourage us they never failed to mention H. and L., but they thought we would find more to interest us in the mining towns of Nevada. They made them picturesque with pioneering stories.

The railroad runs along the east side of Death Valley, separated from it by a range of mountains. It follows the course of the Armagosa River as it flows south through the desert. In some places the river-bed was full of water, in others it was a dry wash. Where the water is certain large mesquites and Cottonwood trees grow and the mining stations, consisting of a store and one or two houses, are nearby. The mountains along the route are scarred with mines and prospect holes. At Death Valley Junction a branch road goes to the large borax-mine at Ryan on the edge of the valley. The country is very desolate. Soon after leaving Silver Lake we passed a group of big sanddunes with summits blown by the wind into beautiful, sharp edges. From that viewpoint they seemed to guard the shining illusion that always beckoned behind the Avawatz. We had seen them on the way to Saratoga, but so far off that they had looked like little mounds. They are a miniature of the Devil's Playground, that utter desolation of shifting sand south of Silver Lake where no roads are. Now we passed near enough to see their impressive size and how the wind makes their beautiful outlines. When the sand is deep and fine the wind is forever at work upon it, blowing it into dunes, changing their shapes, piling them up and tearing them down. It gradually moves them along in its prevailing direction by rolling their tops down the lee side and pushing up the windward side for a new summit. The dunes literally roll over. The artist who had boasted of his city at Silver Lake called them the "marching sands." North of the marching sands we traveled through graygreen mesas much broken by rugged, mountainous masses, a forbidding and stern land.

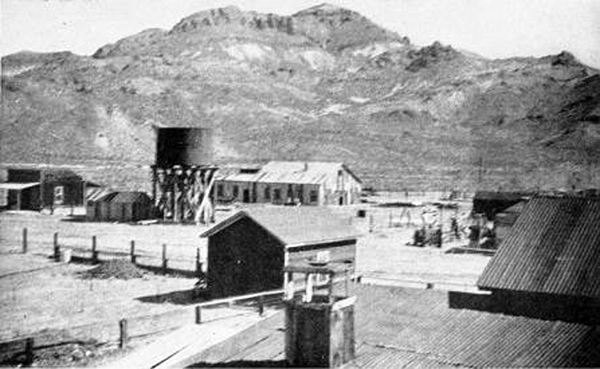

Beatty has a magnificent location at the base of a big, red mountain in front of a greater, indigo mass. It was once a prosperous mining town, but was at that time partly deserted and many of the small wooden houses stood empty. Every effort had been made to give the appearance of streets by fencing off yards around the houses, but it was hard to get the scheme of Beatty. The first impression was of houses set down promiscuously on the sand. Some of the yards had gardens where, by means of constant watering, fruit-trees and roses were made to grow. Beatty is at a considerable altitude so that while the noonday sun was hot the nights were cold, sometimes below freezing. The air was marvelously clear. On the brightest days in the east flowers and shrubs look as though they were floating in a pure, colorless liquid, and the vistas are softly veiled. The air seems to have substance. Among the mountains of the desert it is a flawless plate glass through which you look directly at the face of the world. Distant outlines stand out boldly, and every little shining rock and bush is set firmly down.

Prohibition had hit Beatty hard. Most of the ground-floor of the hotel consisted of a big poolroom and bar over which hung an air of sadness. We had an impression of moving-day in that forlorn hour when everything is dismantled and the van has not come. The landlady apologized for the accommodations which, however, were excellent.

"We used to keep it up real nice before mining slumped," she said, "but now there is prohibition, too, and we are clean discouraged."

She was an ingenious person. In her front yard, one of the prettiest in Beatty, the walks and flower-beds were edged with empty bottles driven in neck down. They made a fine border, durable, with a glassy glitter in the sun.

At Beatty we first encountered Molly and Bill. Molly was a white mule and Bill a big, thin, red horse. They were hitched to an ordinary grocery wagon. Our guide seemed pleased with them, but we were doubtful. He had rented them from an Indian and said that they were absolutely desert-proof, they could live on nothing at all and drink soda-water forever. Bill looked as though he had always lived on nothing at all, and Molly laid back her long, white ears in a manner unpleasantly suggestive. Moreover, it did not seem possible that the frail-looking wagon could carry the supplies and the camping equipment. We had purchased food for a month. It was both heavy and bulky; bacon, ham, potatoes, flour, canned milk and vegetables, four pounds of butter and six dozen eggs. It was the Sheriff's selection; Charlotte and I had not expected to travel deluxe like that. Indeed we had brought some dried potatoes and vegetables and had not dreamed of things like milk or butter or eggs. He made quite a stand for the real potatoes, so they had to go along. In spite of their bulk the canned milk and vegetables are almost necessities on the desert, where the water is scarce and bad, for things that have to be soaked a long time and cooked in the alkali water are hardly edible. He had a weakness for green California chilies and horehound candy, so they also were included. Charlotte insisted on dried fruit, especially prunes. The grub alone made a formidable pile on the porch of the general store. In addition there was a bale of hay and a bag of grain. It looked like very little for the dejected Molly and Bill, but the Sheriff said that we could buy more at Furnace Creek Ranch in the bottom of the valley, and that we need only feed them while we were actually in the valley, for as soon as we went up a little way on either side they could forage. We looked anxiously out over the environs of Beatty, which is fairly high-up. They were precisely like the environs of Silver Lake, where the half-wild burros can scarcely find a living. We began to worry in earnest. By the time the food for man and beast was on the wagon worry turned to despair. It was full, and the three beds, the duffle-bags, the sketch-box which we clung to as the only proof of sanity, and the three five-gallon gasoline cans for carrying water were still on the ground.

"It can't be done," we told the Sheriff. "You will have to make some other arrangement."

"Now look here," he replied. "You stop worrying. Nobody in this outfit is to worry except me. That's my job. It's what I'm for." His hard blue eyes looked into ours with determination, then he grinned and from that moment became the Official Worrier.

Slowly and patiently he built up a monumental structure and cinched it with rope and baling wire. Everything found a place. As we expected to make a spring that night it was not necessary to fill the gasoline cans. They were hung on the back of the load with more balingwire. Remembering the day when it had been 95 degrees at Saratoga Springs we tried to leave our heavy driving-coats behind, but were forcibly forbidden to do so. They were added to the topmost peak.

For two days all Beatty, from the leading citizen who sold us our supplies to the Mexican cook in the railroad restaurant who told us that it was so hot in Death Valley the lizards had to turn over on their backs and wave their feet in the air to cool them, had been much cheered by our presence. Nobody expected us to be gone very long and they watched the loading up of the month's supplies with amused interest. When we were ready we had to pose beside the wagon in the middle of the street to have our picture taken. Then somebody cried "Good luck!" and at last we started.

As soon as a turn in the road hid Beatty the silence closed around us. The crisp, clear air made our blood tingle. We walked the first few miles while the Worrier drove. The sun, the wind, and the scarred old mountains became the only important things in the world. We were committed to sunrise and sunset, rocks and brush were to be our companions, lonely springs were to keep us alive, the roots of the greasewood were to warm us, all our possessions were contained in one frail wagon. In half an hour the desert claimed us. The sun that loves the desert clothed it in colored garments.

Previous -- Next

Contents

I. The Feel of the Outdoors

II. How We Found Mojave

III. The White Heart

IV. The Outfit

V. Entering Death Valley

VI. The Strangest Farm in the World

VII. The Burning Sands

VIII. The Dry Camp

IX. The Mountain Spring

X. The High White Peaks

XI. Snowstorm and Sandstorm

XII. The End of the Adventure