Lost City

Burrowing into the sandhills of Southern Nevada, archeologists have uncovered the homes and utensils of a thriving Indian civilization which existed 300 or 400 years before Columbus discovered America. Now the rising waters of Lake Mead are about to submerge the Lost City and remove it permanently from the field of research. But in the meantime the men of science have uncovered a wealth of interesting facts about these ancient tribesmen. The highlights of their discoveries are presented in this story by Johns Harrington, son of the archeologist in charge of the excavations.

Lost City of the Ancients to Vanish Again in Lake Mead

by Johns HarringtonDesert Magazine - December, 1937

ARROW-MAKER sat down on a boulder and looked to the east across the Valley of the Lost City where the pueblos of his people dimly were outlined in the distance.

Lizard-Digger, the Indian's lean dog. whined. He wanted to go home. They had been away for nearly a week. They had gone to Atlatl rock in the nearby Valley of Fire where his master had been praying to the Rain and Thunder Spirits, and writing picture messages to the tribal deities on the canyon walls.

Lizard-Digger had caught rabbits and other small creatures for food. Arrow- Maker had fasted to make his prayers more acceptable to the Gods. When he returned he would take part in the rituals to be held in the circular underground rooms—the kivas. Sand-paintings of clouds and lightning, and stones bearing the painted emblems of fertile crops, would surround the altars.

Arrow-Maker's people lived in onestory houses of stone and adobe, scattered along the foothills on either side of the valley for a distance of five miles. Many of the tribesmen were wealthy and the members of their clans were grouped together in apartment-like structures built around circular courts, some containing as many as 100 rooms.

Mesquite, willow, arrowweed and salt bushes covered this Nevada vallev save where the Indians had cleared the land to grow cotton, corn, beans and squash. Meandering along the length of the valley was a sluggish river, checked by an occasional brush dam built for irrigation purposes. These dams were made by driving stakes into the mud of the river bottom, then piling brush on the up-river side. Rocks weighted down the brush and the level of the water was raised enough to start small streams flowing along irrigation ditches.

Primitive Tools Used

Arrow-Maker recalled how difficult it was to rebuild the irrigation systems every spring after the winter floods had destroyed those of the previous year. The dams were easy enough to replace, but excavation work for the ditches was not so simple. It was necessary to loosen the ground with digging sticks, then transfer it laboriously with tortoise-shell scoops into large baskets to be carried away.The Indian youth and his dog resumed their journey. As they approached the pueblos the trail sometimes crossed the irrigation canals and ran through fields of maize, with bean vines clinging to the corn stalks. They passed little patches of cotton and squash along the way.

Arrow-Maker soon reached his home, the house of his mother, for among these people it was customary for the women to own the property. Arrow- Maker's father was head of one of the religious societies, and was therefore a member of the governing council of the village. The pueblo people of that period probably had no civil government— for it should be known that the scene presented here is the archeologist's concept of a civilization which existed approximately 800 A.D.

"Is there food in our house for your famished son?" asked the Indian youth as he greeted his mother. "Yes, my son. Your brother has returned from the hills with the meat of deer and mountain sheep. There will be feasting in our house for many days." Among the tribes of the Valley of the Lost City the men not only were hunters, but they built the dwelling houses, planted and watered the fields, and spun and wove the cotton. The women prepared the food and made pottery and baskets. They also dressed the skins and gathered the natural food supply from mesquite trees and the native grasses.

"Where is our father?" asked Arrow- Maker a little later when he entered the courtyard and saw his sister, Basket- Woman, grinding meal in the shade of a brush shelter within the circular enclosure. "He has gone to the salt mines where the small river joins the big one," she replied. "Others went with him as they have need of much salt. Traders from the tribes beyond the western mountains near the great water have brought elkhorns and abalone and olivella shells to exchange for our salt."

Crude was the mining of those Indians who lived in the Nevada desert three or four centuries before Columbus discovered the Americas, but effective none the less. Torches made with bark and arrowweed and fine sticks lighted the salt caverns. Notched stone hammers attached to wooden handles were used to break down the white crystals from the cavern walls.

Basket-Woman was dressed in the garb of the tribe. A dress woven of cotton and dyed a purplish color reached her knees, and around her waist was a cotton belt with designs of red and black. Her hair was tied in two knots, one on each side of her head.

The pre-historic dwellers of Lost City were short of stature and slender, with round heads and long black hair. Both men and women wore fiber sandals. The men probably picked out their sparse beards one bristle at a time, and accepted the pain with the stoicism of their race.

Arrow-Maker wore a white cotton breech clout, or sometimes a kilt. Both were held in place with a waist cord made up of many cotton strings loosely twisted together. He wore a headband similar to his sister's belt, but narrower, with a fringe on its lower edge Blankets of cotton or woven of furry strips of rabbit skin were used for additional covering during cold weather.

A daughter-in-law of the clan entered the courtyard as Arrow-Maker was talking with his sister. She carried her infant son on a cradle-board on her back. The back of the baby's head would soon show a slight deformation as a result of being lashed to the board for long intervals.

"What has happened to the house of our grandfather?" Arrow-Maker asked anxiously, for he noted that only a mound of ruins remained where the building had stood before his departure to the Valley of Fire.

"He is dead," one of the women replied. "We buried him under the floor of his dwelling. In the grave with him were placed his pet wildcat kitten and his belongings. We would have put his body in the ash dump, but it was his wish that he remain in the home he occupied for so many years."

* * *

Bit by bit, as the excavations have been carried on at Lost City, the scientists have pieced together this picture of these ancient tribesmen. Not many years after the above incidents in the life of Arrow-Maker were enacted, the people of the Lost City pueblos migrated to other sections of the Southwest. Perhaps it was due to drought, or to the raids of hostile tribes. There can be no certainty. But they vanished from the homes they had occupied for countless years, and time and the elements have conspired to make the task of reconstructing this ancient civilization very difficult indeed.

Work Started in 1924

In 1924, more than a thousand years after the Lost City had been deserted, M. R. Harrington, sponsored by the Museum of the American Indian, New York, began excavations at the site. After two years the work of the archeologists was discontinued.Then in 1929 the construction of Boulder dam was authorized—and it became known that within a few years the site of the Lost City would be submerged deep in the waters of a new lake to be formed in the basin of the Colorado river. It was evident that the excavations at Lost City must be resumed at once, or such archeological treasures as remained there would be lost to the world forever.

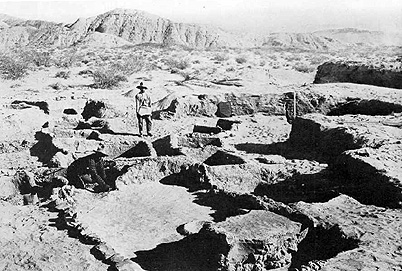

Funds were made available in 1933, and Harrington again was placed in charge, this time as the representative of the Southwest Museum of Los Angeles where he is now curator. With a crew of 32 CCC men and two experienced foremen, the work was carried on under the State Park division of the National Park service. Excavation and research continued during the winter months of 1933 and 1934 and until July, 1935, when the project was terminated for a brief interval, and then resumed again.

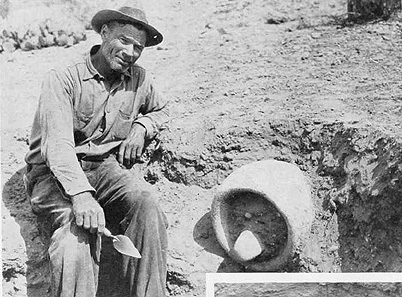

Despite the destruction wrought by time and vandals, over 100 homes have been explored. Shifting sand dunes had buried many of the old ruins, but here and there Indian ash dumps and bits of broken pottery gave clues for the sinking of test holes and the discovery of hidden structures. Some of the old dwellings were found at considerable depth, and probably there are others too deeply buried in the accumulated dust and sand ever to be brought to light.

Old Pueblo Restored

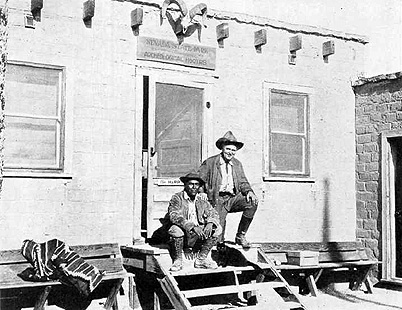

During the 1924 expedition the scientists restored one of the pueblo houses for public inspection. In the spring of 1935 a permanent museum of stone and adobe, located above the high water line of the lake, was erected near Overton, 65 miles from Las Vegas. A replica of an old adobe home was built near the museum, and a ruin of a still earlier period which was found on the higher level, was restored.Although the Southwest Museum has taken a few of the artifacts from the Lost City to complete its collection, a majority of the relics have been retained for exhibit at the Overton Museum.

Slowly the waters of Lake Mead are creeping up the desert slopes toward the site of the ancient pueblos. If Arrow- Maker and his tribesmen could return today perhaps in their superstitious Indian hearts they would rejoice at the knowledge that their ancient homes and burial grounds are soon to be protected by a barrier which even the resourceful scientist hardly could penetrate. But they would have to admit that the white man has done a very skilful job of restoring and preserving the utensils and the knowledge of their ancient civilization.

Desert Magazine - December, 1937