Panamint

Another product of the search for the Lost Gunsight Mine was Panamint, a boom camp whose mines were first discovered by bandits in 1873, developed by Senator Jones and Stewart in 1874, and on the decline by late 1875.

Surprise Canyon is a secluded steep and narrow canyon tucked between Telescope Peak and the Panamint Valley, some 200 miles from Los Angeles. Originally used as a hideaway, rumors of the Lost Gunsight Mine may have caused the bandits to do a little prospecting while holing up in the canyon. William L. Kennedy, Robert L. Stewart, and Richard C. Jacobs discovered silver here in early 1873. Nadeau places the date as January; Wilson has the three miners organizing their district in February; and Chalfant says it was in April. By June, 80 locations had been filed and ore was assaying at thousands of dollars per ton.

E. P. Raines, after securing a bond on the biggest mines in the area, attempted to publicize Panamint and drum up business for the district. Unsuccessful at first, he later received newspaper publicity by displaying a half ton of ore at the Clarendon Hotel in Los Angeles. There he convinced a group of businessmen, including jewelers, bankers, and freighters, to undertake the building of a wagon road to Panamint. Meeting with success in Los Angeles, he left for San Francisco to meet Senator J. P. Jones, who loaned Raines $1,000, then $14,000 more when they met again in Washington, D.C.

The Nevada senator was a former mine superintendent who became a hero during a fire in 1869 on the Comstock Lode. Jones and his colleague, the distinguished Senator William M. Stewart (also of Nevada) were known as the "Silver Senators" for their wide range of mining investments. The two soon organized the Panamint Mining Company with a capital stock of two million dollars. They spent at least $350,000 in buying up the better Panamint mines.

One particular transaction involved men known to have robbed Wells Fargo on more than one occasion. The good Senator Stewart arranged amnesty for the mine owner, but only after making sure that the owner's profit, some $12,000 was paid to the famous express company to cover their losses. It is highly possible that Stewart's willingness to deal with the bandits persuaded Wells Fargo never to open up an express office in Panamint.

By March, 1874,125 persons called Panamint their home. Panamint City didn't have a schoolhouse, church, jail, or hospital then, nor did it ever. The two senators, due to the lack of an express office, resorted to molding the bullion from their mines into 450-pound cannon balls. In this condition the precious freight could be hauled to Los Angeles unguarded.

On November 28, 1874, the Idaho Panamint Silver Mining Company was organized with a capital stock of five million dollars. The next day the Maryland of Panamint was organized with three million dollars of capital stock. In December seven more Panamint corporations appeared with a capital of forty-two million dollars.

On November 26, 1874, T. S. Harris inaugurated the Panamint News. On December I, he denounced his editor, O. P. Carr, who left town with stolen advertising revenues. Like T. S. Harris and advertisers in the Panamint News, the public who bought shares in Panamint stock would soon wake up and find themselves holding an empty bag.

Panamint had all the indications of being a second Comstock. The mineral belt was 2 1/2 miles wide and 5 miles long. "There is scarcely a mining district where more Continuous and bolder croppings are found than in Panamint," reported C. A. Stetefeldt in 1874. It was indeed true that veins were appearing all over Panamint wide enough to drive a wagon through. The veins could be traced for great lengths, running parallel to Surprise Canyon. Some of the veins were quite fractured, others appeared to be unbroken. The silver ore came in two forms. A rich, purer mineral near the surface, changing with depth to antimoniates of copper, lead, iron, and zinc, with sulphu ret of silver and water. The rich ore assayed over $900 per ton from Stewart's Wonder, $350 dollars per ton from Jacob's Wonder, and $600 per ton from the Wyoming. The more common ore ranged in value from $12 to $85 a ton. Stewart's Wonder, $350 dollars per ton from Jacob's Wonder, and $600 per ton from the Wyoming. The more common ore ranged in value from $12 to $85 a ton.

A year and a half after the original discovery, the mines were still not developed in depth. Companies that were heavily financed bought and opened up mines with no regard as to which were better situated on the veins. There was the Jacob's Wonder, Stewart's Wonder, the Challenge, Wyoming, Little Chief, Hemlock, Harrison, Hudson River (which was bought by the Surprise Valley company for $25,000), Wonder, Marvel, War Eagle, and the Esperanza. Everyone was hoping that wealth to one would be wealth for all.

The winter of 1874 was Panamint's finest and biggest season. The Surprise Valley Mill and Mining Company was shipping it's ore all the way to the coast and then to Europe for final smelting at a profit! Two stage lines opened service to Panamint in November of 1874. Louis Felsenthal's Bank of Panamint was open for business. Lumber sold for $250 per 1,000 feet and 50 structures soon lined either side of Surprise Canyon. Mules and burros were used as transportation in town, the only vehicle in town being a meat market wagon that doubled as a hearse and parade platform. The Oriental saloon was billed as "the finest on the coast outside of San Francisco."

By January, 1875, 1,500 to 2,000 people inhabited Panamint. One of them was George Zobelein, later to become the founder of the Los Angeles Brewing Company, who bought a $400 lot and opened up a general store. In April two more Panamint corporations were offering stock worth eleven million dollars.

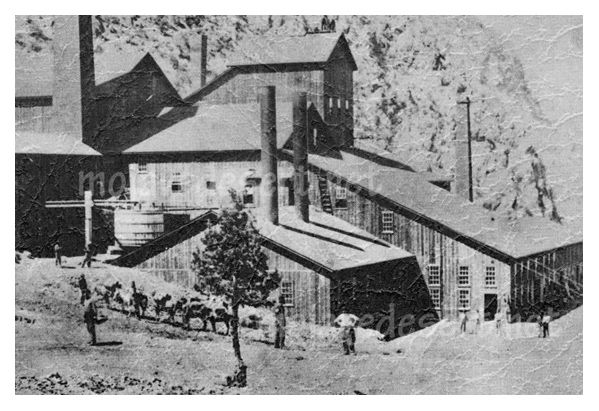

On June 29, 1875 the Surprise Valley Mill and Water Company's twenty-stamp mill went into operation. Ore averaging $80 to $100 per ton from the Wyoming and Hemlock mines traveled down the mountain by means of a 2,600-foot wire tramway to the mill. Wood consumption in the mill's furnace amounted to three cords each day. Each cord cost $12, and miners and mill workers received from $4 to $5.50 a day. The crumbling smokestack of this mill stands in Surprise Canyon. Daniel P. Bell constructed this highly acclaimed mill, but committed suicide in Salt Lake City, Utah on July 26, 1875, being despondent over having contracted cancer.

Panamint's Decline

William Ralston's Bank of California came tumbling down in August, 1875, days after Panamint's twenty-stamp mill began operation. The bank's fall brought down with it much of the Comstock's wealth. With the people's trust and confidence shattered, California hit hard times. People weren't about to speculate. T. S. Harris published his last issue of the Panamint News on October 21, 1875 and left for Darwin, as "the ores there are of a different character-being argentiferous while those here are milling-and consequently the same amount of capital is not required."

In November, 1875, almost everybody had left Panamint for somewhere else. Rumors were circulating that the ore bodies were in danger of exhaustion. Those that were staying were hoping that Senator Jones would come to the rescue.

Panamint has always been waiting for the arrival of cheap rail transportation. Everyone knew the wagon road was only a temporary measure, and that the Panamint mines would exceed the Comstock.

Senator Jones backed the development and creation of the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad. It was grading its right of way in Cajon Pass when on May 17, 1876, William Workman committed suicide. With brother-in-law Francis Temple (who was treasurer of the L. A. & I.), Workman had owned the Workman and Temple Bank. This soon failed, spelling the end for the Los Angeles and Independence Railroad. It's assets soon fell into the hands of competitors and the company silently disappeared.

Less than two months later, on July 24, 1876, a cloudburst washed down Surprise Canyon, carrying a lot of Panamint City with it. The last to give up was Senator Jones himself. In May 1877, "the most serious panic that ever swept over the stock market" caused Jones to shut down his Panamint mill. Jones, like most of the public who poured money into Panamint, wanted to recover his investment at least, if not make a profit. Yet of the approximately two million dollars the "Silver Senators" poured into Panamint, it seems they received little, if anything in return.

Later Revivals

Richard Decker reopened the Panamint Post Office on May 23, 1887, and kept it open until June 19, 1895. Decker and two companions filed a claim January 3, 1890, in Woodpecker Canyon. The mines at Panamint were worked off and on until 1926, and then briefly during 1946-1947. The American Silver Corporation leased 12 patented claims, 4 patented millsites and 42 unpatented claims in the Panamint City area in 1947-1948. Most of the work was concentrated on the Marvel and Hemlock claims. No ore was reported shipped by this company, who built a camp at Panamint and improved the Surprise Canyon road before filing for bankruptcy on March 22, 1948. Throughout the 1970s there has been an increase in activity at Panamint but the veins are elusive and faulting makes them hard to follow.

Panamint City