Prescott to Los Angelos

CHAPTER XXVILeaving Prescott

Prescott, Arizona

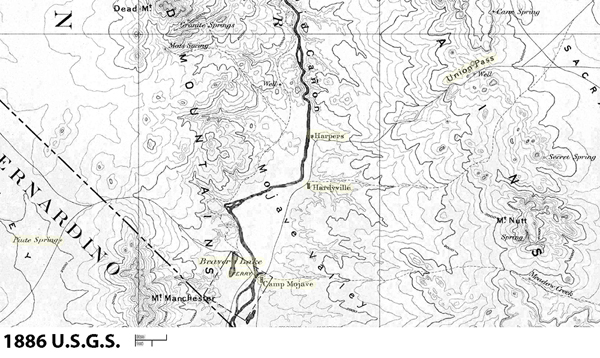

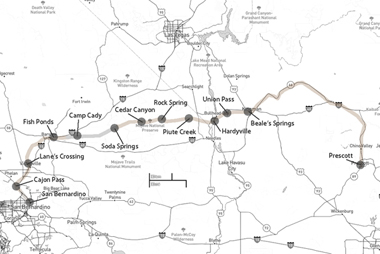

Prescott, as already intimated, was not Paradise, and we left there April 13th, for Los Angelos, via Hardyville and Fort Mojave, on our return "inside," with real rejoicing. Our first stage was to Fort Mojave, on the Colorado, distant one hundred and sixty miles, and this we made in five days. Of course, we travelled by ambulance, and "camped out" every night, as elsewhere mostly in Arizona. The road was a toll-road, but its general condition was hardly such, as to justify the collection of tolls ordinarily. As a whole, it was naturally a very fair road, though there were some bad points, as at Juniper Mountain and Union Pass, where considerable work had been required to carry the grades along. At Williamson's Valley, twenty miles out from Prescott, we found one of the best agricultural and grazing districts, that we had yet seen in Arizona. There were but two or three settlers there then, though there were apparently several thousands of acres fit for farms. The hills adjacent abounded in scattered cedars and junipers, that would do for fencing and fuel, and game seemed more abundant near there, than in any place we had yet been. Quails, found everywhere in Arizona to some extent, here soon thickened up; the jack-rabbits bounded more numerously through the bushes; even pigeons and wild-turkeys were heard of; and as we[Pg 410] rattled down through a rocky glen, at the western side of the valley, a herd of likely deer cantered leisurely across the road—the first we had seen in Arizona, or indeed elsewhere in the West.

Westward

Beale's Springs

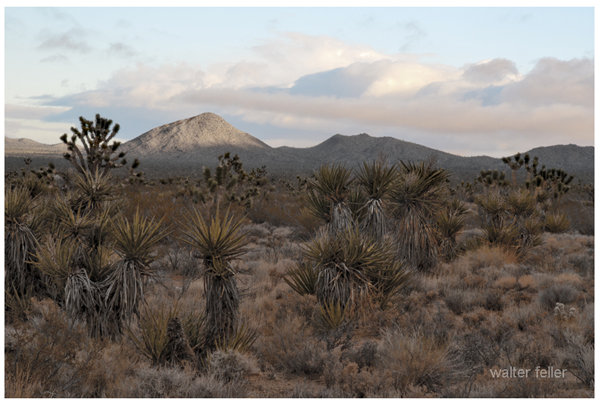

Thence across Juniper Mountain to Rock Springs, some fifty miles, the country was wild and desolate, with a scraggy growth of cedars and junipers much of the way. A few scattered oaks and pines grew here and there, but they could scarcely be called good timber, or much of it. At Rock Springs was a fine bottom of several hundred acres, but not a single inhabitant. Thence on to Hardyville, through Cottonwood Cañon, past Hualapai Springs, Beale's Springs, etc., for nearly a hundred miles, there were no ranches, and no cultivable lands, indeed, worth mentioning. The country, as a whole, seemed a vast volcanic desert—of mountains, cañons, and mesas—and what it was ever made for, except to excite wonder and astonishment, is a mystery to the passing traveller. Even at the high elevation we were travelling, usually four or five thousand feet above the sea, the sun was already intensely hot by day, though the air grew bitingly cold at night, before morning. The principal growth, after leaving Rock Springs, was sage-brush and grease-wood, and in many places it proved difficult to secure sufficient for fires of even these. Water was found only at distances of ten and twenty miles apart, and in the dry summer months it must be still scarcer. Our poor animals suffered greatly, and one day we came near losing several—two of them continuing sick far into the night. Now and then we found an Indian trail crossing the road, but the Red Skins either did not see us, or else kept themselves well under cover, intimidated by the half-dozen cavalrymen, that accompanied us as escort.

Union Pass

The prevailing hues of the landscape were a dull red[Pg 411] and brownish gray, and these produced at times some very singular and striking effects. The one thing, that relieved our ride from utter dullness and monotony, was the weird and picturesque forms, in which nature has there piled up her rocks, and chiseled out her mountains. Domes, peaks, terraces, castles, turrets, ramparts—all were sculptured against the cloudless sky; and we fell to interesting ourselves sometimes for hours, as we rode along, in tracing out the strange resemblances to all sorts of architecture and animals, ancient and modern, that nature, in her silent sublimity, has perpetrated there. At sunset, when parting day lingered and played upon the surrounding or distant mountains, it bathed their rock-ribbed sides and summits in the most gorgeous tints of purple and maroon, and filled the imagination with all that was most sublime and mysterious. What Milton must have thought of in portraying Hell, or Dante imagined in delineating the weird and sombre landscapes of his awful Inferno, may well be realized in passing through this singular region, where Desolation seems to have outstretched her wings, and made up her mind to brood gloomily forever.

El Dorado Cañon

Union Pass

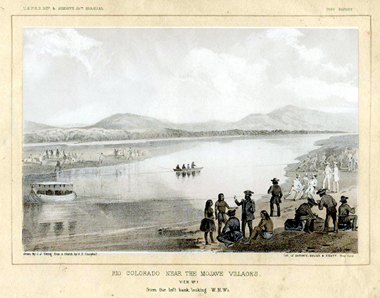

At Union Pass, we crossed the last mountain range, at an elevation of fully five thousand feet, whence we caught welcome sight again of the ruby waters of the Colorado. Debouching into the valley, we presently struck the river at Hardyville. Here it winds its sinuous course, through a broad valley of volcanic mesas and mountains, and has no bottoms worth mentioning, except those occupied of old by the Mojave Indians. These are fertilized by the annual overflow of the Colorado, like the bottoms of the Nile, and no doubt might be made to produce very largely. As it was, the Mojaves scratched them a little, so as to plant some corn[Pg 412] and barley, and raise a few beans, vegetables, etc., the surplus of which they sold chiefly at Hardyville, for Mr. Hardy to re-sell to the Government again—of course, at a profit. It seemed, on the whole, that they did not usually raise enough, off of all their broad acres, to feed and clothe themselves comfortably; and we were told they would often go hungry, were it not for the gratuitous issues of flour, meal, and other supplies occasionally made to them by the commanding officer at Fort Mojave. We rode through their villages one evening, while halting at Fort Mojave, and found they numbered about a thousand or so just there; but farther down the Colorado, at La Paz, there was said to be another branch of them, even more numerous. They were usually a shapely, well-made race, and seemed to take life even more easy, if possible, than their red brethren elsewhere. Their women made a rude pottery ware, that seemed in general use among them, and the men themselves sometimes labored commendably, in gathering drift-wood for fuel for the petty steamers, that occasionally ascended to Hardyville. These Mojaves had been quiet and peaceable for years, and it seemed very moderate efforts would put them on the road to civilization, as readily as the Choctaws and the Cherokees. But they complained, and quite justly, that the Government did not furnish them implements, tools, seeds, etc., to enable them to work their lands and support themselves, while the savage Hualapais, Pai-Utes, and other hostile tribes, were being constantly bribed with presents and annuities. This, however, was only another instance of the stupidity and blundering of our Indian Department at that time, whose policy, or rather impolicy, seemed to be to neglect friendly Indians, and exhaust its money and efforts on hostile ones, under the plea of[Pg 413] "pacifying" them! As if "gifts" and "annuities" ever really pacified or civilized a Red Skin yet, or ever will! No; the only true policy with our Indians, then as now, is to encourage and reward the friendly, in every right way; while the hostile ones should be turned over to the Army, for chastisement and surveillance, to the uttermost, until they learn the hard lesson, that henceforth they must behave themselves.

Fort Mojave

Fort Mohave

Fort Mojave, some four miles or so below Hardyville, on the east bank of the Colorado, was a rude post, most uncomfortable every way. It had been established originally in 1860, abandoned in 1861, but re-occupied in 1864, and maintained since then. We found it hot, and dusty, and miserable, even in April; and could well imagine what it must be in July and August. At Prescott, we were some six thousand feet above the sea; but here we had got down to only about eleven hundred, and the change was most perceptible. Here were a handful of troops, and two or three officers, all praying for the day when they might be ordered elsewhere, assured that fortune could send them to no worse post, outside of Alaska. One officer had his wife along, a lady delicately bred, from Pittsburg, Pa., and this was her first experience of Army life. When we first arrived, she tried to talk cheerily, and bore up bravely for awhile; but before we left, she broke down in tears, and confessed to her utter loneliness and misery. No wonder, when she was the only white woman there, no other within a hundred miles or more; and no newspaper or mail even, except once a month or fortnight, as things happened to be.

click map for larger size.

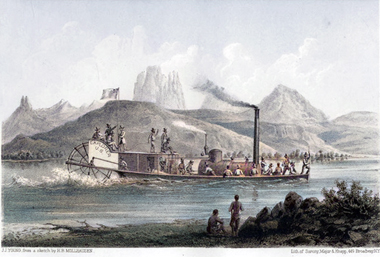

Hardyville itself was then more of a name than place, consisting chiefly of a warehouse and quartz-mill, with a few adobe shanties. Near Hardyville, some ten or twenty miles away in the outlying mountains, there[Pg 414] were several mines—gold, silver, and copper—of more or less richness, and the mill was located here to take advantage of the two great essentials, wood and water. The mill, however, was standing idle, like most enterprises in Arizona, and but little was doing in the mines. Mr. Hardy himself, a hard-working energetic man, and the Ben Holliday or Gen. Banning of that region, controlling all its business, including Government contracts, from the Colorado to Prescott and beyond, was getting out some ore, and specimens we saw at his store were certainly very handsome. He said there were "leads" in the neighboring mountains of exceeding richness, and indeed here and at other similar points along the Colorado, as at La Paz, Aubrey City, El Dorado Cañon, etc., there seemed the best chances for mining of anywhere in Arizona. Here were wood (drift-wood, in which the Colorado abounds) and water, the two great needs, usually wanting elsewhere in Arizona; and the Colorado itself, it would seem, ought to afford reasonably cheap and quick transportation, if the steamboats on it were constructed and run with proper enterprise and efficiency.

Colorado River

Colorado River

Colorado RiverThe great drawback to Arizona then, overshadowing perhaps all others, not excepting the Apaches, was the perfectly frightful and ruinous cost of transportation. To reach any mining-district there from California, except those along the Colorado, you had to travel from three to five hundred miles through what are practically deserts; and for every ton of freight carried into or out of the Territory, you were called on to pay from three to five cents per pound, per hundred miles, in coin. Golconda, itself, could not flourish under such circumstances, much less Arizona—which is scarcely a Golconda. The patent and palpable remedy for all this, was either a railroad[Pg 415] or the speedy and regular navigation of the Colorado. It seemed nonsense to say that the Colorado could not be navigated, and that too at rates reasonably cheap. It looked no worse than the Ohio and the Missouri, and like western rivers ordinarily; and there appeared but small hope for Arizona very speedily, until she availed herself to the full of its actual advantages. With the alleged mines along the Colorado, from Ft. Yuma to El Dorado, in good operation, her population, as it increased, would naturally overflow to other districts; and, in the end, arid Arizona would become reasonably prosperous. But, like all other commonwealths, she must have a base to stand on and work from. That base seemed naturally and necessarily the Colorado River, indifferent as it was. And all attempts to develop herself, except from that, in the absence of a railroad, seemed likely to end like the efforts of the man, who tried to build a pyramid with the apex downward. History declares it was not a "success."

Bidding Goodbye

Camp Rock Spring

Bidding good-bye to our friends at Fort Mojave, we crossed the Colorado on a rude flat-boat, on the evening of April 18th, and proceeded three miles to Beaver Lake where we camped for the night, in order to get a good start next day. We dismissed our escort at Fort Mojave, as no longer necessary; and, Gov. McCormick and wife having left us at Prescott, our little party was now reduced to two and our drivers. Col. Carter, Secretary of the Territory, had accompanied us from Prescott to Mojave; but here he left us for a trip up the Colorado, intending to push into the Big Cañon, if possible. Subsequently, I learned, he failed in doing this; but the fault was not his, and, for the present, we bade him speedy success and a safe return.

Desert Crossing

Soda Lake

From Fort Mojave, on the Colorado, to Los Angelos was still about three hundred miles, and this we accomplished[Pg 416] in eight days. The valley or great basin of the Colorado extends most of the distance, and of the intervening country, as a whole, the most that can be said of it is, that it is an absolute desert of extinct volcanoes and outstretched sand-plains, fit only for tarantulas and centipedes, rattlesnakes and Indians. As far as could be seen, I think this a fair and truthful statement of pretty much all that region to Cajon Pass, and don't see how it can well be objected to, by any honest mind. Its changes of elevation are, indeed, something very curious. At Fort Mojave, on the banks of the Colorado, you are only about a thousand feet above the sea. Thence, for ten or twelve miles, you steadily ascend, until you get where the view of the Colorado Valley proper becomes something really sublime—a barren ocean, a sea of desolation, with a line of living green meandering through the centre—and at Pai-Ute Hill, only some thirty miles from the Colorado, you reach an elevation of some four thousand feet. At Government Holes, indeed, you get up to 5,204 feet; but at Soda Lake, about a hundred miles from Fort Mojave, you descend again to 1,075 feet, or seventy-four feet lower than the Colorado itself.[23] From here you climb back to 1,852 feet at Camp Cady, some forty miles from Soda Lake; 2,678 feet at Cottonwood Ranch, some eighty miles from Soda Lake; and gradually get up again to 5,000 feet at Cajon Pass, about one hundred and twenty miles from Soda Lake. These ascents and descents usually are not sudden, nor indeed much perceptible; but gradually you roll up and down over a vast desert region,[Pg 417] where the sun was already (in April) intensely hot by day, and getting to be fairly warm at night.

Paiute Creek

Desert Crossing

In the long drives by day, sometimes forty and fifty miles—to reach water—the heat and glare from the sand became terrible to the eyes, and twice we drove all night, lying by in the day, to avoid this. By day, we usually saw no live thing, except here and there a stray buzzard, or scampering lizard, or horned toad. By night, we would hear the rattlesnakes hiss and rattle, as we drove along—our "outfit" as we rattled by, I suppose, disturbing their quiet siestas, or moonlight promenades. It was too early in the season, however, to be troubled much with such interesting acquaintances as rattlesnakes, tarantulas, centipedes, etc. They were but just beginning to come out of their holes, and we were glad to escape from the country before they ventured forth much. We saw, indeed, some centipedes, and killed several rattlesnakes. One night one of the party woke up, and found something reposing snugly on the outside of his blankets. Giving it a kick and sling from underneath, it proved to be a snake, and answered him back from the place where it landed, with the usual inevitable hiss and defiant rattle. Another night, at Soda Lake, while sleeping by the rocks there, a rattlesnake crawled under the bottom blankets, and in the morning when the owner of them began to yawn and stretch himself, preparatory to getting up, his snakeship from beneath hissed, and rattled, and protested, as badly as a northern copperhead or a southern rebel at the Proclamation of Emancipation, or the Reconstruction measures of Congress. Of course, we all slept on the ground every night, ex necessitate; but, after this, we usually retired with all our clothes and tallest boots on!

Cedar Canyon

Pai-Ute hill, so-called (before spoken of), is really a[Pg 418] sharp and ugly little mountain, up which we toiled slowly and wearily. In rounding an angle of the road, soon after beginning the ascent, one of our ambulances sliding struck a rock, and soon like the famous "One Hoss Shay," ended in a "general spill!" There could hardly have been a more thorough collapse of spokes and felloes—everything seemed to go to pieces—and it could hardly have occurred in a worse place. It was a wild and desolate cañon, barren and rocky, miles away from every human habitation; yet there was nothing for it, but to leave the driver in charge, and the rest of us proceed on to Camp Rock Springs, whence we sent an army-wagon back to gather up the remains and bring them on. Camp Rock Springs itself was a forlorn military post, consisting of one officer and perhaps a dozen men, guarding the Springs and the road there. The officer was quartered in a natural cave in the hillside, and his men had "hutted" themselves out on the sand the best they could. No glory there, nor much chance for military fame; but true patriots and heroes were they, to submit to such privations. Too many of our frontier posts are akin to this, and little do members of Congress east, who know only "the pomp and circumstance of glorious war," imagine what army-life out there really is. It is a poor place for fuss and feathers, gilt epaulets and brass buttons; and our "Home Guard," holiday Militia east, so fond of parading up and down our peaceful streets, with full rations and hotel quarters, would soon acquire for soldiering there only a rare and infinite disgust. Yet these are the nurseries of the Army, and from such hard schools we graduated a Grant and Sherman, Sheridan and Thomas.

Soda Lake

Soda Lake

Soda Lake, already mentioned, is simply a dried-up lake, or sea, whose salts of soda effloresce and whiten the[Pg 419] ground, like snow, for miles in every direction. The country there is a vast basin, rimmed around with desolate hills and mountains, and during the rainy season a considerable body of water, indeed, collects here. Soon, however, evaporation does its work, and the Lake proper subsides to little or nothing, worth speaking of. When we were there, it was said to be twenty miles long, by four or five wide, though of course everywhere very marshy or shallow. Skirting the borders of it, we reached a rocky bluff on (I think) the northern shore, and there found a noble spring of excellent water, welling up of from unknown depths, within a stone's throw of the soda deposits. Here was the usual halting-place, and as we had driven all night, we went into camp on arriving there, soon after sunrise. It was Sunday, April 21st; there was no house or even hut there; no person or living thing; and what with the heat, and glare, and awful desolation—our weariness, fatigue, and sense of isolation—I think it was about the most wretched and miserable day I ever spent anywhere. To crown all, during the night before, while jogging along, we had descried what we supposed to be an Indian camp-fire, off to the south of the road some distance; we had driven quietly but hastily on, getting the utmost out of our jaded mules; but whether the Red Skins were asleep, or had discovered and were now dogging us, awaiting their opportunity, we were blissfully ignorant. We passed the hours away, as best we could, sleeping and watching in turn; but the next morning, bright and early, we were up and off for Camp Cady. We would have departed, indeed, by night; but the route lay largely up the disgusting cañon of the Mojave, and was impracticable in the dark. This was the only sign of hostile Indians we saw en route from the Colorado. We could hardly call it[Pg 420] a genuine "scare;" and yet were not greatly grieved, when we found they had given us a wide berth.

Soda Springs

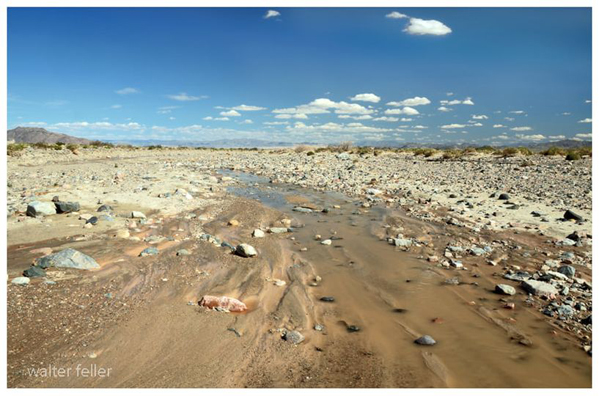

Mojave River

Some fifteen or twenty miles beyond Soda Lake, we struck the Mojave River, so-called, which there runs for several miles through a narrow and rocky cañon, much similar to that of the Hassayampa, though its walls are not so high. The road itself leads up this cañon, for lack of a better route over and through the mountains there, and on first view, it promised to be the Hassayampa over again; but, fortunately, the bottom is chiefly gravel and rock, and therefore has not the same disagreeable habit of "dropping out," when you venture over it. We found from one to two feet of water in the Mojave here, and crossed it, I suppose, at least thirty or forty times between there and Camp Cady—within say twenty miles. Two days afterward, when we crossed it for the last time, farther up, at what is called the Upper Crossing of the Mojave, we found it two feet deeper than it had been a hundred miles below, and with more than twice the volume of water. Our famous Pathfinder, in one of his great expeditions, struck it near here, at freshet height, and it is said reported the Mojave as "an important tributary of the Colorado, navigable for light-draft steamboats several months in the year." He would have been partly right, perhaps, if the Mojave indeed continued on to the Colorado. But unfortunately, it sinks in the desert, long before it gets there; and the enthusiastic explorer's "light-draft steamboats" would have to go paddling across a broad expanse of sand and rock, if they wanted to voyage from the Mojave to the Colorado, or vice versa! The Mojave, in fact, although draining the snow-capped San Bernardino Mountains, and a wide stretch of country there, is only another of the many strange anomalies that one meets with in[Pg 421] Southern California and Arizona. Said a ranchman in that region:

Hassayampa River

"Dis yer's a quar country, stranger, you bet! All sorts of quar things out yer. Folks chop wood with a sledge-hammer, and mow grass with a hoe. Every bush bears a thorn, and every insect has a sting. The trees is pretty nigh all cactuses. The streams haint no water, except big freshets. The rivers get littler, the furder they run down. No game but rabbits, and them's big as jackasses. Some quails, but all top-knotted, and wild as greased lightning. No frost; no dew. Nobody kums yer, unless he's runnin' away. Nobody stays, unless he has to. Everybody 'vamoses the ranch,' 'cuts stick,' 'absquatulates,' as soon as he kin raise nuff 'dust' to 'git up and git' with. You bet—ye! Sure!"

Mojave River Basin

It is due to truth to say, that our friend had just got up from the "break-bone" fever, and was still troubled with the "shakes." His mine had "petered out," and his "outfit" was about "gone up." In fact, he looked, and I have no doubt felt, slightly dismal—not to put too fine a point upon it. But I give his opinion, as he gave it to us; and the reader must take it cum grano salis—as much or little as he chooses. In truth, we have a vast region there, that as a whole is simply barren and worthless, and that will never be utilized or seriously amount to much, until the rest of the continent is well occupied and settled up. We may, of course, regret it; but that is about the truth of things, and emigrants thither soon discover it.

Camp Cady (Mojave River Valley Museum)

Beyond Camp Cady, another rude post, much like Rock Springs, we found a few ranches scattered here and there along the Mojave; but they were importing grain and hay fifty and a hundred miles, from San Bernardino and Los Angelos, for sale to passing teams and travellers, which looked[Pg 422] as if their prospects were not very flattering. There ought, however, to be some good farms there, if the Mojave were properly utilized; and doubtless this will be done soon, if it has not been already.

Cajon Pass

The Edge

At Cajon Pass, through the lofty Coast Range, you quickly run down from five thousand feet above the sea, to about one thousand feet at San Bernardino, or even less. The descent is through a wild and picturesque cañon, that almost equals in grandeur and sublimity the far-famed Echo Cañon of Utah. We camped all night near the foot of the Pass, sleeping so soundly that several mounted deserters[24] from Fort Mojave passed us unheeded, and the next morning, bright and early, we rolled into San Bernardino. Here was a well-laid out and tolerably built town, of a thousand or so inhabitants, with a newspaper, telegraph, and most modern improvements. It reminds one of Salt Lake City, and was, indeed, patterned after that gem of the mountains, being settled originally by the Mormons many years ago, when they planned a route through here to the Pacific at San Diego. We remained here but a few hours, and, as the weather was already becoming warm, started the same evening for Los Angelos, some sixty miles north, where we arrived late next morning.

Mormon Rocks

The country just now (April 26th), between Cajon Pass and Los Angelos, was beautiful and glorious beyond description. I scarcely know how to speak of it in fitting terms, but I remember well how it impressed us at the time. The Los Angelos Plains, seventy miles long by thirty wide, were one wild sea of green and yellow, pink[Pg 423] and violet—herbage and flowers everywhere. Thousands of lusty cattle and contented sheep roamed over them at will; but not one herd or flock, where there ought to be a score or hundred. The vineyards were all putting forth their leafy branches, and preparing for their purple clusters. The fields were heavy with barley and wheat. The olive and walnut orchards were clad in foliage of densest green. The orange groves were everywhere filling the air with their delicate and delicious fragrance, so exquisitely sweet and ethereal it seemed as if distilled from heaven. Ten thousand "beautiful birds of song" flitted and twittered, from bush to tree, as we drove along. On the west rolled the blue Pacific; on the east rose the noble Coast Range; and over all, like a celestial benediction, hung the California sky—a superb sapphire we never see East. The setting sun lit up the distant hills, as we gazed, and now clothed with crimson and gold—an ineffable glory of splendors—the snow-clad peaks, that towered to the north and east. Up there was the frozen zone, most of the year round; but down on the Plains, the balmy zephyrs of the tropics, and nature literally one wild scene of beauty and of glory.

Cajon Creek

The transition from the Mojave Desert, and Arizona generally, to this delightful region, was like coming into Eden—seemed like "Paradise Regained," in very truth. As we emerged from the mountains at Cajon Pass, and drove down into it, we could scarcely refrain from shouting for joy. Our animals whinnied, pricked up their ears, and, jaded as they were, trotted along with a new-found speed. Poor beasts, faithful donkeys, we had driven some of them fully fifteen hundred miles, "outside" and "inside," forth and back. Just to think of it once, plenty of good water, fresh green grass, and a moist and fragrant atmosphere once more! No more blazing sun; no more glaring sand; no more alkali streams; no more thorny mesquite and prickly cactus; no more Apaches and Hualapais, Pai-Utes and Chemehuevis; no more scanning every bush and rock by day, and listening intently to every sound by night; no more riding with rifles in our hands, no more sleeping on our arms; no more bottomless quicksands; no more fear of rattlesnakes and centipedes; no more freshets, and no more sand-storms. No! The long drag of fifteen hundred miles was over, and once more we struck hands with civilization and school-houses—touched steam-ships and telegraphs.

Lower Narrows, Cajon Pass

Verily, we had a right to sing "Out of the Wilderness," and "Home again," with infinite gusto; and it is not surprising, that with these and other jolly airs we did, indeed, make the welkin ring. Once more we had the newspapers—we hadn't seen one in a month before—that is, less than a month old—and to fair and hospitable Los Angelos, ever and truly the City of the Angels, we were welcomed as ones from the desert, if not from the dead. We had, indeed, been reported several times, as waylaid and captured by the Indians; but here we were in propriis personis, brown and hearty, though dusty and fatigued. Our good friend Banning and Don Benito Wilson were among the first to congratulate us; and their kindness and courtesy during the next three days, and until we left by steamer for San Francisco (April 30th), when shall we forget?

Across America:

OR THE GREAT WEST AND THE PACIFIC COAST.

BY JAMES F. RUSLING,

Late Brevet Brigadier-General, U. S. V.

NEW YORK: Sheldon & Company. 1874.

James F. Rusling's "Across America" is a travelogue. During rapid expansion and change in the United States, Rusling travels across the country from New York City to San Francisco. As a result of Rusling's travelogue, we gain a unique insight into American life and culture during the late 19th century. A vivid and detailed account of his experiences is provided, detailing the people he meets, the towns he passes through, and the natural landscapes he encounters. He also discusses various political and social issues along the way, such as race relations, women's rights, and the effects of industrialization. In "Across America," Rusling discusses the impact of the transcontinental railroad, completed only a few years before his journey began, and describes the wonder and excitement of this new mode of transportation and its impact on society and the economy.

Map showing route from Prescott, Az. to San Bernardino, Ca.

Map showing route from Prescott, Az. to San Bernardino, Ca.

Mourning dove

Mohave Indians - lithograph from 1856 sketch

Mesquite flower

Devil's Playground

Mojave Pottery

Mojave Indian Home

The general object of this tour, perhaps I should explain, in a word, was to examine into the condition of our various depots and posts West, and consider their[Pg v] bases and routes of supply, with a view to reducing if possible the enormous expenditures, that then everywhere prevailed there. How well or ill this was accomplished, it is not for me to say, nor is this volume the place—my Reports at the time speaking for themselves.[1]

The route thus roughly indicated was long, and in parts reputed dangerous; but for years I had cherished a desire to see something of that vast region in the sunset, and here at length was the golden opportunity. I need scarcely say, therefore, that I obeyed my orders with alacrity, and in the execution of them was absent in all about a twelvemonth. During that period, crossing the continent to San Francisco, among the Mountains, along the Pacific Coast, and thence home by the Isthmus, I travelled in all over 15,000 miles, as per accompanying Map; of which about 2,000 were by railroad, 2,000 by stage-coach, 3,000 by ambulance or on horseback, and the remainder by steamer. This book, now, is the rough record of it all, written at odd hours since, as occasion offered. Much of this journey, of course, was over the old travelled routes, so well described already by Bowles, Richardson, Nordhoff, and others. But several hundred miles of it, along and among the Rocky Mountains, a thousand or so through Utah and Idaho, and perhaps two thousand or more through Southern California and Arizona, were through regions that most overland travellers never see; and here,[Pg vi] at least, I trust something was gleaned of interest and profit to the general reader. Moreover, my official orders gave me access to points not always to be reached, and to sources of information not usually open; so that it was my duty, as well as pleasure, to see and hear as much of the Great West and the Pacific Coast everywhere, as seemed practicable in such a period.

Of course, I kept a rough diary and journal (apart from my official Reports), and retiring from the army in 1867, perhaps these should have been written out for publication long ago, if at all. But it proved no easy task to settle down again into the harness of civil life, after being six years in the army, as all "old soldiers" at least well know. I plead only this excuse for my delay—the absorption of a busy life and health not firm; and trust these notes on Western life and scenery, if lacking somewhat in immediate freshness, will yet be considered not altogether stale. The completion of the Pacific Rail road, it will be noted, made this long tour of mine, by stage-coach and ambulance, through the Great West and along the Pacific Coast, about the last, if not the last, of its kind possible; and, therefore, under all the circumstances, it has seemed not unfitting, even at this late date, to give these pages to the world.

Writing only for the general public, it will be noticed, I have tried everywhere to avoid all military and official details, as far as practicable, and to confine myself mainly to what would seem of interest, if not value, to everybody. So, too, I have aimed to bridge[Pg vii] the interval from 1866-7 to 1874 by such additional facts as appeared necessary; but without, however, modifying my own observations and experiences materially. If some persons, and some localities, are spoken of more flatteringly (or less) than usual, it is at least with truthfulness and candor, as things seemed to me. No doubt errors of fact have been committed, but these were not intended; and some of these, of course, were simply unavoidable in a book like this. So, too, as to style, no pretension whatever is made; but I claim merely an honest endeavor to convey some useful, if not interesting information currente calamo, in the readiest way possible, and a generous public will forgive much accordingly.

In brief, if what is here roughly said will lead any American to a better love of his country, or to a truer pride in it, or any foreigner to a kindlier appreciation of the Republic, verily I have my reward.

J. F. R.

Trenton, N. J., March, 15, 1874.

-FlagHistory20.jpg)

U.S. Flag - 1867-1877

Searchlight steamboat

Steamboat Explorer

1871 Ives Expedition