The Legend of Willie Boy

by T.C. Wier - Desert Magazine - August 1980

There is something about the California Desert that

prompts men on the run to seek her sanctuary. Joaquin

Murrieta, a Mexican bandito of an earlier time, used

her boulders and ravines to hide from the law

for many months. The infamous Manson Family

headquartered in the desert, as did At Capone, way back

when. Even now, it's a rare year that some desperado

does not flee to her anonymous stretches, hoping

to dodge lawmen on the hunt with horses and 4WDs and,

lately, helicopters. Of all who have sought her refuge,

though, none looms more boldly in our desert lore than

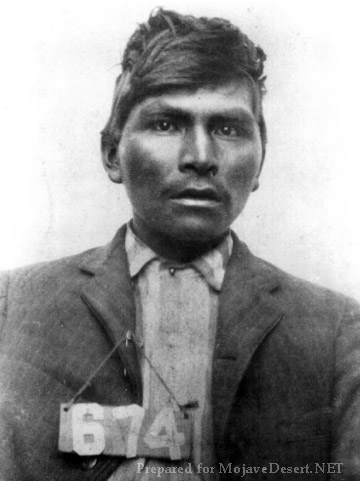

a young

Paiute Indian

called Willie Boy.

Bolstered by stolen whiskey and blinded by his love for a young

Indian girl named Lolita, Willie Boy, on a hot September night in 1909, shot

and killed Lolita's father, and then fled with her into the wilds of the Mojave Desert.

There, armed only with a Winchester rifle, plus a keen knowledge of desert survival,

Willie Boy eluded capture for nearly three weeks. Unmatched in duress to this day,

that sojourn earned for Willie Boy a permanent place in the history of the

California Desert.

Had he not run, but surrendered or been captured at the scene, it is doubtful

the Indian would have been given more than a mention in the local press. Murders

were then, as now, common events and Indians were often afoul of the law. The

killing of an Indian by another Indian in 1909 would have hardly raised an eyebrow,

let alone gain national attention.

But Willie Boy decided to run and men like to chase after running prey, especially

prey that is cunning and dangerous. So when word spread that Old Mike Boniface,

a

Chemeheuvi Indian, had been

shot dead under his own blanket and his daughter

taken captive into the desert, men began to saddle up and load up and move out

in what was to become one of the biggest manhunts in

the history of the Old West,and one of its last.

By 1909 the Old West as we see it today in movies and on television had all but vanished

from real life. More and more, people were becoming citified. They

moved about in motorcars, dressed like dudes, built houses complete with inside toilets

that flushed. Change was in the air, progress ran at full throttle. To try to hold

onto the dying past meant only to die with it.

Then the Willie Boy saga exploded and for one brief moment the Old West was

born again. Men on horseback, with guns and grit and a sense of law and order,

Western Style, arose like phantoms from the past to ride once more across the

open range.

-

Willie Boy was in the truest sense a desert Indian. Born in

Pahrump, Nevada, he migrated with his

family to an oasis at

Twentynine Palms,

California. There he learned to shoot and

hunt and ride a horse with amazing skill.

He was a runner, too, and one of the best

baseball players in Banning, California, an

important desert farming region and the

scene of his treacherous murder of

Old Mike.

As with other Indians of that area, Old

Mike and his people were in Banning to

work the almond harvest. Willie Boy was

working the ranches, too, but his real

reason for being in Banning was because

Lolita was there. He loved her very much.

Marriage, though, was forbidden.

Distantly related, such a union would have

been considered heinous among the

Indians. Willie Boy knew this, but he either

did not agree with it, or felt it unimportant

in light of the love he had for the girl.

He thus ignored Old Mike's warning to

forget his daughter and leave her alone.

Instead, he captured her and took her

away. Marriage by capture, an ancient

custom among Indians of that area, was

rarely practiced in Willie Boy's time. That

he used it clearly showed the lengths he

was willing to go to possess the girl.

When Old Mike discovered his daughter

had been taken by Willie Boy, he quickly

tracked them down and recaptured the

girl. By custom, he would have had the

right to kill Willie Boy, but because of past

friendships, he merely upbraided him and

returned with Lolita to camp. This was his

fatal error. In three months' time, Old Mike

himself would be dead and Lolita would

be, once again, Willie Boy's captive bride.

The California Desert can be a deadly

adversary. Caught beneath her sun without

water or proper covering, she can kill you

in less than a day. Wander too far from road

or house or other landmark, she'll trick

you into vertigo, then bake you to death

while you dig at her sand for water.

Decline to rest in whatever shade she

provides, she'll oblige your foolishness

with a forced march through her burning

hell. Never take the desert for granted,

never think to deal with her on any terms

but hers.

Willie Boy had respect for the desert,

both as friend and as adversary. He had

walked her many times, hunted her game,

drank from her springs, slept upon her

shifting sands. He had been whipped by

her windstorms, broiled by her sun. He

knew the wrath of her winters and the

fierceness of her flash floods, one of which

had swept his own parents to their deaths

when Willie Boy was but a child. He knew

what he could do with her and what he

could not, so he trusted her to help

him escape.

-

The pair were able to gain a good

six hours on any one who chose to

follow them. Fearing death, too,

Old Mike's family had waited that long to

report the killing to authorities. Still, Willie

Boy took no chances. Keeping well out of

sight of the main roads, he made his way

with Lolita through the draws and canyons

that bordered the high deserts, of Morongo

Segundo Chino, an Indian

tracker, was a member of the

posse and a hero of the ambush.

Valley and Yucca. Three days later, they

reached an area called The Pipes. There

Willie Boy risked a campfire to cook a

rabbit he had shot.

Trackers, arriving at The Pipes the next

day, found the campfire still warm.

Encouraged, those who could pushed on,

confident that Willie Boy was just ahead.

He was also in trouble. While his tracks

were steady and sure, it was apparent that

Lolita's were becoming scuff marks in the

sand. She was either resisting or tiring out.

Whatever, her reluctant steps were sure to

slow Willie Boy down. Taking heart in this

knowledge, the men bedded down for the

night, certain this matter with the Indian

would soon be settled.

Having breakfast before sunup, the men

were back on the trail by dawn. Happily, it

read the same as yesterday. Lolita was

holding Willie Boy back. His quarry had

become his snare.

The men grew silent as they gathered at

the top of a ridge and looked down. Only

the careless squeak of saddlery and the

occasional snort of a horse broke the

stillness. At the bottom of the ridge,

sprawled face down across a boulder,

Lolita lay dead, a bullet in her back.

To the men in pursuit, Lolita's murder

was further evidence of Willie Boy's

savagery. A hindrance to him now because

of her fatigue, he had cut her down to save

himself. To the Indian, though", her killing

was an act of mercy, to save her from being

taken by white men. To Willie Boy, Lolita

was his wife. If he gave her up to the white

man, he would, in effect, be giving

up himself.

Regardless of his motive for killing the

girl, her death did spread the distance

between himself and the posse. Not only

could he move more swiftly now, the posse

was forced to turn back for the moment to

bring Lolita home. Thus Willie Boy gained

an extra edge. But had they not returned

with the girl, coyotes would surely have

devoured her.

-

Meanwhile, those hunting Willie Boy

grew from a local constable with a

handful of men to two sheriffs

departments from as many counties, the

Bureau of Indian Affairs, dozens of white

men, several Indian trackers, Banning

Reservation police and wagons loaded with

provisions for several days of desert

pursuit. Dispersed at different times and to

different areas where they thought Willie

Boy might be heading, the manhunt grew

to monumental proportions. With the

murder of Lolita, it also grew into a

grim resolve.

Until Lolita's body was brought back to

Banning, the newspapers had given the

manhunt little attention. With this new

outrage, however, black headlines began to

emerge, exploiting Willie Boy as a mad

killer on the loose. Localized at first, the

story was eventually picked up by the wire

services and soon the whole nation was

following the manhunt. It was as if people

everywhere sensed in this final struggle of

the past to live, an excitement all wanted

to share.

Willie Boy's main concern, though, was

not in headlines but in survival and

eventual escape. He felt that if he could

reach the oasis at Twentynine Palms, his

people would provide refuge, or a horse

and supplies for further flight.

When he reached the oasis, exactly one

week from the night he killed Old Mike, he

found it deserted and stripped of

everything he could have used to aid his

escape. Everyone had fled to the Banning

Reservation for safety, fearing that if Willie

Boy came to Twentynine Palms, he would

kill them all.

Denied their support, Willie Boy's spirit

withered. He glanced about him, appalled

at the devastation he had caused;

remembering, perhaps, happier times

when, as a teenager here, he had had some

hope of a meaningful life. It was gone now,

gone forever. He checked his rifle, counted

his rounds, then turned resolutely back

toward the desert wastes that had so

recently shielded him. Now they were

soon to witness his death.

A full four days after his visit to the oasis,

Willie Boy reached Ruby Mountain where

he decided to make his stand. He found a

natural barricade along the mountain

which gave him full view of anyone who

handcuffs and shattered his hip. He lay in

the open, face up, blood pulsing badly

from his wound.

The men, now under cover, began firing

randomly at the barricade. But only now

and then would Willie Boy fire back. When

one of the Indian trackers dashed away for

help, Willie Boy danced bullets after him,

but always off target. It was peculiar

response from a man fighting for his life.

Peculiar, too, was Willie Boy's decision

to kill the horses instead of the men. He

could easily have gotten them all, taken

one of the horses and what supplies he

approached from below. There was only a

distant willow thicket behind which his

attackers could hide. From this vantage

point, Willie Boy waited and rested and

considered his plight.

After two weeks and 500 miles of

desert torment, he was too tired to

run anymore. But even if he had

the will and strength to go on, where

would he go? And who was there to help

him? He had killed the only thing he loved

and unleashed upon himself, it seemed,

the anger of everyone who knew of his

deed. He had no will to move ahead, or

even think ahead. It seemed the desert had

beaten all of that out of him and left him a

mindless form without the power to

determine any part of his destiny.

The five men who broke from the

willow thicket had but a moment to

evaluate the barricade above them before

Willie Boy opened fire. Dropping one

horse, spooking a second, then dropping

three more, Willie Boy had every man

unhorsed and running for cover before

any of them could draw a gun. It was the

fight all of them had been waiting for, but

not one had been prepared.

During the fracas only one man, the

leader, was shot. The bullet that was meant

for his horse had glanced off the tracker's

handcuffs and shattered his hip. He lay in

the open, face up, blood pulsing badly

from his wound.

The men, now under cover, began firing

randomly at the barricade. But only now

and then would Willie Boy fire back. When

one of the Indian trackers dashed away for

help, Willie Boy danced bullets after him,

but always off target. It was peculiar

response from a man fighting for his life.

Peculiar, too, was Willie Boy's decision

to kill the horses instead of the men. He

could easilyhave gotten them all, taken

one of the horses and what supplies he

needed and made good his escape. With

two murders already against him, why

should he balk at further killings?

To the men who crouched below the

barricade, such restraint seemed illogical.

To Willie Boy, who waited above, it was the

only option he had left, seeing that he was

already dead.

When a man dies, he dies first in his

mind, regardless of how soon or late the

physical death follows. So with Willie Boy.

All he needed was time to earn' out the

physical act. Pinning the posse down

would give him that time.

-

When darkness came, the men'decided to give up the vigil and

take their wounded leader back

down the mountain to medical aid. The

Indian could wait, they surmised. As they

eased the pain-racked man onto the only

surviving horse, a rumble of rocks was

heard from above, then a single shot

cracked through the air.

"He's dead," someone whispered as they

descended. "He's shot himself." But the

men would not wait to find out.

A week was gone before another posse

went back to Ruby Mountain to try to pick

up Willie Boy's trail. The trail, though, went

no further than the barricade. Willie Boy

had, indeed, taken his own life.

So ended the manhunt. So closed an era.

Much was made of the matter. A play was

written and performed to packed houses.

Ruby Mountain was renamed Willie Boy

Mountain. Two sheriffs were re-elected on

the strength of the hunt, a Reservation

superintendent lost her job because of it

and a young reporter made a name for

himself by his coverage of the struggle.

Fifty years were to pass, though, before

any valuable narrative was produced. Harry

Lawton's "Willie Boy, A Desert Manhunt"

(Paisano Press, Balboa Island, Calif., I960)

is a stirring, yet objective account of the

event. From this came the movie, "Tell

Them Willie Boy Is Here," starring Robert

Redford with Robert Blake as Willie Boy.

As for Willie Boy himself? Though the

desert would not give him the life he

bargained for, she did provide him with an

immortality that reached beyond the finite

survival of the flesh. She found a niche for

him in history's walls and placed him there

as she had placed him in the crevices and

crannies of her trackless landscape.

It was a reward he had not sought, an

honor he had not considered the night he

ran to her for hiding. But then, no man on. the run wants any more from the desert

than a place to run and hide. Fame is just

something extra, sometimes thrown in and

sometimes not. ~~~

Desert Magazine - 1980