During April, the town continued to grow. The new 180-horsepower diesel engine for the Western Lead Mine arrived and was placed on its concrete foundation near the portal of the main tunnel, next to the twelve-drill air compressor. The machines, unfortunately, were not put into immediate use, due to delays in the shipment of fuel oil. The New Roads Company, Western Lead's greatest competitor, continued to sack its high grade ore for shipment, and its new air compressor and air drills arrived. Then, on April 30th, the townsite of Leadfield was officially surveyed, and the town's plat was submitted to Inyo County officials for approval. The ambitious plat showed 1749 lots, arranged into 93 blocks. The central street was aptly named Salsberry street, while the least desirable lots, which sided upon a small ravine, were also aptly named Poverty Gulch. Significantly, all the land upon which the town was platted was upon the claims of the Western Lead Company, which donated that land to the townsite company. Although their names do not appear, it thus is obvious that the directors of the Western Lead Company were working closely with the directors of the townsite organization. The plat was approved by Inyo County officials the following month.

But in the meantime, the State of California was breathing hard upon Julian's neck. The Corporation Commission hauled a brokerage company into court for selling Western Lead stock without a state permit. The company argued that the stock which it had sold was not treasury stock of the Western Lead Mines, but was Julian's personal stock in the company. The former required a state permit, but the latter did not. Expert witnesses were called to testify, and according to the Tonopah Mining Reporter, fifteen to twenty qualified mining engineers and geologists testified that the Western Lead Mine was a quite legitimate proposition. "No testimony, except that of two engineers for the commission, was unfavorable." if the sale of stock was found to be illegal in California, the paper said, sales would merely shift to Western Lead's offices at Reno, from which California buyers could telegraph their orders.

But the continued investigations by the state of California began to hurt the sales of Western Lead stock, and another factor began to take a toll. Shortly before Julian had become involved in Leadfield, he had sold his controlling share in the Julian Petroleum Company to a former partner. His former partner shortly thereafter had engaged in a fraudulent overissue of Julian Petroleum stock, which soon caused that company to collapse. Although it appears that Julian had nothing to do with that affair, his name was firmly linked to the petroleum company in the public mind, and his credibility began to shrink. In one two-day period, the price of Western Lead dropped 175 points on the west coast trading boards, and the company never recovered from the panic which set in.

Nevertheless, Julian, the Western Lead Mine, and the numerous other mining companies involved in the Leadfield boom continued to pursue their exploration and development works. Late in May, the sixteen men working in the New Roads Mining Company opened a good strike of lead ore. At about the same time, Julian bought into that company, which gave him control of the two largest mines of Leadfield. With both the New Roads and the Western Lead companies showing steady improvement, Julian announced definite plans to construct a large milling plant at Leadfield.

As summer approached, the Leadfield boom showed no signs of peaking. More companies came into the district and began operations, including the Boundary Cone Mining Company, the Pacific Lead Mining Company, and several others. The new companies found favorable public response on the west coast stock markets at first, for the continued boom in Leadfield made it appear that the California Corporation Commission was indeed playing a sour grapes role. The district even showed signs of becoming a producer, as the New Roads Company announced that its first shipment, consisting of two or three carloads of $50 to $90 ore, would soon be ready.

The Corporation Commission, however, had other ideas, and in late June of 1926, ordered that sales of Julian's personal stock in the Western Lead mines must immediately cease on the Los Angeles stock exchange. The decision was made due to "the evidence introduced at the hearing. . . that the sale of shares of the capital stock of the Western Lead Mines Company, a Nevada corporation, in the State of California, would be unfair, unjust, and inequitable to the purchasers thereof." It is interesting to note, in light of the heavy criticism which Julian has received in later years, that the commission was careful to omit any reference to any fraudulent or illegal activities on the part of Julian.

But despite this heavy blow to the financial fortunes of Julian, developments at Leadfield proceeded. The Mining Journal a respected Arizona publication, printed a long detailed report on the Leadfield District in July, which helped to restore public confidence. "Indications are that the lead deposition in the Grapevine Mountains along the edge of Death Valley is one of the large deposits of the west and one that can be made commercially a factor in the lead production of the country." Once again, private and uninterested geologists and engineers seemed to be indirectly accusing the Corporation Commission of persecuting Julian. The mines agreed with the independent experts and continued to work. The Burr Welch Mine reported the location of new ore deposits, and the Boundary Cone Mining Company ordered and installed a new 25-horsepower hoist and headframe. The new plant had a lifting capacity of 500 tons per day, and the company increased its work force to twelve miners. The New Roads Company let a contract for the driving of another 100 feet in its main tunnel, and announced plans for early ore shipments.

At the same time, during late July, the Western Lead Mining Company and its president, C. C. Julian, brought a $350,000 damage suit against the Los Angeles Times and the California Corporation Commission, saying that the paper and the Commission had slandered Julian and the company without due cause and without sufficient evidence. The suit, however, was quickly thrown out of court for insufficient cause, "it being the duty of the corporation commission to investigate stocks and securities offered for sale in California."

During August, another new mining company, the Pacific Lead Mines No. 2, was incorporated and began work. The California Corporation Commission gave this company permission to sell its stock, 1,000,000 shares of which were offered to the public at 254 each. This decision was important, for it indicated that the Commission had finally been persuaded that Leadfield itself was a legitimate mining boom. The Commission would allow the sale of stock in Leadfield companies which were not controlled by Julian. In the meantime, the U.S. Postal Service had also decided that Leadfield was a family permanent mining camp, and on August 25th a post office was. opened in the young town.

During September and October, drilling and tunneling continued in Leadfield's mines. The incline shaft of the Boundary Cone Mine reached a depth of 200 feet, and the Pacific Lead Mines, Inc., reported lead assays of 8 percent in its ore. But in late October, two events took place which spelled the end of Leadfield. The main tunnel of the Western Lead Mine finally penetrated the ledge which the company had been tunneling towards, where its geologists had felt the best lead deposits would be. Instead of finding high-grade lead ore, the company found almost nothing. The ore assayed only 2 percent lead, far too small a percentage to mine profitably, considering the high freight costs.

This would not have been the killing blow, however, if the company had been able to regroup and look elsewhere for the elusive lead ore But at almost the same time, the California Corporation Commission dealt Julian another blow when it halted sales of stock in the Julian Merger Mines, Inc. This holding company, which Julian apparently intended to use as backup financial support for the troubled Western Lead Mine Company, had been his last financial resort. When sales of Julian Merger Mines were forbidden, Julian's hopes were crushed, and his empire fell apart. One writer later declared that Julian expended nearly $3,000,000 buying up stock after the decision was announced, desperately attempting to keep the system from collapsing. But even if this were true, which seems rather unlikely, the effort was futile. Julian was now broke, which meant that the Western Lead, the New Roads and the Leadfield Townsite companies were also broke. With the leading mining companies and the leading promoter of Leadfield out of the picture, investors in other companies quickly lost heart, and the collapse of Julian's companies had a domino effect. The other mines slowly closed, one after another, and Leadfield became a ghost town in a matter of several months. The Post Office, opened only few months before, closed in January of 1927.

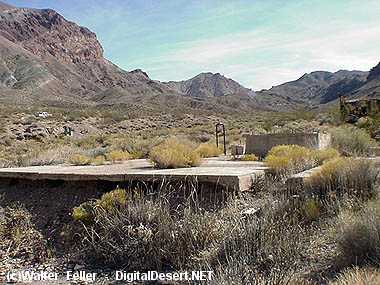

As usual, the failure of a mining district lead to a flurry of law suits. Several individuals sued the New Roads Company for back wages arid debts, and for their efforts won the dubious title to the mine. Julian appealed the decision to halt sales of Julian Merger stock to the Second District Court of Appeals of California, but lost his appeal in February of 1927. Early in the summer of that year, the Western Lead Company, with no further hope of developing its property, removed its heavy machinery and the pipe line to a mine which the company owned in Arizona. By July of 1927, the Mining Journal reported that the only work in the district was being done by seven lonely miners who were still sinking in the Burr Welch Mine, using hand tools.

Between 1927 and today, little activity has taken place in Leadfield. The National Park Service reported that sporadic prospect work was done in Titus Canyon as late as 1959, but no actual mining has been done. Julian, in the meantime, went on to the Oklahoma oil boom, where he organized the Julian Oil and Royalties Company. After several years of operation, he was indicted for using the mails to defraud investors, but he jumped bail and fled to Shanghai, China in 1933. A year later he committed suicide at the age of forty.

Miners, prospectors, promoters and newspapers usually look for a scapegoat after the failure of a mine or a mining district, and in the case of Leadfield they had a ready-made villain at hand. After Julian was indicted in Oklahoma in 1933, everyone conveniently forgot that he had never been indicted or even considered for indictment for any of his activities in Leadfield, and the story of that ghost town gradually grew into what it has become today--the story of an out-right fraud from the very beginning, instigated solely by C. C. Julian. Such an opinion was quoted at the beginning of this section.

In fairness, that interpretation of Leadfield must be revised. In the first place, it is quite obvious that there was ore at Leadfield, and that it was not put there by Julian. He in no way salted the mines, for the existence of lead ore in the district had been known as far back as the Bullfrog boom days of 1905. As pointed out above, the concensus opinion of mining engineers and geologists during the boom days was that there was lead ore in the district, and that opinion was shared by the California Corporation Commission, which allowed companies other than Julian's to sell their stock. Finally, in another conveniently forgotten report, the California Bureau of Mines and Geology reported in 1938 that the main ore-bearing ledges of Leadfield carried lead ore of five to seven percent per ton, in add to five ounces of silver per ton--enough ore to support a mining operation.

A second major point to keep in mind in that Julian did not start the Leadfield boom, and that he had plenty of help in supporting the boom once it had started. Julian was not even involved in the Western Lead Mine until several months after the boom had begun. Then, like so many other mining promoters, he hurried to get in on the ground floor. And the boom, once started, had the whole-hearted support of the citizens of Inyo County, California and Nye County, Nevada. The economies of both counties needed all the help they could set, and no one promoted the mines and attacked the interference of the California Corporation Commission with more fervor than the local newspapers. These things are quickly forgotten, however, once a boom has died. But it should be more than evident that Julian neither started the Leadfield boom nor was solely responsible for promoting it.

Finally, as a side note, it should be emphasized that the collapse of Julian's financial structure came at the worst possible time for Leadfield. When sales of Julian's various stocks were halted, his mines and others had spent thousands of dollars on the preliminary development work necessary to produce a paying mine. Miners had been hired, tunnels and shafts had been driven, machinery had been ordered, and the Titus Canyon road had been built. Then, just before the mines were ready to begin shipping ore and turning into producing companies, the collapse of Julian's finances brought about the desertion of the district. Although it seems doubtful that Leadfield had enough ore to support more than a small mining company or two, indications are that without the sudden panic of the fall of 1926, that mine or two could have survived. Harold Weight, one of the few writers who has not jumped on the blame-Julian bandwagon, gives the only satisfactory assessment of Leadfield. " . . . we will never know whether the camp, honestly financed and developed, would have made that big mine. We'll never know whether that once, Julian, as he protested, was making an honest effort to develop it."

We cannot close this section without acknowledging the one very real thing which Julian did--which was to build the Titus Canyon road. This effort, which cost an estimated $60,000, was no mean feat. The road winds up through the mountain passes for over fifteen miles from Leadfield to the Beatty highway, and climbs from an elevation of 3,400 feet at the highway to 5,200 feet through the passes and back down to 4,000 feet at Leadfield. The road was rightly considered an engineering marvel at the time, and today presents the visitor with one of the most spectacular routes in Death Valley National Park. Without Julian, that road would not have been finished, a point which awed visitors fail to realize when reading the popular literature which castigates Julian for promoting the ghost town of Leadfield.

History of LeadfieldSource - Death Valley NP: Historic Resource Study - Linda Greene