The Funeral Mountains - Inyo Mine

Like the Hayseed Mine to the east, the Inyo Mine on the Echo side of the district represents both the earliest discovery on the west side of the Funeral Range, and also the only mine on that side which ever produced more than an occasional sack of gold. The first locations in Echo Canyon were made by Maroni Hicks and Chet Leavitt in January of 1905. After a brief trip to civilization for supplies, the two men returned to Echo Canyon in March, and made several more locations. By May of 1905, the prospectors had accumulated two groups of locations, consisting of twenty claims, and after staking out all the ground which they thought might be any good, they started to dig a tunnel on one of the claims in June.

During the summer of 1905, as the first movements into the Echo-Lee District began, the Hicks and Leavitt property became one of the most talked about in the region. It appeared that the prospector's dream was about to come true for the two men, as they found capitalists interested in purchasing their locations. In August, nine of their claims were bonded to Tasker L. Oddie for $150,000, and the remainder to Charles Schwab for $100,000. Schwab was to pay the prospectors $5,000 on September 1st, if he decided he wanted the mine. Oddie, in turn, was to pay $5,000 on December 1st and the balance of the money one year later. Although Schwab never paid, and apparently never tried to develop his portion of the mine, Oddie's men went to work at once. Soon they had a shaft 50 feet down in the ground, and were talking of erecting a mill, a wire rope tramway and an electrical power plant for the mine. Oddie also considered cutting a new wagon road to Rhyolite at a cost of $1,500, cutting off thirty-five miles from the present winding road.

But by November, Oddie had let his option expire, due to "a misunderstanding having arisen concerning terms, etc.," and the claims were bonded again, to two Colorado capitalists. The new agreement called for a payment of $10,000 immediately, and another $140,000 during later months. But again, the new purchasers were either not impressed when they began to work, or were not able to raise the $10,000 demanded by Hicks and Leavitt, for their option was soon cancelled.

Finally, in December, a sale was made. L. Holbrook and associates, a group of Utah mining promoters, purchased the entire mine and incorporated the Inyo Gold Mining Company. Maroni Hicks accepted cash for his half of the mine, but Chet Leavitt retained his interests and became the vice president of the new company. The Inyo Gold was incorporated in Utah, with a capitalization of $1,000,000, based upon 1,000,000 shares of stock with a par value of $1 each. The new company owned twenty-one claims, which represented all of the Hicks & Leavitt properties, including those which had formerly been bonded to Charles Schwab. Soon after the incorporation of the new company, development work in the mine began, and in early January of 1906, the property was surveyed.

By the first of February the shaft on the Inyo Mine was down to sixty-five feet, and that depth had been increased to 100 feet by March. At that time, nine men were employed at the mine, under the direction of Chef Leavitt, who was general manager of the company. By the end of April, crosscuts were going out from the W0-foot level of the shaft in the search for ore, and a second shaft was started on another claim. In June, a big strike was made at the mine, as noted by the Rhyolite Herald "The Inyo Gold Mining Company has made the most phenomenal strike in the history of Funeral Range mining and one of the biggest uncoverings since the discovery of Tonopah Assays from the new strike, which was at the bottom of the new shaft at a depth of sixty-five feet, were close to $300 per ton."

Following the news of that strike, which seemed to prove that the Inyo Gold would make the transition from a developing to a producing mine, rumors began to circulate concerning the sale of the property. In August, the Bullfrog Miner reported that the mine had been sold to the Schwab interests for $2,000,000, and the Rhyolite Herald reported that all of the company's stock had been sold for $1 per share to a group of Salt Lake City capitalists. But nothing came of either rumor, and since the mine ceased work during the hot summer months, little was heard from it.

In October the Inyo Gold Mining Company was reorganized, although the changes were mostly internal. L. Holbrook, the principal owner, was still listed as president of the company, but Chet Leavitt lost his position as vice president. Work would be resumed shortly, the company stated, and now that the railroads were reaching Rhyolite, the shipment of medium grade ore from the mine would soon make it a producer. But work progressed more slowly than the company had hoped, and no shipments were made in 1906, although the company had its new shaft down to seventy-three feet by the end of that year, and several crosscuts were started.

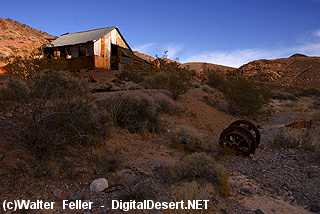

But as 1907 opened, work began in earnest on the Inyo Gold. The company ordered a small gas hoist in early January of that year, and by the end of that month reported that it had three shafts exploring for ore at depths of 100, 73 and 30 feet, respectively. In addition, tunnels and crosscuts were being driven, and ore bodies were being found, although the estimated extent and content of the ore finds were not greatly publicized. Chat Leavitt, who was still the mine superintendent, was employing twenty men in February, and a boarding house had been built at the property for their convenience, Plans were also in the works to construct a commissary store, and the company ordered ore cars and tramway tracks to facilitate the removal of ore from the mine.

Towards the end of February, the Rhyolite Herald took time out to describe and assess the Inyo Gold's property. Average values in the various shafts and tunnels, the paper stated, were around $44 to the ton. The ore was free milling, which meant that it could be treated in the simplest manner, and once the Ash Meadows Water company had completed its pipe line into the Lee district, the company was considering the construction of a mill. Water was now hauled from Furnace Creek, a distance of eight miles, at considerable expense to the company. The boarding house at the mine was feeding thirty miners. Since that overcrowded its accommodations, a new boarding house with an eighteen by thirty foot dining room and a fourteen by sixteen foot kitchen was being built. When it was finished the present boarding house would be converted into a rooming house. In addition, the company was building a sixteen by twenty foot commissary for the sale of groceries and mining supplies to the company's employees and other prospectors in the area. "The concensus of opinion, concluded the Herald "is that the Inyo Gold Mining company's property, the original Hicks & Leavitt group, is one of the most likely properties in the new gold fields along the Nevada-California border."

During March and April, work continued steadily, and the local papers faithfully reported the progress made in the company's shafts and tunnels. By mid-April, the company had begun preparations for the construction of a mill, and several loads of lumber were on the ground. The mill was to be built at the mouth of the main tunnel, near the new blacksmith shop. Thirty men were employed at the mine, and most were eating at the recently-completed boarding house, run by Mr. and Mrs. McKnight. By this time a portion of the mine's new hoisting machinery had arrived, and the company announced that it would not ship its high-grade ore, but would rather keep it on the dump until the mill could be built. In response to several inquiries, the papers reported that the Inyo Gold was a closed corporation, so that the company's stock was not being sold on the open market. Several blocks of shares, amounting to no more than 50,000, had been sold by one or more of the original incoporators of the company, but most of those had been bought back by other owners.

Once again, due to the heat of summer, work slacked during the hot months of 1907. Some miners continued to labor in the shafts and tunnels, but not with the pace of previous months, and the papers had little more to report other than the statistical advances of that work. But in September, the company, which was running out of development funds advanced by the owning partners, decided to go public. From its application for a license to sell stock in California, many details of the company's position are available. Fifty-two thousand of the 300,000 shares of treasury stock in the company had already been sold, and the Inyo Gold was now asking permission to sell the rest. The company had an indebtedness of $15,250 and no money in the treasury. The property was equipped with a hoisting whim, a blacksmith shop, a bunk house, and mining tools, and its employment roll had shrunk to seven men. Three hundred and fifty feet worth of shaft work had been done, in addition to 700 feet of tunneling and 75 feet of crosscutting. No ore shipments had been made, but the company claimed to have $650,000 worth of ore in sight. At the time of its application, the Inyo Gold had already been approved for stock sales in Utah.

The Inyo Mine could not have chosen a worse time to go public, for the Panic of 1907 hit the district shortly after the company put its stock up for sale. Had the decision been made six months earlier, the Inyo mine could have taken advantage of the height of the Echo-Lee District boom, when stock in much less worthy mines was selling at fever-inflated prices. Now, in the fall of 1907, mines were closing and very few investors could be found who were willing to risk scarce investment funds in an outlying district. Now, instead of a fat treasury which would have enabled the company to continue its development work on an extensive scale, and to build its mill, the Inyo Gold instead was faced with bankruptcy.

Nevertheless, the company continued operations for a few months. Work was continued during September and October, with a force of between fifteen and twenty miners. But after the middle of October, momentum slowed considerably and very little further work was accomplished for the rest of 1907, although the mine was reported to still be employing a "small force of men" at the end of the year. The Rhyolite Herald denied rumors that the Inyo had closed down completely in December, and went on to lament the general state of mining in Echo canyon. "The properties are among the best in the district and it is much regretted that the companies do not find it consistent to work on a large scale. But the ore is there and when the financial sky is clearer, the properties will show the world what kind of golden lining Echo canyon is made of."

Next >