History of Leadfield

The ghost town of Leadfield has become identified in western mining lore as an example of fraud, deception and deceit at its worst. Located in the middle of Titus Canyon about twenty-two miles west of Beatty, Leadfield boomed briefly in 1925 and 1926. The extensive promotion which surrounded the camp, the unsavory character of its chief promoter, and the swift and sudden demise of the boom has led to unkind treatment at the hands of popular writers of western history. Betty J. Tucker, writing in a 1971 issue of Desert Magazine is a good example:

This town was the brain child of C. C. Julian, who could have sold ice to an Eskimo. He wandered into Titus Canyon with money on his mind. He blasted some tunnels and liberally salted them with lead ore he had brought from Tonopah. Then he sat down and drew up some enticing, maps of the area. He moved the usually dry and never deep Amargosa River miles from its normal bed.

He drew pictures of ships steaming up the river hauling out the bountiful ore from his mines. Then he distributed handbills and lured Eastern promoters into investing money. Miners flocked in at the scent of a big strike and dug their hopeful holes. They built a few shacks. Julian was such a promoter he even conned the U. S. Government into building a post office here.

So goes, the usual, tale, which is fairly well duplicated by most writers of popular lore over the past forty-odd years. The true story, however, is somewhat different. Although Leadfield did set a record of sorts for being one of the shortest-lived towns in western mining history, there was more to it than merely an out-and-out stock swindle. Nor can C. C. Julian be blamed solely for the life and death of Leadfield.

Leadfield, in fact, had ore from the beginning, which was in 1905, not in 1925. During the early days of the Bullfrog boom, Titus Canyon, like most of the territory surrounding the Bullfrog District, was examined by hopeful prospectors. In the fall of that year, W. H. Seaman and Curtis Durnford staked out nine lead and copper claims in the canyon,. and came into Rhyolite with ore samples that assayed as high as $40 to the ton. The prospectors were soon bought out by a consortium headed by Clay Tailman, a local attorney and promoter, and the Death Valley Consolidated Mining Company was incorporated. The company immediately began a development and promotional campaign, and shares of its stock were sold for 2-1/2¢ each.

As usual, the news of the strike stimulated other prospectors and companies to get in on the potential bonanza, and claims were filed for miles around the Death Valley Consolidated property. The Bullfrog Apex Mining & Milling Company, for example, which we have already seen trying to exploit ground near the Original Bullfrog, purchased a group of four claims next to the Death Valley Consolidated. The former company, in the meantime, went to work, and as initial prospects looked encouraging, the price of the stock rose to on the local exchanges.

By May of 1906, the Death Valley Consolidated had progressed far enough to start, taking out its better ore for shipment to the smelters. The company soon realized, however, that the long and arduous trip between its mine and Rhyolite and the high freight rates prevalent between Rhyolite and the far-off smelters, made the shipment of its ore absolutely unprofitable. As a result, the company ceased operations, and after a brief six-month long life span, the Death Valley Consolidated Mining company disappeared.

So matters stood for almost twenty years. Then, in March of 1924, three prospectors named Ben Chambers, L. Christensen and Frank Metts wandered into the canyon and began to stake out numerous claims on some lead deposits which they found. The three men 'worked their claims for over a year, before selling out to a local promoter named John Salsberry. Salsberry had been involved in Death Valley mining since the Bullfrog days, and was a former promoter of several mines on the west side of the valley, including some in the Ubehebe Mining District in the early 1900s, and the Carbonate Mine in the 1910s. Salsberry purchased twelve claims from the three prospectors and a few weeks later formed the Western Lead Mines Company, with 1,500,000 shares of stock worth 10¢ each. Salsberry extended the prospecting work in the district and by the end of 1925 the Western Lead Company had accumulated over fifty claims in Titus Canyon and had started to work. A compressor plant was installed to power the company's air drills, and eighteen men and six trucks began to build a long and steep auto road out of Titus Canyon towards the Beatty highway.

In January of 1926, the company built a boarding house, and began to lay a pipe line from Klare Spring, two miles down the canyon, to the mine site. The young camp was entering the boom stage. Following an enthusiastic Associated -Press report on the new camp, the Inyo County Recorder reported that location notices were pouring into his offices. By January 30th, the town had been officially named Leadfield, and half a dozen mining companies were in operation. Sales of the stock of Western Lead Mines Company were opened on the San Francisco exchange in late January, and within twenty-four hours 40,000 shares had been sold, with the price soaring to $1.57 per share.

Eastern California, and especially Inyo County, was long overdue for a mining boom, and it seemed that the entire county jumped on the bandwagon. Hard times had begun to depress the county's economy, and this new boom was just the shot in the arm which the local merchants had been waiting for. Likewise, Beatty, on the other side of the state line, began to experience a' revival in its economy, and the small railroad town, which had barely eked out an existence since the collapse of the Bullfrog boom, found itself as the new supply metropolis for the miners and companies swarming into Leadfield. No one was willing to look this gift horse in the mouth, and no one questioned the reality of the new boom--to do so would mean a swift ride out of town on a pole as a "knocker."

Then, in early February, came the announcement which seemed to assure the future of Leadfield. C. C. Julian, the "well known oil promoter of Southern California, who had been much in the limelight of late years on account of his spectacular oil operations," had bought into the Western Lead Mines Company, and was its new president. With the backing of such a successful and skilled promoter, Leadfield seemed assured of obtaining the necessary financial support to take it from a prospecting boom camp into a producing mine town. The Inyo Independent greeted the arrival of Julian with a glowing description of his character and abilities. "Julian is recognized as one of the greatest promoters of the country and it is a certainty that with his enthusiastic backing that something will come of Leadfield if there is anything there. Quite a different endorsement would be printed in later years, after the mines had folded and everyone was looking for a scapegoat.

The boom was now on in earnest. During February, the Western Lead Company was reported to have a hundred men working in its mines and on the Titus Canyon road, and talk of building a 500-ton mill was heard. When the road was completed in late February, a steady stream of trucks began entering the canyon, carrying timber, machinery and supplies. The Western Lead Company expanded its payroll to 140 men, and at least six other companies were engaged in serious mining. Average values in the tunnels of the Western Lead Mine were 8% to 30% lead, with seven ounces of silver to the ton, more than enough to make the mine a paying proposition if the ore held out as exploration continued.

The California State Corporation Commission, however, was not so impressed with the company, which had failed to secure a permit before it began selling shares of stock. Rumors of investigations by the Commission raised the righteous indignation of local folk, who refused to allow anyone to try to prick their balloon. The local attitude of Inyo County was well summed up by the Owens Valley Herald

. . . the State Corporation Commission is using its every endeavor to try and prejudice the people against this latest promotion of Julian's. This commission has never sent a man into the Leadfield district to look it over, and it would appear that the stand they have taken is purely spite, just because Julian at one time refused to be dictated to by arrogant members of that Commission. The Commission does not seem to realize that in the stand they are taking that they [are] trying to hinder the development of the resources of this State, and the Commission also does not seem to realize that such arbitrary methods have no place in any development anywhere.

After all, the paper pointed out, Julian was not trying to swindle anyone. He had started a promotional campaign with full-page advertisements in the Los Angeles papers, but he clearly underlined the risks involved. "In the advertisements that he has recently been running in Los Angeles papers he has told in plain words just what he thought of the proposition and has advised people who could not afford to take a gamble not to buy any stock in it--for, as is well known, all mining development is a gamble." In addition, Julian had publicly invited any reputable mining engineer in the world to make a visit to the Leadfield District. If he did not find conditions as stated by Julian, then all expenses of his trip would be paid. In spite of the interference by the Corporation Commission, the paper concluded, "the future of Leadfield seems very bright, and it would not be at all surprising if the mines there did not turn out to [be] the biggest lead producers that the world has ever known." This Inyo County newspaper, obviously, reflected the attitude of the citizens--they desperately wanted and needed a mining boom, and the last thing they wanted was the over-zealous interference of the State of California.

As the paper could well have pointed out, Julian was far from being the only promoter singing the praises of the Leadfield District, for numerous other companies were also trying to cash in on the boom. Such companies, by March of 1926, included the Leadfield New Roads outfit, presided over by Walter J. Frick, who announced that his company had good shipping ore in its tunnels, and would begin regular ore shipments soon. This company had just built a mine office on its property, and was bringing in additional machinery in order to rush the development work. Other companies in business included the Burr-Welch, the Leadfield Carbonate, the Joplin and the Joplin Extension companies, the South Dip mine, the Leadfield Metals, the Last Hope, the Cerusite, the Sand Carbonate and several others. There was, of course, a company called the Western Lead Extension, in the best traditions of mining booms.

But the Western Lead Mines Company, Julian's pet, was leading the pack. It was forging ahead with its development work, with one of its tunnels six hundred feet inside the mountain. The company purchased a 180-horsepower Fairbanks-Morse diesel engine in March, as well as a second air compressor to power its machine drills. The town of Leadfield was also trying to keep pace with the boom, which was attracting miners from all over the country, and announced that a large hotel would soon be built. The cosmopolitan nature of the boom was emphasized in early March, when eighteen former Alaskan miners sat down in Leadfield for a reunion dinner.

Then on March 15th, came the day which put Leadfield on the map, when the first of Julian's promotional excursions pulled into Beatty. A specially-chartered train pulled into the sleepy town on Sunday morning and disgorged 340 passengers, who had been chosen from among the 1,500 who applied for the trip. Together with another 840 visitors from Tonopah and Goldfield, the entourage overwhelmed Beatty until loaded into ninety-four automobiles for the trip through Titus Canyon into Leadfield.

After bumping over the spectacular new road and down into Leadfield, the visitors were served a sumptuous outdoor feast by the proprietor of the local Ole's Inn, who reported that he dished up 1,120 meals. The dinner was served to music provided by a six-piece band imported from Los Angeles. Lieutenant-Governor Gover of Nevada gave the key-note speech, ridiculing the persecution of Julian by the California Corporation Commission, and praising Julian for overcoming the numerous obstacles which modern governmental bureaucracies put in a man's path. Several other speeches followed, including one by Julian, voicing much the same opinion. During the afternoon the Tonopah orchestra played for those who wished to listen or dance (twenty-four women had come on the train), and the more serious visitors were conducted on a tour of the Western Lead Mine by John Salsberry. The mine, said Salsberry, was still in the early stages of development, but more serious work would get under way with the arrival of over $55,000 worth of machinery which the company had recently ordered. The visitors were then driven back to Beatty for another night of partying, before going home. The trip, obviously, was a big success, and Western Lead stock advanced 25¢ on the San Francisco market the next day.

The Leadfield boom was now in its height. Plans were announced to build a forty-room hotel, and a week after the grand excursion the town had its own newspaper, the Leadfield Chronicle By the end of the month of March, Western Lead stock had soared to $3.30 a share, and over 300,000 shares in the company had been sold. In addition to the general public, ore buying and smelting concerns were becoming interested in the camp, and several sent representatives to the district to discuss reduction and smelting rates. The Tonopah & Tidewater Railroad, eager for more business, also sent representatives to Leadfield, in order to estimate the amount of ore which the mines might be sending over its tracks.

In the months following the great train excursion, Leadfield continued to develop. More companies, including the Western Lead Extension, were given permission to sell their stocks on the exchanges of various states, and several, including the New Roads Mining Company, began to sort their high-grade ore for shipment. Salsberry, manager of the Western Lead Company, announced plans to build a 400-ton concentration plant at Leadfield, and new'" mining companies, such as the Western Lead Mines Number Two, opened for business. Since it cost $18 per ton to haul ore from Leadfield to the railroad terminal at Beatty--which prohibited the shipment of most of the ore--local operators began to call for an extension of the railroad to Leadfield. The Tonopah & Tidewater, however, coldly replied that definite "plans for building a railroad spur into Leadfield have not been made, as present business does not warrant its construction."

Next page

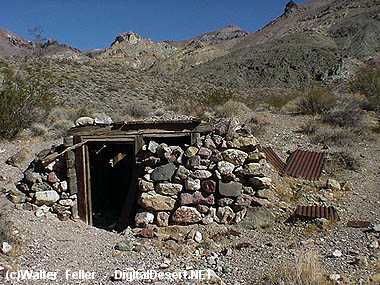

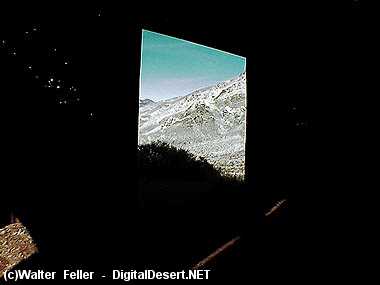

Photos - Walter Feller

Source - Death Valley NP: Historic Resource Study - Linda Greene