Southern Paiutes in Las Vegas Valley

In the southern Great Basin, the native people in protohistoric and historic times were known as Paiutes. They spoke a Numic language of the great Uto-Aztecan stock of western United States and Mexico (Madsen and Rhode 1994; Miller 1986:98-112). They were foragers with varying degrees of dependence on horticulture; they recognized territorial distinctions and had an uneasy relationship with neighboring Utes, Chemehuevis and Mohaves, but strong, mostly friendly ties to the Western Shoshone peoples to the north and in California (d’Azevedo 1986, Euler 1966, 1972; Kelly and Fowler 1986). Corn Creek was claimed by the Las Vegas Paiutes, whose territory, according to Kelly, included Pahrump and Las Vegas valleys, and part of Amargosa Valley, but Kelly excluded Las Vegas Wash and the Colorado River at the mouth of the wash. Kelly did acknowledge that there were kinship affiliations among the families of those different areas (Kelly 1934).

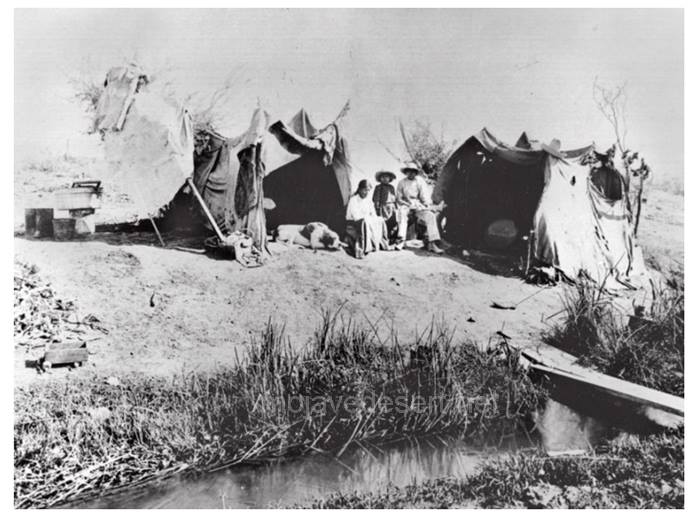

Las Vegas Springs - 1907

In southern Nevada, the cusp of the protohistoric and the historic periods is marked by the 20-year span of the Old Spanish Trail, an active channel for commerce between Santa Fe and Los Angeles between 1829 and 1848 (Hafen and Hafen 1954). This was a pack train route, blazed by New Mexican traders that linked the merchants of Santa Fe and Los Angeles to each other, and through trade, to outlets in St. Louis and Mexico City. The trail passed through southern Nevada, but the few documents that exist make little reference to southern Nevada Paiutes.

Most of the picture must be extrapolated from broadly focused histories. The information available to use in describing ethnohistoric Las Vegas Paiute culture specifically comes from reports filed after the middle of the 19th century by ethnographers, explorers, and travelers. The few details available from the very slim written sources of the early historic period contribute little to understanding the nature of Paiute life in Las Vegas Valley early in the 19th century. In fact, given the dearth of solid sources to examine, Southern Paiute life cannot be fully described for the Spanish Trail period, the first decades of contact. Recorded events that transpired later in the Historic period do make it possible, however, to make some deductions about 19th century Las Vegas Paiute life, although written descriptions are fragmentary. The few documents that exist make little reference to southern Nevada Paiutes, and they are virtually silent about the Las Vegas Valley Paiutes. They also are colored by the biases of the observers, who usually were not prepared by experience or training to understand the behavior they witnessed. Very rarely did observers understand the language of the native people they described.

The history of Spanish exploration and settlement of Mexico, Baja and Alta California has important ramifications for the native peoples of all these areas (Johns 1975, Cline 1988). Exploring parties from Mexico began to penetrate the Southwest as early as 1540, but in the Great Basin, the influence of Spanish conquest upon native culture was weak until the 18th century. Then the voracious appetite of Spanish/Mexican settlers for slave labor began to affect even the people living in areas remote from Santa Fe or Los Angeles (Warren 2001). In this portion of the Mojave Desert and adjacent southern Utah, the Ute Indians became slave traders, selling hapless Paiute captives to passing caravans of traders from New Mexico, who in turn disposed of their human cargo when they reached their intended destination in California or in New Mexico. The Southern Paiutes had no defense against the raids, perpetrated by armed and horse-mounted Utes and New Mexican traders.

The avoidance of travelers originally reported for the Southern Paiutes probably reflects the brutal encounters they experienced when raided by their powerful Ute neighbors and the foreign intruders from New Mexico. Despite the paucity of contemporary records, it is clear from post-Spanish Trail documents that the trade had strong impact on the Southern Paiutes of southern Nevada. During an 1873 visit to the area, John Wesley Powell, head of the United States Geographical and Geological Survey of the Rocky Mountain Region, recorded the refusal of the Paiutes and Chemehuevis, who lived south of Nevada’s Muddy River, to join the Utes on the Uintah Reservation in Utah. This refusal was rooted in the still fresh memory of Ute slave raids, which had ended at least a generation earlier (Powell and Ingalls 1873). Still earlier, John C. Fremont, on his epochal 1844 trip through the area, did not encounter a single live Paiute after leaving Resting Springs until he reached the Muddy River. Fremont’s path took him from west to east through territory claimed by the Southern Paiutes of the Pahrump and Las Vegas valleys. No Paiute people or evidence of camps at Las Vegas Springs and Creek were noted in his report (Fremont 1845).

Fremont’s account did contain the story of the notorious Indian raid at Resting Springs in eastern California that caused him to leave the regular Spanish Trail caravan route to render aid to the horse traders who had ventured out in advance of the main body. His story told how scouts Kit Carson and Alex Godey tracked the New Mexicans’ horses to an Indian camp, where the Indians were butchering the animals and drying the meat. The scouts killed everyone they found and retrieved the surviving horses, some of them having been slaughtered and butchered for food. Farther north along on the trail, Fremont ascended Mountain Springs Pass, where he reported finding unoccupied Indian huts, supporting Kelly’s data that include this locality as important at different times of the year, when people would be collecting pine nuts and agave, and hunting mountain sheep, deer, and small game. Fremont did not see any Paiutes, nor did he record any other camps, until he reached the Muddy River, although he spent one night in Las Vegas Valley at the Big Springs. The Mormons who settled along Las Vegas Creek did not record any irrigation ditches or gardens made by the Paiutes there, although evidence of extensive gardening was reported by Mormons in southern Utah during this time period (Fowler 1995; Roberts 2002). Still later, the Euroamerican settlers who developed ranches along Las Vegas Creek and at Kiel Spring (Figure 5.1) also failed to note in their writings any evidence of Indian agriculture. The absence of any mention of Indian gardens and ditches may have been intentional, so that the newcomers could claim the land and water without interference. Yet, the absence of early historic evidence of use by the people later called the “Las Vegas Paiutes” is difficult to reconcile with Kelly’s information, which purports to reflect native usage of water sources back to the earliest non-Indian settlements. However, given the late date at which Kelly collected her material, the specific agricultural practices reported by her informants for the springs and the creek indeed may have been historical rather than protohistoric developments. It is certainly conventional wisdom for desert environments, however, that water attracts not only flora and fauna, but people. How to explain, then, the paucity of information about Paiute use of these water sources?

Paiutes. As did the other ranchers in the valley, Kiel used Indian labor in his operations, but Indian ownership of the land was never acknowledged. Names of some of the people who worked for Kiel were remembered by the elders in 1974 (Paiute Tribal Archives) and in conversations with the elders at Corn Creek in 2002.

In part, the problem is rooted in the frenetic pace of construction in the area, which every year tears up many hundreds of acres of land in a permissive regulatory climate. Archaeology can offer the promise of reaching a better understanding of how the Paiutes used the water resources of Las Vegas Valley in the ethnohistoric period, but too often, sites are obliterated without any attempt to retrieve the cultural information contained in them. Given the rate of destruction of once-desirable human habitats, there may not be enough opportunity to do more than scratch the surface of the deep history of Southern Paiute occupation of Las Vegas Valley.

Habitable sites in Las Vegas Valley certainly were located at or near water sources. In Las Vegas Valley, where surface water was severely limited, mesquites grew in linear alignments that paralleled the creeks, in bosques that marked the occurrence of isolated springs and sand dunes, and in a vast forest that corresponded to the subsurface aquifer on the eastern side of the valley. When Seymour mapped the distribution of Patayan sites in Paradise Valley, the part of Las Vegas Valley drained by Duck Creek, he recorded their linear alignment. Seymour speculated that this distribution is evidence that the Patayans of Las Vegas Valley lived in mesquite groves and practiced agriculture much like their lower Colorado River relatives. He believes that the distribution of sites in Paradise Valley thus reveals the existence of long-gone mesquite groves (Seymour 1997: 94-108).

Las Vegas Creek was bordered on both sides by extensive mesquite growth that began within onehalf mile of the creek banks and extended in a wide band for the entire length of the flowing creek (Warren 2001). From the point where the creek trickled into the sand at the eastern side of the valley, a very large mesquite bosque extended south to the entrance of Las Vegas Wash. This expansive mesquite forest afforded ample opportunity for the Paiutes and earlier the Patayans to cultivate gardens of the sort reported for the Lower Colorado. If such plots existed, they were only rarely noticed or reported by travelers in the pre-1855 period, and not described by the Mormons during their occupation of the central valley from 1855 to 1857. In fact, the Mormons established an “Indian farm” at a spring site about one and one-half miles north of their own fort, and taught their Euroamerican agricultural practices to the Paiutes, who occupied their own camps a few miles from the Mormon compound. The Paiute camps were not sufficiently identified by Mormon diarists to enable anyone to locate them specifically.

The Indian Farm was apparently located at the spring later developed into a ranch by Conrad Kiel and his son, Edwin (Warren 2001). The Kiel Ranch, the third non-Indian ranch begun in the valley, was established at the site earlier used by Kana’gadi- and his kin (Fowler 1998). In 1875, when Kiel arrived in Las Vegas Valley, this water source, located away from Las Vegas Creek and its Euroamerican claimants, was deemed available for the taking. Paiute use of the lands and the spring was not recorded nor respected, despite the Mormon labors of 20 years earlier and the probable continuation there of farming by the Las Vegas some of the Las Vegas Paiutes who worked for Kiel are found in the Special Collection Department of the Lied Library at University of Nevada (Kiel-George Collection). At present, no identification of the people captured on glass plate negatives by Sadie Kiel George in 1900 has yet been made.

One archaeological site with prehistoric and historic components, recorded from the north end of Las Vegas Valley, suggests an ethnohistoric and historic Paiute residential pattern that also helps to explain the failure of many early diarists to record the presence of native people in the valley. Along the Eglington Escarpment, in an area that formerly featured numerous small seeps and springs, as well as isolated mesquite groves, there was both a prehistoric camp and a historic wattle and daub dwelling in a clearing surrounded by mesquites. The house was not visible from outside the mesquite grove. No evidence was found of planting of cultigens at or near the dwelling site, but the area had been badly disturbed before the survey located the feature in 1989 (White et al. 1989).

There is no historical record of Indian occupation at Corn Creek, although there is abundant archaeological evidence for it. Thus far, no diary of any historic traveler is known to include Paiute presence there. Lt. George M. Wheeler’s report of his traverse of the territory for the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers in 1869 noted a stop at Corn Creek en route to Indian Springs from Las Vegas (Wheeler 1875:21). At Corn Creek, the party found salt-grass, fair water, and no wood. At Indian Springs, the water was pure but warm, there was a little wood and scant grazing (Wheeler 1875:70). Wheeler did not mention Indians at Corn Creek.

Lt. Lockwood, sent by Wheeler to reconnoiter the area around old Potosi, southwest of Las Vegas Valley, found Paiutes in the southern Spring Mountains. Wheeler, who led a detachment along the foothills “to the northwest from the Vegas” (1875:21) noted several encampments, but not at Corn Creek. The Paiutes who were encountered lived at “rancherias,” habitation sites where the Indians raised “small crops of grain, potatoes, and many melons.” The Reconnaissance Map produced by this expedition notes rancherias located on the southeast flank of Mt. Olcott (modern Potosi), others on the valley floor in today’s Red Rock Canyon, and at Indian Springs. The natives at Indian Springs “could speak Shoshone.” From them Wheeler’s guide learned how to travel north from Indian Springs, thereby materially aiding the party on “one of the worst forced marches of the trip” (Wheeler 1875:21). He recorded Corn Creek and Indian Springs by name on the Reconnaissance Map of this expedition (Wheeler 1869).

At the time of Euroamerican incursion, the Protohistoric period in the Mojave Desert was unsettled as well in respect to native occupation and use. Early historical records report hostilities between such groups as the Mohaves and Halchidomas, the Chemehuevis and the “Desert Mojaves,” and the Southern Paiutes and the Mohaves and sometimes the Chemehuevis (Gass Daybooks 1876–1879; Kelly and Fowler 1986:378-379; Kroeber and Kroeber 1994). The Daybooks of O. D. Gass, proprietor of the Las Vegas Ranch from 1867 to 1882, contain numerous references to conflicts between Las Vegas Paiutes and “the river people” (never specifically identified). At the Big Springs in Las Vegas Valley, archaeologists have found Southern Paiute materials immediately above Anasazi remains (Warren et al. 1972), while in the south end of the valley, there is also a significant presence of Patayan ceramics. These observations lead to the hypothesis that during the Prehistoric period, Colorado River peoples from areas to the south were present for considerable lengths of time, although not resident at Las Vegas Springs (Seymour 1997). The precise nature of the interaction between the Numic peoples and the Patayans is not known for the Prehistoric and Protohistoric periods. The many similarities between these groups in the use of water and of plant and animals resources, in shared myths and dances, and in other non-material aspects of culture certainly suggest important interaction and cultural borrowing (see Fowler 1998:1.84-85; Fowler and Fowler 1971; Kelly and Fowler 1986:370).

The strong, direct, negative influence on their numbers experienced by the Southern Paiutes in response to the very powerful assaults perpetrated in the 19th century by Ute and Navajo Indians, and by Spanish and New Mexican traders, pales in comparison to the impact of the arrival of the Mormon settlers from Utah in 1855 (Jensen 1926). This date marks the beginning of permanent change in concepts of land ownership imposed by non-Indians who came to establish their own community along the life-giving stream in Las Vegas Valley. The Mormon Mission signals the end of the sway of aboriginal culture over the resources of southern Nevada. While the Mormon use of the water did not diminish the supply, the displacement of native farms and farmers that began with this settlement grew increasingly pervasive throughout the early Historic period that opened in 1855. By 1873, less than 20 years after the arrival of the Latter Day Saints in Las Vegas Valley, many Southern Paiute native inhabitants had been banished to the Moapa Reservation on the Muddy River. While a substantial number remained off the reservation, they were tolerated only as long as they provided manual labor for the ranchers who replaced them. Water was developed exclusively for irrigation of large farms and orchards planted not for subsistence, but for cash income. The Las Vegas Springs would be “improved” to produce more water for the fields of these newcomers, and the native inhabitants of the valley would find their well-established subsistence pattern diminished and eventually untenable, as the newcomers claimed these water sources for their gardens and camps.

Water was liquid gold for the settlers of Las Vegas Valley. Without it, life could not be sustained, nor could there be dwellings, farms, and cattle ranches. Without water, there could be no safe haven for travelers along the trail to California. Although, in the Spanish Trail period, the Paiutes lost people, in the Mormon Mission and Ranching period, they lost their land and their water to newcomers who did not recognize the rights of natives. From this time forward, water would become the most valuable resource to these new people who took up the land, and it would be shared only grudgingly with the people who were here first.

source: excerpts from; COYOTE NAMED THIS PLACE PAKONAPANTI - Elizabeth von Till Warren

Also see:

Southern Paiute Gardening Practices

The Paiutes used spring and creek localities in a characteristic fashion. The planting site, up to an ...

Double Loop Subsistence Strategy

The subsistence pattern reflected in the incomplete record of the late prehistoric and protohistoric ...

Shelter and Household Furniture

The lifeway of the Southern Paiute people necessitated that they be mobile and that any shelters they ...